By Chaumtoli Huq, Editor of Law@theMargins

By Chaumtoli Huq, Editor of Law@theMargins

When we speak about freedom of speech or dissent in Bangladesh, invariably and understandably the conversation turns to bloggers whose murders were claimed by Islamic group Ansarullah Bangla Team. In 2015, four bloggers were killed including Avjit Roy a year ago on February 26 while walking outside Dhaka University. Since then, Washiqur Rahman Babu, Ananta Bijoy Das, and Niloy Chatterjee were also killed. These killings by non-state actors no doubt raise serious concerns regarding the safety of citizens from brutal violence both in the busy streets and in their homes. It raises the utter failure of the police and state to provide protections to both citizens and non-citizens. The murder of Italian aid worker last year was claimed by IS took place in the diplomatic quarter of the capital.

However, in presenting the bloggers as exemplars of dissent, and their deaths as evidence of the suppression of free speech and further that that the greatest threat to speech in Bangladesh is a fringe Islamic group, obscures the reality that there is a more greater threat to dissent in Bangladesh. It obscures larger political and economic forces at play.

I share some thoughts on other examples of protest, dissent and speech to illustrate that the greatest threat to speech in Bangladesh comes now from the state, in particular the current political party consolidating its power since its unopposed election in 2014 by manipulating the legal system to retaliate against segments of society including journalists, civil society activists and workers. Further, the state is arranging police and other paramilitary forces deftly under a War on Terror rhetoric to suppress opposition meanwhile pursuing aggressive neoliberal economic policies which displaces tea workers from their land and denies garment workers basic labor rights. Further, under the guise of regional cooperation, Bangladesh is further aligning with India’s similar path of neoliberalism. The protests and state retaliation in JNU is an indicator of serious concerns for dissent in South Asia.

Journalists of varied political backgrounds find themselves at the opposing end of the state. Mahmadur Rahman, a business person and owner/editor of Amar Desh, a paper viewed in opposition to the current Awami League government has long been subject to harassment by the courts and government through charges of sedition. Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) raised concerns with these charges. On 14 December 2012, the government charged Rahman with sedition for publishing Skype conversations, illegally hacked by other parties, between Justice Mohammed Nizamul Huq chairman of Bangladesh’s International Crimes Tribunal, and Ahmed Ziauddin, an international criminal law expert and war crimes activist based in Brussels.

Invoking sedition is curious as a vestige of English colonial law that was historically used against anti-British nationalists. Human rights groups have remarked that seditions charges have disproportionately been used by the state to suppress opposition views. That known freedom fighters who have fought for the liberation of Bangladesh are being charged with sedition in the interests of national security reveals both the absurdity of these charges, but also the urgency of the state of crisis for dissent.

More recently Mahfuz Anam, Editor of English daily newspaper Daily Star in Bangladesh, has been sued for defamation for publishing materials against Prime Minister’s Hasina’s alleged involvement in corruption activities during the caretaker government, which he recently admitted perhaps was not the best journalist decision. Here, it should be mentioned, that as a general rule defamation as a legal case is actionable only if the statement published is knowingly false, and comments against public officials carry a heavier burden to show malice. Thus far, there is no indication that Mr. Anam knowingly published the material against Sheikh Hasina or acted with malice. But, Prime Minister came out recently calling for his resignation of Daily Star and that Editors will be treated like war criminals. This is concerning since war criminals have been given the death penalty in Bangladesh.

Another cause of concern for speech is the selective use of Information Communication and Technology Act. ICT Act. The Act was heralded as a advancement to modernize Bangladesh through technology, yet, has been used to regress in areas of speech and democracy. According to the Section 57 of the ordinance, if any person deliberately publishes any material in electronic form that causes to deteriorate law and order, prejudice the image of the State or person or causes to hurt religious belief the offender will be punished for maximum 14 years and minimum 7 years imprisonment. It also suggested that the crime is non-bailable. This provision of ICT shows its potential to be abused and used against free speech. It has been used against Human rights lawyer Adilur Rahman.

Examples also abound of the use of law to suppress dissent by the judiciary. In 2014, British born Dhaka based journalist David Bergman was found guilty of contempt by the War Crimes Tribunal for blog posts he had written that raised questions about the official death toll during Liberation war. The International Crimes Tribunal was set up in 2009 in Bangladesh to investigate and prosecute suspects who allegedly committed war crimes during the 1971 war of independence war with Pakistan.

