Living on the streets brings extra interactions with law enforcement, which can lead to being further displaced from society, but Tennessee’s capital is taking steps to reimagine justice.

By Hannah Herner and Vicky Batcher

Editor’s note: This story was produced in partnership with The Contributor, a street media paper in Nashville, Tennessee, and is part of “The Right to a Home,” a Community Based News Room (CBNR) series that examines homelessness issues across the United States. CBNR is a project of Law@the Margins, and the series is supported by a Solutions Journalism Network grant. Vicky Batcher was a subject for this story and also contributed reporting and writing.

NASHVILLE, Tennessee — Paul Arndt knows all about people experiencing homelessness having encounters with the police. He used to live in the recently closed encampment under the Jefferson Street Bridge, a place where many nonprofits frequent, giving aid to the homeless living there.

Every so often, police will force these encampments to clear out, citing trespassing laws. But his first real issue with getting a citation happened when he was selling The Contributor, the biweekly street newspaper published in Nashville, in front of the popular downtown tourist spot Puckett’s Grocery & Restaurant.

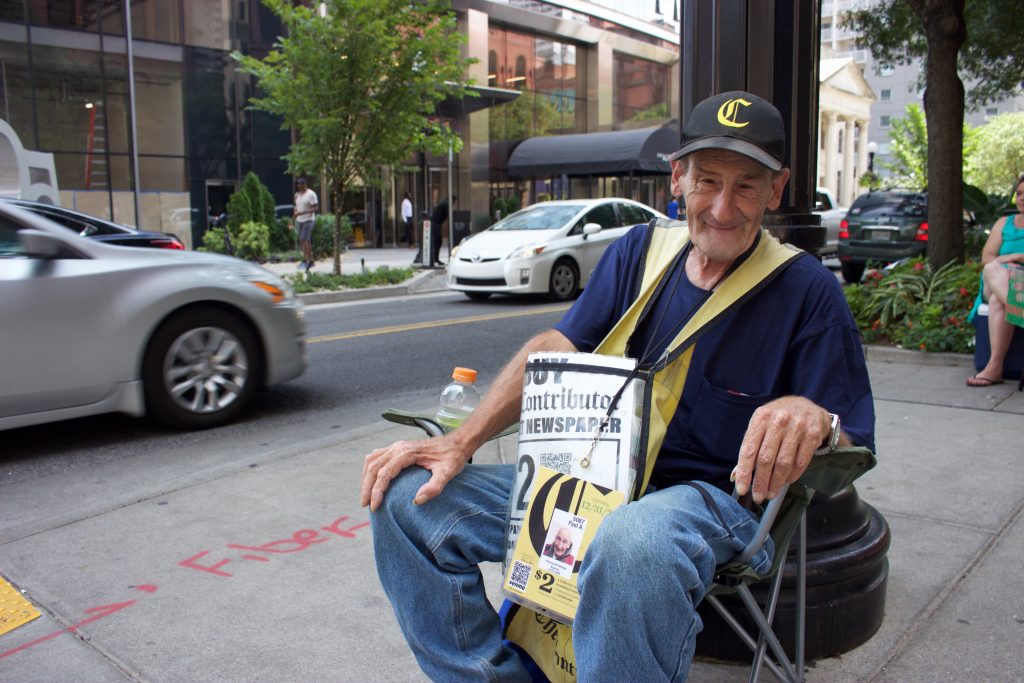

Paul Arndt sells The Contributor in his camp chair in his typical spot. He was arrested for obstruction of passageway in the following weeks. (Hannah Herner)

Arndt is 65 years old and legally blind. Unable to stand for long periods of time, he had brought a camp chair to sit on while he worked. The owners of the business knew him and welcomed him in the months he had been selling there. Then one day, a police officer came by and issued him a citation for obstruction of passageway.

Arndt recounts that an officer came by and said, “I could arrest you for having that chair on the sidewalk, but I’m not going to. Instead I’m going to give you a ticket.”

The following week, the same officer came by and arrested Arndt for sitting on a stool while selling his papers. This time, he said, “I’m thinking about arresting you.” Arndt said, “Go right ahead. I’m not doing anything wrong.”

The officer then cuffed him and took him downtown, booked him and locked him in a cell. Three to four hours later, a woman with the police department came in and spoke to Arndt. She explained that he wasn’t allowed to obstruct the sidewalk like that and stated they would be releasing him.

