It’s time to end state-sanctioned violence on our streets and inside correctional facilities.

By Shandre Delaney

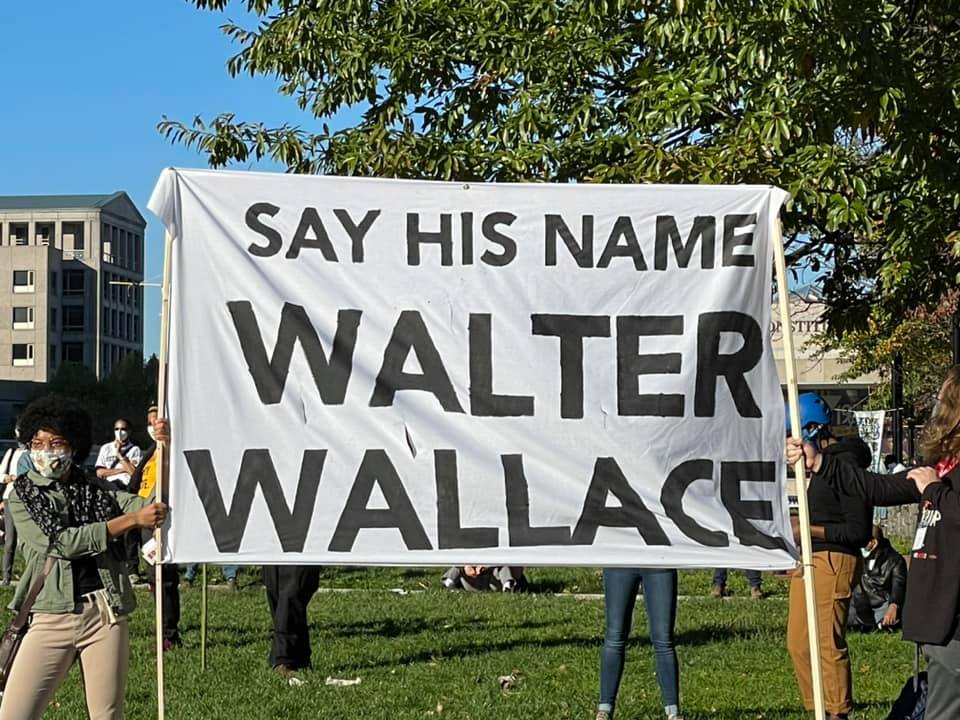

On May 25, 2020, a cry reached far and wide. It was George Floyd calling for his mother. His voice and the fear in his face were felt deep within our hearts. Protesters still fresh in the streets for Breonna Taylor witnessed another human being taking his last breath in front of the world. His death reignited the movement.

What mainstream media labels rioting and uprising is a roar from those who are tired of watching people die at the hands of law enforcement with impunity and then being asked to be “peaceful” protesters. Because of technology, state-sanctioned violence by police is now in full view of the public daily. Just like on the outside, protest is happening inside prisons.

