By Farhad Mazhar, a Bangladeshi writer, columnist, poet, social and human rights activist, and environmentalist.

By Farhad Mazhar, a Bangladeshi writer, columnist, poet, social and human rights activist, and environmentalist.

In these dark times of the “War on Terror”, drone killings, collateral damages and bloody events such as the recent massacres in Lebanon, Baghdad and Paris, remembering a communist Moulana, the peasant leader from Bangladesh challenges our conventional narrative of cut and dry political ideologies into left and right, nationalists and internationalists, secular and Islamic.

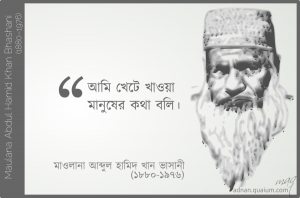

Abdul Hamid Khan (1880-1976) was the popular revolutionary peasant leader from South Asia, whose political career started in 1919. He was contemporary to M.K.Gandhi, (1869-1948), Jawaharlal Nehru (1889 -1964) and Muhammad Ali Jinnah (1876 – 1948) and popularly known as Moulana Bhashani. Bhashan was a river island in Brahmaputra River Valley, literally meant the place overflowed by the mighty flood making people destitute. Abdul Hamid Khan as a young peasant leader led the destitute to settle in Bhashan Char. That is how he earned his famous title, ‘Bhashani’ by settling the unsettled and the landless. For a brief period he attended the famous Dar-Ur-Ulum Deoband, the most eminent Islamic learning centre established in 21 May 1866 after the great anti-colonial Sepoy Mutiny of 1857. He was referred to as ‘Moulana’ not as a religious title but in reverence to his deep knowledge of Islamic spirituality and political discourse as well as for his commitment to the cause of the oppressed. He interpreted Islam in a unique and distinct way.

He is also known as a communist despite his criticism of them in his mature period because most of his life he relentlessly supported their cause and provided mass platform to preach and practice their class politics. Islamists have always been hesitant to accept him because of his scathing critique of Ulema’s social and political role and their non-egalitarian theologies that stand against the oppressed and according to him, inconsistent with the teaching and the politics of the prophet. Needless to mention, he was dear to the heart of peasants.

Bhashani Disrupts Binaries of History and Politics by Centering Our Focus on the Oppressed

Why is Moulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani so interesting and provocative? Why is he so problematical to our fixed narratives on secularism, nationalism, communism and other convenient discourses? One aspect is clear. He challenges the binary premises from where we interpret history and politics. We presuppose and privilege one over the other; e.g., secularism over Islam, Nationalism over the concrete class questions of workers, peasants, people washed away by river erosion, socially excluded, religious minorities, outcastes and other marginal section of the population. Moulana’s way of bypassing such binaries is simple. To him real human beings are more interesting than ideologies: ‘adorsher cheye manush boro’ — humans are above ideologies. He always insisted to deal with concrete human beings, and not imaginary entities constructed or defined by ideologies.

His adherence to a particular popular Islamic discourse is the second reason making him unique. He was a pir or murshid to his spiritual followers. However, he is not a representative of those popular saint figures sitting in his ‘darbar’ somewhere in a remote Bangladeshi village and singing Sufiana songs to teach people the value of spirituality. His was rather a unique posture. Spirituality is always political to Moulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani and an authentic spirit manifests in the culture of resistance against oppression.

He was a believer no doubt, but believer of a different kind. To him meaning of religious or theological texts are never fixed and they are always open to interpretation in the context of the real life struggles of the oppressed (majlums) against the oppressors (jalim). ‘The class struggle in Islam is between the oppressor and the oppressed’’ he said. Religiosity or spirituality is the divine urge of human beings in order to remain in communion with all spiritual beings. So any hindrance or barrier that disunites the community and makes the majority of the population enslaved to a few is not acceptable. Resisting and overthrowing the oppressor becomes the call of the day. This is the site where for him religious texts find their meaning and proves that spirituality is part of our nature to desire a community of equals with dignity and justice to all.

Consequently Bhashani’s Islam finds no contradiction with socialism or communism and stands on equal footing with Marx and Mao Ze Dong, but carefully drawing distance from their lack of spirituality. Communism to him is a community of divine souls, and not merely of agents of production, consumption and exchange. While western enlightenment despiritualised the meaning of revolution by reducing human beings into economic agents, Moulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani brought political spirituality to the revolutionary struggle of the people. One may reasonably argue that the revolutionary Marxist project, which is essentially a western enlightenment project to resolve the contradictions of capitalism and egocentric modernity, collapsed because it has lost the ethico-political meaning of historical agents called ‘human beings’ Moulana Bhashani brought it back in the figure of Islam and revolution. One can hardly ignore the potential power of his revolutionary imagination after the collapse of actually existing socialism and the rise of Islam as a force of resistance against imperialism and global capitalist structure. This is the third reason why one can hardly ignore him anymore.

Further, he challenges us with a new ideas of governance without a coercive state structure or dividing the community between rulers and the ruled. He named it ‘Hukumat E Rabbania’: governance based on love and the supreme obligation to nourish and sustain all life forms, as Allah does to the world, to all life forms visible or invisible irrespective of race, religion, hierarchy in nature or in society.

