Pamphlet to Farmers from ABSP-II funded by USAID

Imagine if people living in the United States could petition the courts on the grounds that they have a constitutional right to their individual health and a balanced and healthy ecology. Imagine if companies were required to demonstrate with full scientific certainty that any product entering into the market for human consumption is free from harmful consequences or food produced would not have a detrimental environmental and ecological impact. Further, imagine if courts would employ a legal doctrine called “precautionary principle” in determining whether to permit the introduction of new scientific technology, especially biotechnology that could potentially impact the environment in ways that are irreversible. The result would be that our legal landscape for those concerned about health issues and our environment would dramatically change, and our executive and judicial bodies would act with greater caution in assessing the impact of new biotechnologies.

Of course we know that not to be the law in the United States, but such a constitutional right does exist in the Philippines. The principle of protecting our biodiversity is not the law in United States because it has not signed the Convention on Biodiversity, and the supplemental Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety which sets forth the precautionary principle. This Filipino constitutional right was discussed while reviewing a petition to enjoin the field trials of a genetically modified organism (“GMO”) eggplant. In a decision dated May 13, 2013, the Court of the Appeals in the Philippines reviewed a petition to halt field trials of the GMO eggplant (also referred to as BT Brinjal) because the public and private respondents could not show with scientific certainty that such field trials would not cause damage to the ecology. BT Brinjal is a genetically modified eggplant carrying a transgene that is said to be resistant to two insects that infect an eggplant and decreases its yield. While the court locates the right in the nation’s constitution, it goes so far as to reason by highlighting another case that such right to a balanced ecology is rooted in natural law, and predates the formation of the state. The court quotes, Opasa v. Factoran:

“While the right to a balanced and healthful ecology is to be found under the Declaration of Principles and State Policies and not under the Bill of Rights, it does not follow that it is less important than any of the civil and political rights enumerated in the latter. Such a right belongs to a different category of rights altogether for it concerns nothing less than self-preservation and self-perpetuation – aptly and fittingly stressed by the petitioners – the advancement of which may be said to predate all governments and constitutions. As a matter of fact, these basic rights need not even be written in the constitution for they are assumed to exist from the inception of human kind. If they are now explicitly mentioned in the fundamental charter, it is because of the well-founded fear of its framers that unless the rights to a balanced and healthful ecology and to health are not mandated as state policies by the Constitution itself, thereby highlighting their continuing importance and imposing upon the state a solemn obligation to preserve the first and protect and advance the second, the day would not be too far when all else would be lost not only for the present generation but also for those to come – generations which stand to inherit nothing but parched earth incapable of sustaining life.”

The decision holds the right to a balanced and healthy ecology, which also includes an individual’s right to health, as an inalienable right. Placing the right to balanced and healthy ecology alongside other inalienable rights such as the right to a family and life, and liberty, places it in equal position, and therefore cannot be abrogated by the state. Such a legal position makes common sense because you cannot separate one’s right to life by not including within it a right to health or a healthy environment. One can further argue that the right to life presupposes that the state also is committed to protect the conditions of life which includes environment, ecology, biodiversity and indigenous knowledge practices.

The Filipino decision reveals that we need not assert a right to a balanced and healthy ecology, since it is already part of natural law, and in the United States would then be included under Fourteenth Amendment’s protection of life. Inclusion of an explicit right to a balanced and healthy ecology in national constitutions can achieve the same result and hold the countries obligated to investigate the health and environmental impact of gmo crops. Otherwise, States could not be held accountable to conduct independent scientific research to assess the health and safety claims of biotech companies. In the absence of state regulation, research is funded and regulated by the same biotech companies that profit from the promotion of gmo crops. In the United States, Doug Gurian-Sherman with the Union of Concerned Scientists explain that companies like Monsanto or Syngenta do not provide scientists with seeds or set highly restrictive conditions for research such that an accurate picture of the risk or benefits of GMO crops is unable to be determined.

While the Philippine decision seems to be the most robust declaration of the right to health and a balanced ecology, there are 90 other constitutions that have such a right in some form except the U.S. If such a right existed to health or a balanced ecology, GMO labeling bills in the United States would probably not face such an uphill legislative battle. The failure to pass GMO labeling laws would then be a deprivation of a person’s right to life without due process of law. The burden would be on the companies to show that the GMO product does not cause any harm to one’s health or environment.