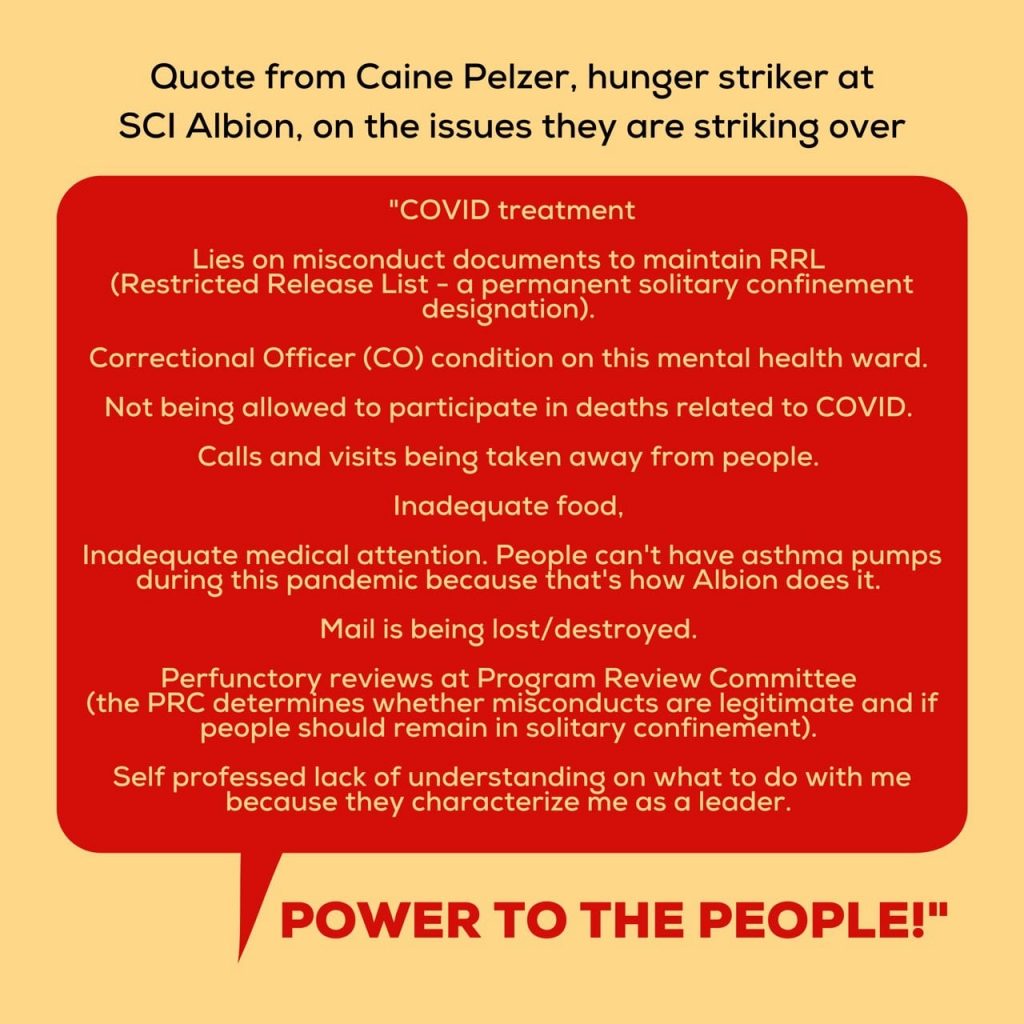

More recently, prisoners are protesting because they are not protected from COVID-19. They are also being put in solitary and lockdown with no communication, which causes undue stress. Like those on the streets, prisoners have been protesting racism and brutality at the hands of guards with impunity for years. Hunger strikes, uprisings and peaceful protest are as common on the inside as they are in the streets. Prisons have recorded their violent interactions with prisoners long before social media, but those videos rarely reach the public eye. But in recent times, through cell phone videos leaked by prisoners to the public, we can now witness how brutality continues within the prisons.

In an email from Thomas Woods, a friend on the inside, after witnessing the George Floyd killing on the news, he said, “The issue ain’t just out there with the police, it’s even worse in here with the racism. Something needs to be done as they have their feet on our necks, too.”

I Can’t Breathe

I can’t breathe. So many people who die by law enforcement say these three words. In 2012, they were the last words heard on the block from John “J-Roc” Carter in his solitary cell at SCI (State Correctional Institution) Rockview in Pennsylvania. According to witness accounts, Carter was killed during a cell extraction when guards sprayed his cell with an excessive amount of pepper spray after he protested being denied food. They sprayed so much that they “turn[ed] his cell into a gas chamber,” one prisoner reported, and the whole tier was choking. The guards had on masks when they beat and tased him while he was gasping for air. Then he was dragged off the block unresponsive and taken to a hospital where he was pronounced dead. The prisoners say a cover-up began immediately.

Even though Carter suffocated from the pepper spray, his death was listed as sudden cardiac arrest. No one was ever charged. The state police “investigated,” but never questioned any prisoners who were witnesses. The police findings were inconclusive. The prison’s investigation of itself turned out the same result. Data from a Reuters report shows how prisons are concealing state-sanctioned violence. Mortality rates in U.S. jails rose 35 percent from 2008 to 2019. Like in the case of John Carter, it is apparent that deaths at the hands of guards in prisons and jails are classified to conceal the cause.

A common theme in law enforcement-initiated assault is the perception that someone is resisting. Anything can be viewed as resistance and used as reasoning to brutalize or kill someone.