Hukumat-e-Rabbania: Meaning of Divine Governance

Bhashani is intellectually fascinating because of his explorative idea of ‘Hukumot E Rabbania’, the notion of governance that must premise upon the life affirming values. With regard to life and livelihood Allah does not make any distinction among any human beings because of their origin, color, religion, class, gender or any other identity.

Hukumat E Rabbania is derived from the philosophy of ‘Rububiat’ ( or ‘palonbad’ as Bhashani used to translate the same in Bangla). Rabubiyah or Rabubiayat is derived from Arabic word Rab, meaning the supreme sustainer or ‘nourisher’. Obviously, the word also implies the lordship of Allah but what is emphasized here is not his sovereign power of lordship but his immediate material presence as the provider of care and nourishment through his creation.

From giant elephant to invisible microbes and human beings in between – all have the right to live, be nourished and sustained. This is what Allah, the RAB, the great ‘Nourisher” does to all. He does not distinguish between human beings and non-humans, does not care whether one is Hindu, Muslim, Christian, Buddhists Communists or atheist – each and every life form is entitled to the glory of his creation. Sun shines on all, river flows for everybody, land is for everyone one to use to earn a livelihood. No one can claim ‘ownership’ excluding others from use of Allah’s creation to sustain their lives in the world. Such denial is un-Islamic and contrary to the supreme nature of Allah. The Quranic notion of ‘Rab’, who takes care of us all, has a powerful message that easily reaches to the oppressed.

Bhashani was indeed contemplating on a vision of communism without the coercive structure of state and capital and environmentally destructive rule over nature envisioning the authentic community of human being respectful to environment, ecology and all life forms to appear on the historical horizon. Such imagining of the future is possible in Islam, since Islam glorifies human beings as ‘Khalifah’ , the representative of Allah on earth, meaning the divine role assigned to human beings is to be the caretaker or steward of Allah’s creation. To be Allah’s representative is to emancipate from the ‘Nafsaniyat’ (selfish egocentric desire) to initiate the phase of ‘Ruhaniyat’, the divinity or spirituality. Ruhaniyat (political spirituality) can be achieved at the personal level as well as historically, through Islamic revolution. Moulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani was imagining an economic and ecological revolution and a form of governance that is appropriate for the community of the divine souls free from Nafsaniyat or destructive egocentric desires to rule others and appropriate the world for personal consumption.

To teach his followers what does he mean by ‘Palonbad’ Bhashani says it’s like a parent caring for his children, addressing their needs and scarcity. Primary role of the parent is not to be the ruler over the members of the family, but to be the caretaker for them. ‘The charming relation of love between the father and the children’ should be reflected in the art of governance. ‘As a ruler one may implement a command, but the ultimate result is never positive’, Bhashani says. He was absolutely against ‘Shashonbad’ – the form of state that is based on the relation between ruler and the ruled.

“Unless we accept something spontaneously from our heart the external pressure only complicates the matter. Authoritarian arrogance in Shashonbad tears apart the relation between human beings creating cleavages. The ruled see the ruler suspiciously and rebels whenever an opportunity arises. Therefore there is no place of Shashonbad (the ruler-ruled relation) in Islam. Islamic governance is full with the pleasant and hearty relation of love and nourishing care. There is no hierarchy between the ruler and the ruled. The objective of the Islamic revolution is to establish Rabubiat or the principle of nourishing and the care”

That all life forms have the ‘right’ to be nourished and sustained is a very powerful proposition. Bhashani did not use the term ‘right’ as defined by positive law and implemented by the State, through the ruler over the ruled, but often as the powerful Islamic notion of ‘huq’, the ethico-moral obligation functions by the power of the Ruhaniyat (political spirituality) of the community. This is what he imagined as ‘Hukumat’, the governance by spiritual wisdom. Bhashani has always viewed State as a problem, and not a solution, instead he insisted on Islamic spirituality that is obligatory for all Muslims. A Muslim must strive hard to be the caretaker of earth and realize the ‘huq’, the ethico-moral right of all life forms. It’s the divine obligation and responsibility to care and nourish each and every creation that is what matters to be a Muslim. Islamic revolution is the accomplishment of the political task of creating and enabling the political environment for such human beings to appear and act as agents of both history and natural evolution.

Bhashani Must Be Understood as an Anti-Colonial Figure & Rooted in the Peasant Movement in Bangladesh

Efforts to understand Bhashani requires an understanding of what the words Muslim and Islam mean in historical context of Bangladesh, particularly with regard to the land rights. Bhashani gradually became the leader of the most powerful peasant movement that successfully used the emancipating interpretation of Islam to liberate themselves from Zaminders (landlords) and Zamindary systems, a colonially imposed feudal land ownership arrangements.

Landlords or Zamindars were collectors of revenue and had no ownership rights over land. But the British colonial ruler in the permanent settlement recognized them as owners of soil thus depriving the peasantry their right to land. Zaminders were given permanent hereditary rights to collect revenue precipitaing antagonism and conflict between peasants and the landlords.