In response to the judge’s contempt decision, a cross section of activists and intellectuals expressed concern over the judgment, and found themselves answering to contempt charges as well. In it, they questioned the broad use of contempt powers of the court as a relic of colonial England. They rightly raised questions of free speech and how this action would diminish dissent in Bangladeshi which is essential for a thriving democracy. Of the 50 activists charged, some rescinded their statements, expressed apologies, while others continued to respond to the proceeding. Eventually, public health activist and freedom fighter Zafrullah Chowwdhury was found guilty of contempt. The collateral damage to this legal and judicial harassment is a frightened civil society, fearing imprisonment for articulating ideas, and squashing of any space for dissent.

With sedition, defamation or contempt, the state employed the judiciary and the legal process to retaliate against journalists, civil society activists and lawyers to suppress any opposing views. Invoking the national security language of the War of Terror, state have justified their actions to subordinate free speech and civil rights. This threat to dissent to a cross section of Bangladesh society is a greater threat than any fringe Islamic group. This is not to excuse the brutality of those murders, but those murders operate and are highlighted to incorrectly suggest an exceptionalism or differentiation from the state’s actions. I would ask can we render equivalent the state who has access to judiciary and police at its disposal to an unknown Islamic group. Whose interests are served here to highlight solely the murders by non-state actors and not the ones by the state?

While these cases of suppression of speech clearly falls within the ambit of what we traditionally understand as free speech, and international human rights groups have spoken up where local activists are not able; however, there is another form of speech that should be highlighted which is also being suppressed. That speech is of workers organizing for improved working conditions, and their overall fight for a dignified life, which squarely challenges dominant economic models that seek to present Bangladesh as a lucrative place for investors.

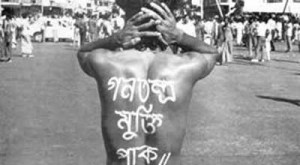

The labor movement of garment workers and more recently tea workers in Northern Bangladesh whose protest messages questions the Government of Bangladesh, and its model of economic development that counters global economic interests is often not viewed as examples of speech based dissent. It is dissent, but not considered speech because it operates outside the traditional domains for speech: media, courts. The failure to view the organizing by workers as a form of free speech limits possibilities for cross sectional, cross-class organizing among journalists, lawyers civil society and workers groups.

Garment workers who protest find themselves brutally and physically silenced through the Industrial police and baton. There, the police often in collusion with garment owners use their force to suppress speech, and bring false cases such as vandalism to retaliate against organizers. Of course, workers have endured this brutality from police long before we have seen the recent cases against journalists.

Promoting this as speech and worthy of protection not just as an economic right but as a political right is not one that serves the interest of Government of Bangladesh to consolidate its political power nor the interests of foreign investors.

There is also a classism inherent in defining what is speech and dissent. The bloggers, on-line, with a higher level of formal education are writers and “intellectuals”. In contrast, garment workers and tea workers while they use their body as the platform to communicate their speech, they are simply workers. They are not viewed as guardians of speech in the way that media is viewed. Yet, they literally put their bodies on the line for dissent.

Focusing on non-state, fringe Islamic groups as a threat to democracy in Bangladesh hides the failure of the Government of Bangladesh to provide bloggers protection, and suggests an otherwise vibrant civil society when in fact the space for dissent by each segment of society is limited. Journalists, lawyers, civil society activists charged with contempt, defamation and sedition show an aggressive use of the legal system to suppress dissent among a wide segment of society. Further, the use of police to suppress protests by labor groups reflects another use of the state to suppress opposition views.

Limiting speech to bloggers, traditional writers like lawyers and journalists, as agents of speech reveals the limitations of free speech as a mobilizing principle because its contours ultimately remain bounded to a certain class and segment of society. If our activism remains in that realm, I fear we can not counter this legal harassment by the state. If we broaden our understanding of dissent and speech, and observe the ways in which the state is invoking the legal process to suppress speech, we can forge a broad based movement for democracy. It has been done before, in the history of Bangladesh, and can be done again.

Freedom of Speech not mean that Freedom to talk against Islam or Criticize Islam and Muslims.

[…] and vulnerable minority communities alike. Overreactions from security forces–along with the opportunistic harassment and broad suppression of opposition members–have led to increased polarization and hardening of mentalities and […]

[…] and vulnerable minority communities alike. Overreactions from security forces—along with the opportunistic harassment and broad suppression of opposition members—have led to increased polarization and hardening of mentalities and tactics. An even smaller […]