ShaCorrie Tunkara called me crying. I was on my way to the Northwest Detention Center (NWDC) in Tacoma, one of the biggest immigration detention centers on the West Coast and could hardly understand what she was saying.

They want to deport him now,” she cried, almost yelling, desperate to keep her husband and father of their two children in the country.

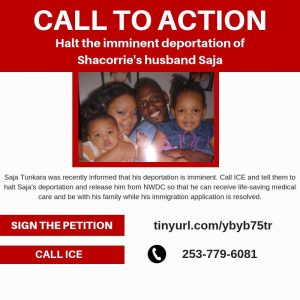

I met ShaCorrie via text in early 2018, the fourth year of our group, La Resistencia (formerly known as NWDC Resistance), which supports people in detention and their hunger strikes to expose the inhuman detention conditions. She texted me saying her husband was detained at NWDC, and he needed a surgery that Immigration Customs Enforcement (ICE) kept delaying for months. It took several weeks for ShaCorrie and me to meet in person, but from the beginning, I knew she would do anything possible to keep her husband, Saja Tunkara, a native of Sierra Leone, here in the United States.

Saja was detained in early January 2018. ICE was aware of his medical condition —a tumor growing in the left side of his neck—and that surgery already was scheduled for mid-January. But ICE decided to detain him anyway, and the surgery was canceled.

The surgery didn’t happen until mid-April 2018. ShaCorrie didn’t know Saja was being sent to the hospital, and it took several days for her to locate her husband. No one informed her of Saja’s whereabouts during that time. After the surgery, there was no follow-up on physical therapy as prescribed. Saja was told he needed 12 therapy sessions since the surgery would impact his arm mobility, and it did, but only five sessions were given. Saja’s tumors kept growing and ended up affecting his vision as well.

We often hear these stories from people detained. We also hear that ICE claims people detained will receive the best care possible while in NWDC. We have found that claim to be a lie.

The same year we were contacted by ShaCorrie,, Ricardo Rivas Martinez called us. He was another person detained and needed surgery to remove a hernia. The hernia was so big he had to hold it with both arms. He also needed a support belt and therapy for an injured hand. Both of his medical conditions were due to a workplace injury with a landscaping company. However, he was not receiving any medical care in detention. Ricardo told us about other people with medical conditions not receiving care.

Our job is to expose these human rights violations. We work with detained people, their families and sometimes elected officials to pressure ICE to release people in detention or at least provide them the urgent medical care they require.

So we sprung into action and did what we do best. Demonstration after demonstration, ShaCorrie came to speak. She attended every meeting with elected officials and city hall hearing to discuss her husband’s case. We began a campaign demanding Saja and everyone with medical emergencies to be released. And finally, a media exposé was published with Saja as the main featured story, along with many others, including Ricardo.

A couple of days after this exposé was published, ShaCorrie received a call saying Saja would be deported. That’s the day ShaCorrie called me on my way to Tacoma to let us know Sajawas being deported. And that was the first time I heard ShaCorrie cry over the phone.

In less than three weeks after the story’s publication, Saja was deported. Ricardo was deported on Oct. 8. For us, the message was clear:These deportations were retaliation against brave detained people going public with the human rights violations and medical neglect they face at NWDC at the hands of ICE.

Many times before, detained people have suffered consequences for speaking up and organizing against their jailers. Hunger strikers have been sent to solitary confinement This action triggering a lawsuit that is still pending. But the most horrible consequence we have seen in NWDC for a hunger striker was the death of Amar Mergansana in November.

All efforts to stop Saja’s deportation switched to keep him alive in Gambia, where he was deported. No surgery is available in that country to take care of the tumors that keep growing in his neck. Ricardo was able to contact us as he made it to El Salvador in excruciating pain and with no hope of getting medical care due to lack of money.

While Saja’s deportation flight happened via a commercial flight, Ricardo’s flight to El Salvador began at King County Airport in Seattle via a private company that has a contract with ICE to deport people. The flight to El Salvador had six layovers, including a night stop. Ricardo’s deportation trip started on Oct. 9 in Seattle at 9 a.m., and after three stops, he said all the people in the plane were sent to a detention center “inside an airport” to spend the night. The deportation flight resumed the next morning at 5:30 a.m. with three more stops, and arrived on Oct. 10 at 4 p.m. in El Salvador.

The whole time Ricardo was on the planes, he was handcuffed on his feet, waist and hands. He kept asking for relief from the tight handcuffs, which left bruises,but no one paid attention.The only words anyone spoke to him during the transportation were insults and derogatory names.

“In the detention center, guards treat us badly, and then bad treatment continues right before, during and after the flights,” Ricardo told me over the phone. “It affects us emotionally. I can’t sleep anymore. Not only because due to my hernia, but because of the emotional toll it takes on you.”

This is a common story we hear from people being deported, They are humiliated and mistreated even in the last stages of the deportation process.

In Ricardo’s current situation, the lack of medical care impacts his family and everyday activities.

“I need help to get up from the floor where I sleep, and I need my daughter’s help all the time,” Ricardo said. “I can’t sit correctly. I have to push the hernia in to be able to sit. It hurts when I push it in.”

Ricardo used to be a taxi driver. Now, he’s not able to work, so he can’t pay for doctor’s visits or medicine.