Peasantry fought against this injustice under various banners of Islam. Resistance against the oppression of the colonially created landlords triggered Islamic discourse to represent the peasant movement and articulate their cause. This historical fact is very important to understand Islam in Bangladesh and the peasantry, who were largely Muslims. The Islamic political movement in Bengal, therefore was essentially a movement of the peasantry for land rights, overhauling the rule of property British imposed upon them.

Pakistan came into being in 1947 and within years then East Pakistan passed State Acquisition and Tenancy Acts (1950) to abolish Zamindary systems imposed by the British colonial rule. Mowlana Bhashani proved that Islam is capable of generating popular narratives that could be a key factor in mobilizing peasantry against colonialism and eliminate colonially imposed feudal land owning system. A new rule of property in East Pakistan was installed extending far reaching impact in the formation of a new society and a new Muslim middle class who soon rediscovered their cultural origin in the Bengali language and the rich tradition of Bengal delta. Soon in 1972 Bengali people succeeded in curving geography as their own motherland, a red and green national flag and a seat in the United Nations. Bangladesh appeared in the world scene. It was simply impossible to even imagine if it was at all possible without Moulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani.

The details of his history are not what we like to enter here now, but he demands our serious attention. Bhashani stands in contradiction to cold war communists who learned to juxtapose their ideology against Islam, despite the presence of a successful revolutionary peasant leader who demonstrated how one engages with religion or for that matter any ideology to bring forth a real transformation. Islam played a significant role in eliminating colonial rule of property in Bangladesh.

Moulana and the Project of the ‘Modern State’

A critical reflection on his life and available speeches and writings indicates that Moulana Bhashani was not at all fond of modern state in either forms: bourgeois or Bolshevik types, which are centralized instruments of power. Both left and the right blamed Bhashani to be an anarchist, though he was not. He remained linked to the powerful Islamic notion of ‘Ummah’, without ever mentioning it, in projecting the possibility of emergence of the real global community, where people could relate to each other not by any earthly relations, such as property, commodity or money but through the mediation of the divine, who is invisible but always present in all of us. To realize the divine we must eliminate all exploitative relation including its highest form, i.e., capitalism. Coming of a global community, where society is run by the ethical and moral values and not by the omnipotent powerful state or law imposed from outside, is possible only after the radical destruction of capitalist relation and our destructive relation to nature.

“Red Moulana”: Bhashani Presents Us With a Political and Spiritual Paradox

Available literatures on Moulana Bhashani is essentially flawed because the left extracts only that part of his life to project a ‘Red Moulana’, the ‘prophet of violence and revolution. The Islamists are equally wrong because they reduce him only into a Pir, an Islamic spiritual leader and deduct the best part of his life activity in promoting communist ideas. He presents a very interesting paradox. He is both. But no one takes both part of him together.

Moulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani vehemently opposed that trend of communism lacking spirituality in its subjective principle and political activities because of the denial of the divine nature of human beings as prescribed by Quran, and equally he opposed those Ulema who are blindly glued to their theological texts and unable to decipher meaning responsibly for the real material world to demonstrate the spiritual and political value of Islam.

So he remains a challenge till today and we must re-invent him in this dark era of ‘war on terror’. Moulana questions our prejudices, presuppositions and rhetoric, by both right and left, about Islam, about secularism, about the meaning of political spirituality. He ceaselessly reminds us about unconditional necessity to act within the people’s own narratives about their world and not to try to fit everything into neat theories. To say it simply, reality and history cannot be reduced into cut and paste precooked theories. It must be animated by people’s struggles.

If we could appreciate the challenge we face in understanding Moulana Bhashani, the great revolutionary of our time, we could also realize why he is important now, at the present juncture of history defined by the global war on terror and various ideological forms of resistance under Islam. Resistance against the brutality and the injustice of the global world order is a reality and people will inevitably resist the oppression by various ideas and ideologies that speak to their their heart and articulate their cause. Islam is definitely going to play a role in the articulation of those causes. Bhashani’s ideas have all the potentiality to set a political direction that is free from the legacies of Islamic theologians and traditional communists. He despised them both.

His appeal is increasing in the present political reality of Bangladesh. It’s not easy any more to push him under the debris of forgotten history. I may confidently claim that he will definitely shed new lights in defining our global political task in the era of war on terror and dehumanization of emancipator projects and the role of political spirituality in revolutionary visions and actions.

References:

Bari, Syed Irfanul: Mowlana Bhashani bolechen: Tangail, Hukumat-e-Rabbania Andolon er pokkhe Muhammed Abdul Latif Miah, 2000

Bhashani, Mowlana Abdu Hamid Khan, Rabubiater bhumika, Tangail, Hukumat-e-Rabbania Samity Prokashonu, 1974

Bhashani, Mowlana. ‘Palonbad ki o Keno?’ In ‘Rabubiat: Mowlana Bhashanir shesh kotha’, by Syed Irfanul Bari, 18-19 Tangail, Hukumat-e-Rabbania Andolon er pokkhe Muhammed Abdul Latif Miah, 2002