In the case of the GMO eggplant field trials, in 2010, India ordered a moratorium, citing safety concerns after massive mobilization and activism. India’s outcome on the GMO eggplant reveals that the existence of a constitutional right would have produced a stronger legal outcome in that instead of an administrative order, there would have been a judicial binding decision articulating a standard by which companies must show whether GMO crops impact public health. Unlike the Filipino decision that provided a more meaningful interpretation of the precautionary principle, in India, the administrative order does not articulate a legal standard for that principle.

Despite these two decisions calling into serious question the safety of the GMO eggplant, one judicial and the other administrative, it is therefore shocking that no such legislative action has been taken in Bangladesh where the field trials continue. Activists question the reasons why Bangladesh has moved so swiftly ahead with the approval of GMO eggplant given such serious concerns from India and the Philippines. Further, although the Cartegena Protocol on Biosafety requires states to pass biosafety regulations, Bangladesh has not done so. In the absence of such safety regulations, the introduction of GMO eggplant in Bangladesh would be disastrous.

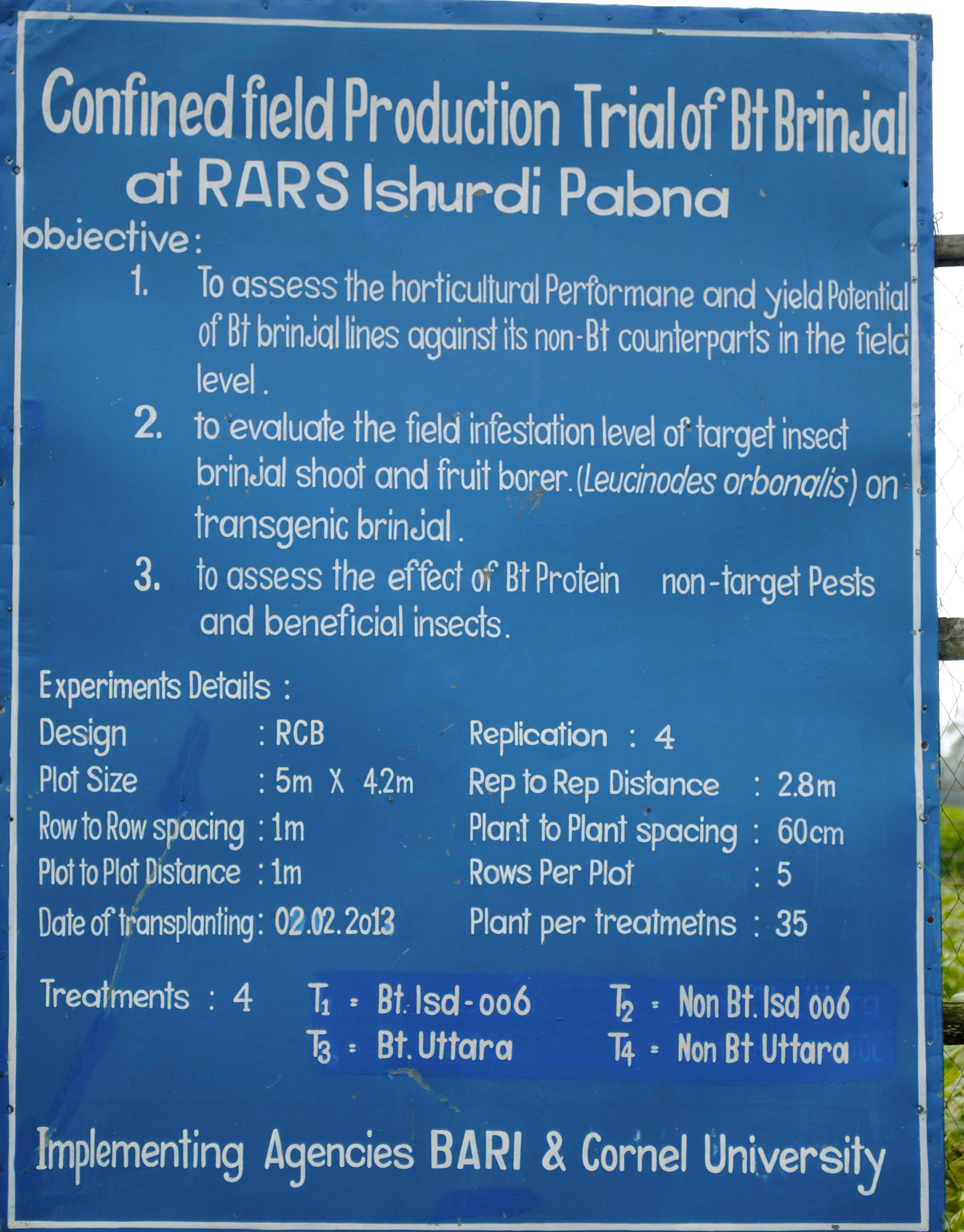

BARI Sign on BT Brinjal Field Trials in Ishwardi, Bangladesh

Media accounts show that the Bangladesh government has already petitioned for the approval of the eggplant and it will be released in the next few months. Yet, scientists have not made public or available any information on the impact that the eggplant will have on public health and the environment. My meeting with scientists at the regional level in Ishwardi’s Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute (BARI) on July 3, 2013, revealed that their research did not include any study of the public health or environmental impact of BT brinjal. Scientists were given limited research mandates by US research partners – Cornell University and USAID – to look solely at pest infestations. They were not funded or mandated to do a broader environmental or public health impact. This always raises genuine ethical and professional concerns for local scientists who are knowledgeable about local biodiversity issues, connected more directly to farmers, and would like to produce a more comprehensive study on GMO crops before its released.

However, scientists I spoke with explained that they are unable to conduct an environmental impact report due to funding or research restrictions or because these policy decisions are made at a higher governmental level. This confirms concerns by the Union of Concerned Scientists that restricted and biased research prevents a full understanding of the health impact of GMO crops.