“You should worry when the hernia doesn’t go in anymore,” Ricardo remembered a doctor told him while he was detained.

Wendy Mironov, a nurse practitioner in Seattle, has visited people detained at NWDC. She knows that lack of medical care at that facility could have worsened Ricardo’s medical condition.

“Ricardo’s hernia caused him daily pain and physical limitation,” Wendy said. “Surgery is the treatment for a highly symptomatic hernia such as this. By denying him surgery, the detention center both caused him to suffer daily physical symptoms, and put him at risk on a daily basis for emergency complications such as hernia strangulation or bowel obstructions.”

Saja today is in Gambia, and ShaCorrie is trying to get enough money to pay for his trip to the United Kingdom, the only place nearby where he could get the surgery he requires. Saja has lost 50 pounds and requires a wheelchair to move around. He continues having problems with his right arm mobility and eyesight. As the tumors keep growing, he has now a blood clot in his chest and two lumps in his throat that make it difficult to speak. Iff all of that isn’t enough, he also suffers from a swollen prostate.

Wendy had access to Saja’s medical records and found his treatment alarming.,

“Saja’s medical records include multiple records of chest pain, malaise, and weakness,” she said. “He was treated with heartburn medication, but they never resolved his symptoms. It’s not shocking to learn that with these symptoms, he was diagnosed with a pulmonary embolism when he finally was able to get some medical attention after being deported. A pulmonary embolism is a life-threatening blood clot in the lungs. It leads to death in about 30 percent of patients if untreated, and can quickly cause shock and organ failure. It’s horrific to think that this life-threatening medical issue was likely going on in detention, that his complaints were not fully addressed.”

Mironov also is familiar with other medical neglect stories and helped families of those detained understand medical records, when those are given to detained people.

“I’ve regularly read in medical records something that is very striking, ‘Due to the unpredictable nature of the immigration process including length of detention stay, the purpose of psychological intervention will be the stabilization of presenting symptoms, acute crisis intervention, and brief supportive/solution-focused therapy,’ ” she said. “This focus on acute symptoms appears to be much the same philosophy for general medical care as well. Basic health care to maintain and promote health is scarce.”

Ongoing complaints about lack of medical care and terrible, low-quality food (that in some instances has maggots), top the list of grievances and demands during hunger strikes. These two main complaints aggravate or cause some of the medical complaints at NWDC. “It’s very unclear how and under what circumstances people in detention are able to access specialty care,” Wendy added. “Often people who are in detention report going again and again to the health services for chronic conditions and receiving the same cream over and over again with no change in result and no higher level of care.”

Alejandra Gonza, an international human rights attorney and the director of the International Human Rights Clinic at the University of Washington, has reached out to the United Nations (UN) to get support for Saja. In March, Gonza filed a letter on Saja’s behalf that would make Gambia responsible for his medical care. In the letter to the UN Universal Periodic Review, Gonza explained that her legal clinic has documented several cases of medical neglect at NWDC, including Saja’s, and the conditions the U.S. government has created in the past few years to deport more people, regardless of their community ties or long standing in their communities.

“In that context, unfair deportation of people suffering health problems to countries they haven’t lived for years, creates obligations to receiving countries to protect and respect the rights of returnees, and address the situation with humanity,” the letter read. “Particularly, Gambia has the obligation to provide support to deportees to overcome individual challenges, and answer to specific needs, addressing vulnerabilities and protecting and respecting their human rights.”

In our immigration fight, a universal truth gets lost: Immigrants are human beings. They have basic human rights and families who love them. Dehumanizing these loved ones makes the fight to save them even harder.

“I’ve learned how difficult it is to gather all the documents required to prove the urgent need for Saja’s medical care,” said ShaCorrie, describing her struggle to get medical care in Gambia. At the same time, ShaCorrie continues pushing for the application she submitted to ICE as a U.S. citizen in 2018 to be approved, so Saja can come back home to his family.

Since arriving in El Salvador Ricardo communicates with us via his daughter, Kenia Acevedo, using her Facebook profile.

“We needed to be in touch with La Resistencia, and being so far, the only affordable way to do so was through social media,” Kenia said. “We are thankful to be able to follow up with my dad’s case worker through La Resistencia, and although my dad is still suffering and needs medical attention, we hope he will get better soon.”

La Resistencia was able to put them in touch with the caseworker at the Department of Labor and Industries in Washington state, where his work injury claim continues. The family hopes the department pays for whatever medical care can be provided in El Salvador..

These moments provide strength. As we continue working to expose inhumane detention conditions and build enough support to shut down NWDC, we find ourselves with connections to people in countries where I never imagined we’d have them.

ShaCorrie decided to remain part of our group while she fights for the well-being of her life’s partner, Saja Tunkara, and fight for everyone detained.

“No one should go through what my family has gone through. No matter what nationality you are, skin color, or background,” ShaCorrie said. Saja should be home with us, and we should be able to ensure he receives the medical care he urgently needs.When your loved one is deported, the story doesn’t end there.”

To support Saja, please donate here. To support La Resistencia, follow them on social media @laresistencianw, @nwdcresistance and donate via their website.

Our Community Based News Room publishes the stories of people impacted by law and policy. Do you have a story to tell? Please contact us at CBNR. To support our Community Based News Room, please donate here.