In prisons, they use resistance as justification to abuse and murder prisoners. In the prison videos I’ve seen, guards scream “stop resisting” before they start to beat a prisoner and continue to yell it while assaulting them. From the position of the camera, you cannot view the prisoner. You only hear the guards, so you believe that person is resisting. In the video of my son Carrington Keys, a solitary confinement survivor, who was peacefully protesting in prison, you can hear him screaming, “I am not resisting!”

The Militarization of Law Enforcement

The United States has a deep connection to war and the military. Weapons of war are as much a part of the economy as day-to-day consumer products. The U.S. government makes about $55 billion per year from the sales of defense equipment to foreign allies and partners in the name of regional security. Since 1997, when President Bill Clinton started the 1033 program, $7 billion worth of military equipment has been distributed through the Defense Department to over 8,000 police departments in the U.S. We have witnessed the use of those weapons against citizens escalating, especially against protesters, whether they are peaceful or not.

Tear gas is one of the most used tactics against protesters. This chemical irritant causes burning and tearing of the eyes, coughing, difficulty breathing, and irritation to the skin. Tear gas is banned in international warfare, but it is still used on civilians in many countries, and over 100 U.S. cities have tear-gassed protesters since May 2020.

Like police forces, prisons use military-grade tear gas and military-style weapons to punish unarmed and nonviolent people. The practice has been going on for a long time. Prisons are equipped with tasers, shock shields, and batons, and, in some states, even guns.

People in solitary confinement face some of the most torturous practices. At least 61,000 people are in solitary confinement in U.S. prisons, and the number could be higher since there is little official data on the use of solitary confinement. The most recent authoritative source of information was a 2005 Bureau of Justice Statistics census, which showed 81,722 people in “restricted housing” in state and federal prisons, according to Solitary Watch.

I spoke to a long-term prisoner, Michael Rivera, at SCI Benner in Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, about what he has witnessed inside prisons. Over the past five years, he said he has seen an increase in the use of pepper spray and electric shock shields within the restrictive housing unit (RHU), and vulnerable people are subjected to longer periods of solitary confinement than before. He added that RHU staff often will deny inmates clothes, personal property, mattresses, bedding and any cell contents for arbitrary reasons.

“If you resist in any way, they dress up in riot-style uniforms, wearing helmets and face coverings, while brandishing batons and a shock shield, and six to eight officers enter your cell and remove you by force,” explained Rivera. “That has a chilling effect on a lot of prisoners who struggle to cope with the psychological torture of sensory deprivation. It’s almost like a quasi-SWAT team is raiding your cell, for something as minor as refusing to take your psychotropic medications or turning your light on during count time.

“Recently, I, myself, was unnecessarily exposed to pepper spray while using the telephone, simply because staff refused to return me to my cell before they sprayed another prisoner on my pod. Collateral exposure to pepper spray is used to divide and conquer and pit the men against one another. Staff will use what I call ‘playground psychology’ and say something like: ‘Well, if you don’t want pepper spray in your cell, talk to so-and-so about his behavior. Tell him to stop whatever he’s doing.’ It would normally be laughable for its child-like approach, except that it sometimes works because that pepper spray really affects people. Especially asthmatics like myself. This kind of abuse needs to be exposed, because there is no oversight.”

White Supremacy at Work

The judicial system and law enforcement operate within the boundaries of structural racism. What is unspoken is the presence of white supremacists in law enforcement and prisons. Letters I receive from prisoners all over the country call out white supremacists working as guards and staff. Some guards have no problem sharing this status with prisoners. Others have tattoos that show their affiliations with these groups.

In both policing and prisons, someone who is racist should not be able to be in a position of power over a group of people they hate. The Southern Poverty Law Center publishes a hate map, which shows where hate groups are. In Pennsylvania, where I reside, these maps coincide with where many of the prisons are.

Slave patrols were a way of controlling Black bodies and keeping them in captivity. When slavery ended, the Ku Klux Klan took over the role of keeping people in fear. Now, we have the Proud Boys, militias and other white supremacist factions. A Brennan Center for Justice report in August 2020 revealed that white supremacists have infiltrated law enforcement for many years, with police links to militias and white supremacist groups in many states across the U.S. People of color have reported this connection for a long time. Yet nothing has been done. Even during the ongoing protests, this line between far-right militants and police has been a factor, with the “militia” being somehow instructed by and protected by law enforcement.