Here, it is worth noting that while BARI is working with Cornell University, it is documented that Monsanto who stands to benefit from any patent of GMO eggplant, has generously funded Cornell’s agricultural and life sciences department. USAID is also a key partner in the promotion of biotechnology through the Agricultural Biotechnology Support Project II South Asia (ABSP-II). On their website, you can see the USAID logo and the caption: From the American People. Speaking to activists here in Bangladesh, GMO crops are not a gift they would like from the American people. As US citizens, and other concerned global citizens, we should fight against our governmental agency’s and elite academic institutions’ promotion of GMO crops abroad in countries like Bangladesh because it undermines our own efforts for a safe and healthy food and environment. Given such a narrow focus of the research and the field trials, and huge incentive for biased research, it would be impossible to make any accurate assessment of the public health and environmental impact of GMO crops.

Further, in the absence of complete and independent research, it seems unconscionable to allow the GMO eggplant to be released for public consumption in Bangladesh or anywhere. In addition, it has not been shown how the GMO eggplant will impact other eggplant varieties, and the overall biodiversity of the environment; this showing is a mandate of the Convention on Biodiversity. Without comprehensive information and with some level of scientific certainty, the release of the GMO eggplant can be devastating, and even worse, irreversible. Applying the precautionary principle here, based on international environmental law, the Bangladesh Ministry of Agriculture should have a moratorium on the trials, and advocates should push for a constitutional right to health and a balanced ecology. At present, there is no such explicit right, but such a right has been found to exist under the constitutional protection of life. However, it would be effective if such a right was clearly established in Bangladesh so that in the future any GMO crops would be subject to a clear standard whereby the party seeking to release GMO crops would have to show that there would be no environmental or health impacts.

An explicit constitutional right to health and a healthy ecology can minimize the enormous influence biotech companies would have in public policy decisions both in Asia and in the US. By working with activists in Bangladesh, and in South Asia, we can push for a robust right to health, and a balanced ecology. And, it may as well start with the eggplant.

Photo by BBC.Co.UK

In terms of acreage and production,eggplant is the most important vegetable in Bangladesh.It is also the most common and favorite vegetable of the people across rank and file .It is pleasing to remember that eggplant is a native of this land .In spite of multinational aggression on our gene pool still there are diversity of forms in shape ,size, color and taste of eggplant . Since Bangladesh is one of the primary centers of origin of eggplant,we thus hold the responsibility to save the genetic variability of the plant

according to our ratification of the CBD in 1994.We must resist any act of tempering the genome of eggplant.

The article,Eggplant and the Constitutional Right to Health and Balanced Ecology is definitely a bold and convincing argument for public perception and legal foundation dedicated for resisting childish act of tempering genetic base of eggplant and such other life forms. The author deserves best of appreciations .