By Ana María Carrano

Editor’s note: Ana María Carrano, a former journalist from Venezuela who now lives in Miami, is the executive manager of Institutional Assets and Monuments (IAM), a nonprofit organization that promotes culture and visual arts. She has found that preserving cultural heritage can empower communities.

[dropcap]L[/dropcap]ast April, when Attorney General Jeff Session announced the “zero tolerance” policy at the southwest border, a new chapter on immigration to the United States started. Adult migrants, entering the country “illegally” were prosecuted even though seeking asylum is legal without papers. Parents were separated from their children.In a tactic based on threats and fear, Trump’s administration policy wants to reduce the number of immigrants seeking asylum.

The first time I heard about kids staying alone in a detention center was in 2016. A psychologist friend of mine worked at two shelters in Florida, including the Homestead Temporary Shelter for Unaccompanied Children, until it was shut down in 2017. It reopened in 2018. My friend explained to me that the vast majority of these kids cross the border unaccompanied, believing that they are going to be sent to a detention center and, later, reunited with a relative.

Fear is the most persistent feeling among these migrant children. Most of them come from Central America (Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador) running away from the gangs and domestic violence. As many as 6 in 10 girl migrants experience sexual abuse during the journey, according to Amnesty International. Some spend about a month in the desert before crossing the border. A horrific experience. And yet they continue to come.

Although more than half of 2,551 migrant children have been reunited with their parents, after Judge Dana Sabraw ordered a July 26 deadline for reunification, more than than 400 families still are separated. Some cases haven’t been resolved because the parents have criminal records, or a different relative has released the kids.

From my perspective, immigration has three essential areas of debate:

- Current immigration policy needs reform. The U.S. government should explore better alternatives to handle immigration. They need to, at a minimum, find ways to integrate or legalize the status of long-term undocumented immigrants without criminal records.

- This is not a one-sided problem. Most immigration has its origins in impoverished and violent environments. It’s time to think harder about how to work in collaboration with those countries to help them find ways to overcome the crisis and offer better opportunities for their citizens.

- The most important lesson learned during this “zero-tolerance” policy is linked to human rights. The treatment received by immigrants in all stages of their process always should be respectful. That shouldn’t even be a discussion. Republican Sen. Rob Portman said in April, “These kids, regardless of their immigration status, deserve to be treated properly, not abused or trafficked when talking about a case of eight minors from Guatemala forced by traffickers to work 12 hours a day in Ohio egg farms. “This is all about accountability.”

An undocumented immigrant does not deserve to be abused or separated from their parents. We need to ask for more compassion when approaching these situations.

Aren’t We All Immigrants?

[dropcap]I [/dropcap]come from a migrant family that has moved away from tough situations over generations. My paternal grandparents left Italy after World War II and moved in 1948 with their three kids to Venezuela, a country they had never visited. They were running away from the starvation after the war. My Aunt Laura still remembers how my grandma cooked bread filled with oakum (loose fiber from old rope) to fill the stomach. Broke and hungry, the Carrano family started over and eventually became economically stable.

My great-grandfather on my mom’s side was a doctor who fled Venezuela while running away from the dictator Juan Vicente Gómez, who governed the country from 1908 to 1935. He moved to New York with his family. During the 1930s, my grandmother, María Luisa Tolosa, met my grandfather, Mario Sauma, when they worked in a clothing factory. Mario also was an immigrant: born in Costa Rica from parents who had moved from Lebanon.