Where’s the Accountability?

When guards assaulted my son and six other men during a peaceful protest from their solitary confinement cells, they filed a criminal complaint against the guards. In their case, the state police and the district attorney, whom my son had also filed a complaint against, worked together to charge them with riot, basically clearing the guards of any wrongdoing.

When prisoners file a complaint in Pennsylvania, the state police are supposed to investigate, but they never do. They interview the perpetrators, the guards, and gather no information from the witnesses, the prisoners. This one-sided form of investigation always turns out in favor of the guards. Prison officials and law enforcement investigate and exonerate themselves. This action is modus operandi in law enforcement internal investigations. The district attorneys rarely prosecute police officers or prison guards for their brutality or killings. One hand washes the other.

Where’s the accountability? Law enforcement, in general, has always had an impenetrable wall when it comes to protections. The police union, which initially started due to poor working conditions and low pay, has become an enabler of police misconduct. Studies in 2018 and 2019 found a direct correlation between police protections and police violence. Just like their counterpart, the prison guards union holds the same power of protecting misconduct. Guards are rarely fired for misconduct, even when a prisoner dies.

The legal doctrine of qualified immunity is one of the main ways law enforcement avoids accountability. The Civil Rights Act of 1871, or Ku Klux Klan Act, was enacted to protect African-Americans during the Reconstruction era. It allowed for those whose constitutional rights were violated to get relief through the courts. Section 1983, the modern version, adopted this act’s basis and allowed a public official to be financially accountable for violating a person’s rights, for instance, by police brutality or an illegal search. The Supreme Court’s decision in Harlow v. Fitzgerald in 1982 gave legal immunity to public officials who violate people’s constitutional rights.

Defund or Not to Defund

Police and prison guards who kill almost always claim to do so in the name of personal safety. They say they felt threatened or feared for their lives. According to Bureau of Justice Statistics, the number of officers killed between 2010 and 2019 was 511, with 48 officers killed in 2019. Since 2015, police have shot over 5,000 people, averaging about 1,000 people per year. The mortality rate of prisoners is hard to analyze because the actual number of prisoners killed by guards can be hidden. For instance, Pennsylvania used sudden cardiac arrest as the cause of death for John Carter, who died while being suffocated by massive amounts of pepper spray, beaten and repeatedly tased.

One of the current demands is to defund the police and abolish prisons. The “law and order” faction of our society and politicians have used this to spark fear. Understandably, those caught between being murdered by police and murder in the community are very conflicted about this defunding movement. But a lot of conversation is happening that wouldn’t have even been brought up or thought about before.

What is clear is the lack of understanding of what defunding means. That’s because there are multiple ideas around how it should look. Some believe the police’s role in society should be limited to law enforcement, not addressing homelessness or dealing with people experiencing a mental health crisis. Others feel that reallocation of funds to social service programs would decrease crime and enhance the quality of life for those in impacted communities. Abolitionists, like myself, think along the line of communities policing themselves and how transformative and restorative justice would work.

Defunding prisons is another critical component of the movement. That means putting money into intervention and diversion from incarceration. A suggestion I have made to public officials over the years is to educate and create jobs for both the prisoner and the guard alike. For instance, in my home state of Pennsylvania, prisons replaced the coal mines. These small towns fought to have prisons built in their communities for the sole purpose of providing jobs. Likewise, their state representatives are fighting tooth and nail to keep those prisons from being decarcerated. It is a gut-wrenching feeling to understand that one human being’s survival depends on incarcerating another human being. This detachment may account for the inhumane way that prisoners are treated.

What Community Leaders Think About Defunding the Police and Abolishing Prisons

Fawn Walker Montgomery, co-founder, Take Action Mon Valley

To me, defunding police and abolishing prisons is a necessary end. Policing and the criminal justice system are both rooted in white supremacy. This has led to gross injustices with Black and Brown people. Moreover, police rarely help when any person of color calls them (sometimes this results in death). If people really think about it, we have been our own policing for years now. This is especially true for the Black trans community.

