Editor’s note: Students, activists and other protesters have held almost daily demonstrations across Sudan since Dec. 19, 2018, calling for an end to economic hardships and mounting a sustained challenge to President Omar al-Bashir’s three decades in power.

Jan. 17: This day of protests in Sudan was a long one.

A 25-year-old medical doctor—Babiker Abdalhameed—died after being shot in his chest while caring for an injured protester at a house in the neighborhood of Burri in Khartoum. He had stepped outside to tell security forces to stop throwing tear gas inside of homes. The security forces responded by killing him, said his friend, who asked to remain anonymous.

Hundreds of protesters began to gather outside of Royal Care Hospital in Khartoum. According to reports, they chant, sing songs, and talk about the next stage of what has become one of the biggest and longest protests in Sudanese modern history.

A little after 2:30 in the morning on Friday, Jan. 18, a member of a social media group chat on Whatsapp, makes a request.

“Tents, tents, tents That’s what we need for tomorrow. Please if you can bring some tents, just bring them up to Royal Care.”

Another member wonders if the plan is to turn the streets in front of Royal Care into a Sudanese Tahir Square. “Yes that’s the plan” is the response from one of the members in the chat.

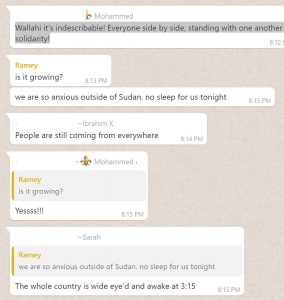

About 40 minutes later, a member of the chat writes, “Wallahi it’s indescribable! Everyone side by side, standing with one another in solidarity!“

“They are still coming from everywhere,” another member in the group chat responds.

Just a few hours later, security forces break up the gathering by lobbing cannisters of tear gas at them, sending protesters to seek refuge inside of the Royal Care Hospital.

One of the chat members checks in at 7:29 a.m.: “We are still stuck in Royal Care.” People are “stuck in the hospital now,” Ramey Dawoud, a Sudanese-American hip-hop artist, explains, because security forces soon surround the hospital and arrest anyone who leaves it.

A friend of Dr. Babiker recounts the day’s events during a phone interview and acknowledges the poor coverage of the protests in Sudan by Sudanese and foreign media. “We have been covering the story for ourselves via social media,” he says.

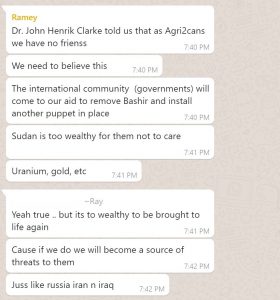

Days earlier in the group chat, Dawoud wrote, “Dr. John Henrik Clarke told us that as Africans we have no friends. We need to believe this. The international community will come to our aid to remove [Sudanese President Omar] Bashir and install another puppet in place.” Clarke is a historian and early scholar in the field of Africana studies.

The sentiment is echoed in the statements of two other members in the chat.

“The level of conspiracy against this uprising is shocking. We have no friends. Know this.”

A young Indian-Sudanese radio producer active in the protests questions the international community’s silence. He writes after a series of videos and photos documenting the actions show security forces attacking peaceful, civilian protesters.

“What’s more disturbing is the world is silent against INHUMANE treatment of civilians.”

In the early hours of the morning, activists learned of another death of a Sudanese man—Muawia Bashir Khalil Yousif. The day before, “he was keeping some protesters safe in his house and they raided the house and shot him,” said Duha El Mardi, a human rights activist based in Canada.

Dr. Babiker’s friend says a popular chant of the protest marches is “silmia, silmia,” which means “peaceably, peaceably.” He explains that it is an effort to make clear to the world that the protesters are committed to nonviolence. Instead of raising fists in the air, protesters often are seen raising up cell phones to gain clearer shots of the uprising that—because of the lack of national and international media coverage—they are largely broadcasting themselves via social media.

Since that day, protests have continued across Sudan. The government of Sudan has continued to respond by violently attacking and arresting protesters. Recently, on Feb. 1, a teacher—Ahmed Khair Ahmed Awad Elkareem—was arrested from his home in the Khashm al-Qirba region of Sudan and was returned to the family dead, with marks that appear to show he had been tortured, according to family members. His Facebook page contained posts reporting favorably on the recent protests in Sudan, expressing support for teachers’ rights, and criticizing government officials for their irresponsible use of public funds.

The recent protests are part of a long history of resistance to the Sudanese government under Bashir. The marches represent the most dynamic, energetic, and visible type of resistance that Sudanese people have engaged in over the years and in recent days.

During this latest manifestation of protest against Bashir’s government, some of the less publicized acts of resistance have been the launching of web-based print and audio news productions offering an alternative to the domestic media coverage of the protests, acts of cyber-sabotage by technically savvy members of Sudanese society, sit-ins, work strikes, and boycotts (such as those of media entities that have not accurately represented the protests in their reports).

The current protest movement in Sudan is remarkable for the apparent show of solidarity between protesters from a diversity of ethnic groups during marches in the streets. Women have been at the frontline of these protests. It also has inspired Sudanese diaspora from the United Kingdom to the United States.

Ramey Dawoud shared with us via twitter: “The diaspora has been very active in sharing information as we receive it from the ground. A number of Sudanese communities in various cities throughout the US, Europe, and Australia have organized public protests in solidarity with those in Sudan. In the US, a collective of youth have created ‘Sudanese-Americans for Non-violent Demonstrations’, an organization dedicated to raising awareness on the peaceful protests and the violent way the Sudanese government has responded to them. One challenge we face in the diaspora is the spread of false information by NISS [National Intelligence and Security Services] agents online. In the government’s internet shut down, it becomes increasingly difficult to know what’s real and what’s not. Activists have been adamant on checking reliable sources before sharing the latest news.”

"Yesterdays Sudan must go,

And make way for a new Sudan!"London 02/02/19 – Consistency is key!#SudanUprising#Sudan_Revolts #SudanProtests #موكب2فبراير#مدن_السودان_تنتفض #تسقط_بس pic.twitter.com/mhaw5Jdb8z

— ♤ (@Istageldin) February 3, 2019

Sudan’s history has been marked by racial and ethnic divisions—as was manifested in the Darfur conflict, in which Arab and non-Arab ethnic groups engaged in a racially charged armed conflict, instigated, according to reports, by the Sudanese government. The Sudanese government’s involvement in this conflict was examined by the International Criminal Court, and in 2009, Bashir was charged with crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide for his role in the widespread atrocities that occurred in Darfur against non-Arab residents.

But is the world watching?

A shorter version of this article appeared in Amsterdam News. To follow the protests, follow #SudanUprisings

If you like this article or other content on our site, support us. Here are the ways how.