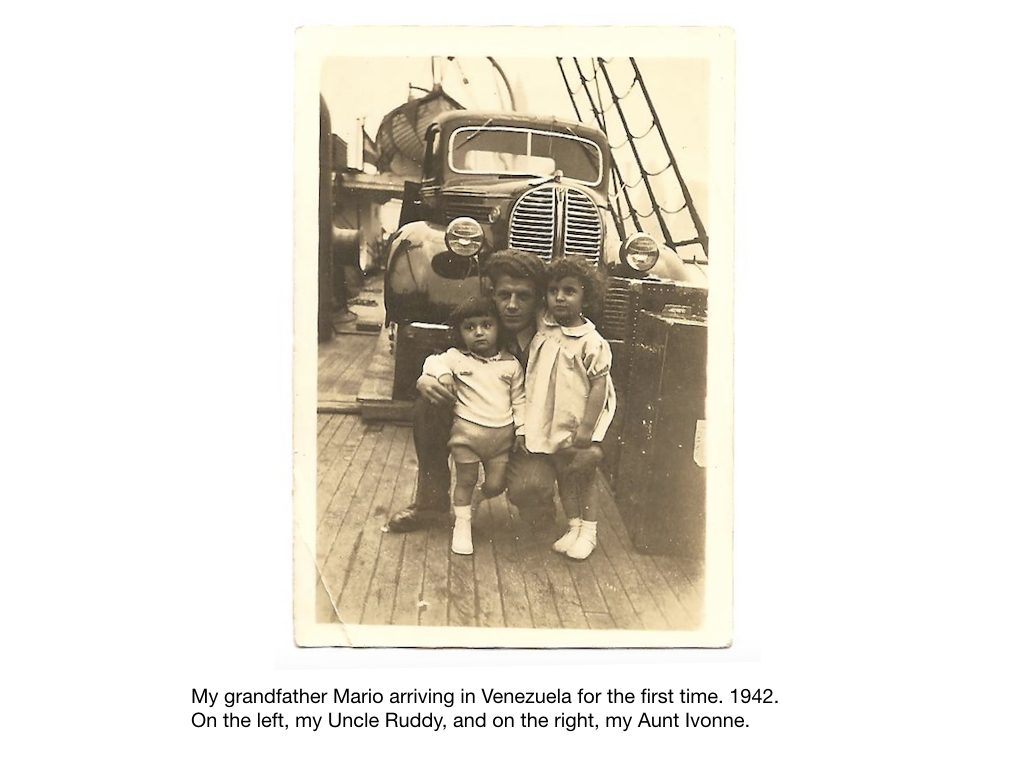

María Luisa and Mario struggled hard during the Great Depression. Some years later, they decided to emigrate from the U.S. Already with two kids and pregnant with my mom, María Luisa thought that going back to Venezuela was an option. The dictatorship had ended by that time, and she had family there. Again, it was a big move motivated by the idea of finding better opportunities. And so it was.

Many decades later, it was my turn. I moved to the U.S. from Venezuela in August 2013. I wasn’t running away from the country. I had been selected to be a John S. Knight Fellow at Stanford University, a 10-month-program focused on journalism and innovation.

Although my immigration transition went smooth—I got a permanent status that is granted based on merits—I’ve seen countless Venezuelans coming to the U.S. in desperation, doing any job and seeking asylum.

They are just running away from crime and dictatorship. The Maduro government is cruel. Protesters have been killed in demonstrations. Most news media, including the one I worked for, the government acquired directly or indirectly. Many of my fellow journalists were fired and threatened. The economic inefficiency led to severe hyperinflation that is a nightmare, with an annual inflation rate of 1,000,000 percent. People I know with full-time jobs don’t make enough to eat every day. Water and power outages can last three continuous days in some cities.

The impunity rate is over 98 percent. The judicial system is corrupt and politicized, and security forces are not accountable. This leads to an extreme level of crime. The country has a rate of 89 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants, according to the Venezuelan Observatory of Violence (OVV). In 2017, the Mexican think tank Citizen’s Council for Public Security and Criminal Justice listed Caracas as the most dangerous city in the world.

Long story short: Almost every Venezuelan has at least one relative or close friend who has been kidnapped or murdered.

Preserve the Past to Power the Future

[dropcap]C[/dropcap]ultural heritage offers a connection to our history, a sense of belonging to a community. It gathers symbols of a culture. It implies a shared bond.Cultural symbols can help to rebuild societies.

In a country deeply divided along ideological lines, art and other cultural manifestations can be an area for dialogue and reunification. However, some monuments can’t do that because their meanings were redefined by political perspectives or they were created by artists with radical political positions.

Information on IAM

In 2014, I started working with philanthropist Nina Fuentes and the museologist Milagros González. Together, we created Institutional Assets and Monuments, an organization to work on the promotion and preservation of cultural heritage, with particular emphasis on heritage at risk. We have worked in Venezuela and are expanding to Miami and countries in the Caribbean.

What do we do? We engage communities and help them grow by understanding their memory and assessing their cultural heritage.

In partnership with the organization The Arc/k Project, a nonprofit organization that specializes in digitally preserving cultural heritage, we started working on photogrammetry, a technique that helps you build 3-D models of objects. Over 50 trained volunteers in a half-dozen Venezuelan cities are now photographing more than 250 artifacts and monuments in the country. Some of them are UNESCO World Heritage sites. With this content, we are producing a library of 3-D models of objects of cultural significance.

In Miami, the threats for the preservation of heritage are different. The city is growing fast. Since most of the residents are foreign-born (59 percent), we are developing a project to connect residents with the local symbols.

We believe people can give a voice to their monuments and offer a more profound perspective on immigration.

Our Community Based News Room publishes the stories of people impacted by law and policy. Do you have a story to tell? Please contact us at CBNR. To support our Community Based News Room, please donate here.