Defunding means exactly what it says — defunding the police. I don’t like to say reallocate because it keeps white people comfortable, and if we keep doing that, nothing will change. Taking money away from the police and giving it back to communities of color (where a majority of overpolicing occurs) for social services, education, housing and transportation. It’s an initial step toward community-led public safety and alternatives to policing. Reform, training, and community policing are not working. Community buy-in to defunding should also lead to abolishing prisons as well as more acceptance to community restitutive justice practices.

Excerpt of Statement From the Amistad Law Project

The communities with the least violence are not the ones with the most police but the ones with the most resources. Strong, connected communities keep us safe. We keep us safe. We can and must defund the police and direct those resources toward community programs that prevent violence, that nurture young people, that treat people with mental illness with care and dignity. We need unarmed first responders who can respond to crises with care and connect people to services.

Carla Willard, Professor of American Studies, Franklin and Marshall College

It looks like an “instead”: Instead of police, we have MASSIVE mobilization of resources to impoverished areas with special investments in Black and Brown communities. Those resources would include a community network with Committee (not individual) leadership comprised in large part of peeps who are returning citizens and who want to be involved in conflict resolution. “Gang violence” could be engaged by peeps who have made it out — or who CAN now make it out because they are offered meaningful jobs and positions in communities. Peeps who continue to commit violence despite repeated attempts to engage — that’s the hard question. Any suggestions?

Gabrielle Monroe, Advocate and Activist in Pittsburgh

Defunding the police looks like decriminalization of prostitution and substance usage.

Defunding the police looks like an increase of available and friendly mental health services.

Defunding the police looks like less grants for academics to dictate police training based on their white opinion. More centering of communities affected by police violence and abuse needs to be integrated into academia. Center folks with lived experiences above academic opinion.

Defunding the police looks like an end to the “police expert” era. The police are experts on how to clean up after crime. They are useless in preventing crime or ending generational abuses. The police are not substance usage experts. The police are not houseless folks experts. The police are not sex worker experts. In fact, they rape sex workers during the process to “save” us. Stop centering police above folks with lived experiences. Defunding the police looks like the police taking a seat and LISTENING and CENTERING the communities police are claiming to “help.” Defunding the police looks like funding organizations who are on the ground doing the work.

Mary Marcus

As a past nursing instructor, I worked in Albany, New York, at the Capital District Psychiatric Center — CDPC. They had a crisis unit and a crisis team that, on request, met police at a 911 call for unstable behavioral issues. They were able to help police assess critical situations, and the crisis unit was the receiving center capable of evaluating behavior. That is where some of the money should go.

Tricka Parisimo, Human Rights Coalition

Defunding the police is essential if we want to truly be safe in our communities. It means that we, the people, look out for each other. It means that when someone is having a mental health crisis, there is funding for social workers and health care providers to keep them safe. Defunding prisons means that we prioritize healthcare over punishment. It stops the cycle of people of color being put in cages for decades because the system wants to keep people of color from having a voice. Our communities need to be nurtured. Our communities need to be funded. The police and the prison industrial complex were established by the 1 percent so that they could stay in the 1 percent. It is time that we form institutions that benefit the people.

Solutions Toward Change

There are some very obvious solutions to ending police and prison guard brutality. First and foremost, value our lives. Acknowledge systemic racism and biases in law enforcement and disparities in the judicial and incarceration systems. Quit using crime as the scapegoat for public safety when crime has consistently dropped every year. We need more intervention and less incarceration. That can happen by giving communities the resources and tools they need for intervention.

While we work toward decarceration, remove the focus in prisons from punishment to rehabilitation and education with work training that is sustainable and valuable to the communities they are returning to. Change the root cause of crime, which is poverty, by putting money into marginalized communities and raising wages. We need non-police ways of making our communities safer. Instead of building prisons and jails, invest in education and training for the future.

Related Information

Amistad Law Project Podcasts: “To Defund or Not To Defund” and “What #DefundThePolice Means”

Bobby Seale: Community control of police was on the Berkeley ballot in 1969

Community Control of the Police: An Idea Whose Time Came and Never Left

Law@theMargins’ Community Based News Room publishes the stories of people impacted by injustice and aspiring for change. Do you have a story to tell? Please contact us at CBNR. To support our Community Based News Room, please donate here.