“I felt picked on being homeless and all,” Arndt said.

What’s a Crime?

The city of Nashville is in the beginning stages of offering alternatives to the typical criminal justice system, but that doesn’t stop businesses or private property owners from making calls to the police about people experiencing homelessness — which leads to a lot of people being asked to move out of sight.

In Nashville, from January to October 2019, 464 people experiencing homelessness were arrested for criminal trespassing, according to data from Metro Nashville Police Department. Many of them got arrested on this charge more than once, making it a total of 724 arrests. In that span of 273 days, that averages out to 2.6 arrests per day. In that same time period, 37 people experiencing homelessness were charged with obstruction of passageway.

At the Central Precinct, located in the heart of Nashville, Cmdr. Gordon Howey encounters people who are homeless often. He says criminal trespassing and obstruction of passageway are two of the most common charges seen amongst people experiencing homelessness.

“Hearing complaints come in over the police radio from citizens, trespassing tends to be something that occurs each and every day —somebody calls in about someone in a parking garage, in a door, in front of a business, a stairwell, things like that. Not with every encounter with an officer is an arrest made, but there’s the potential for it,” Howey says.

A population harder to collect data on is those living in their cars.

Vicky Batcher, co-author of this story, has lived in an RV for the past two years. She’s received some knocks on the window, with “sorry you can’t park overnight here” from some local Metro officers, but for the most part, they’ve left those living in their cars alone. Places that are open 24 hours have the best chance of being left alone but are usually far from much-needed services and food, she says. Walmart used to be a safe place, but some people who are living in their cars have seen a crackdown on those living in cars parked in the parking lot, even their own employees, Batcher added.

Vicky Batcher stands by the camper where she lived for two years. (Linda Bailey)

“The private security companies like the one that works for Walmart wouldn’t even let us park in their lot to do shopping without some sort of harassment,” she says.

Batcher has encountered threats of being towed and jailed if she didn’t move the RV, which gave her anxiety attacks. She was evicted from a dwelling seven times in 25 years, and memories of being thrown out into the street after each eviction brought back the fear of once again having to turn to the streets.

“Threatening to have your only home taken away from you is a below-the-belt blow just for parking,” Batcher says. “It made me feel like an eviction all over again. I was scared and not sure what to do when I left. A person waiting to meet up in a parking lot is given more leeway than someone homeless.”

How People in Poverty Experience Criminal Charges

Part of Stephanie Harris’ job at Metropolitan Development and Housing Agency is to work with people to get charges expunged from their record to better their chances at getting employment and housing. Having navigated the court system with many low-income folks, she says people enduring poverty experience the court system much differently than more affluent people. Money is owed for fines, court fees, even classes to be taken as an alternative sentence. It also costs to have those charges expunged later, if eligible. Harris says she advocates for court outcomes to be the same across income levels.

“Let’s say the same shoplifting charge,” Harris says. “I go in with a [hired] attorney, and it’s my first charge. It’s a given that my attorney is going to ask for diversion, the expungement option, to be written into my disposition, so that if I complete probation successfully, I can just pay my fee and get it expunged. Somebody else might go in, and they’ve gotten arrested, and they’ve been kept in jail because they couldn’t bond out. Nobody is at home taking care of their children, so they plead guilty and get out and go home or go back to work.”

Having any guilty charges on your record can affect employment opportunities, Harris explains, and it’s not uncommon for hiring done through a computer system that rejects anyone with a guilty record, regardless of what kind of charge it was.

Free Hearts, a local advocacy organization led by formerly incarcerated women, started a #ItsNotACrime criminalization of poverty campaign in response to some of the things they were seeing in the community. Gicola Lane, statewide organizer for Free Hearts, says she saw a man experiencing homelessness charged with theft of a grocery cart. He was sentenced to prison because the value of the cart was above the threshold for a misdemeanor. The group has been collecting feedback from people experiencing poverty to inform recommendations to local and state government.

“A lot of people just say, ‘No one has ever asked me this before,’ ” Lane says. “No one has taken the time to say, ‘Is it fair?’ If someone has money, they can get out of jail, but because I don’t, I have to sit there?”

Addressing the Problem: Homeless Courts

Some Nashville organizations are working toward addressing the repercussions of the criminalization of homelessness and poverty.

The Nashville office of Baker Donelson law firm is in the planning stages for a homeless court.

The firm will draw from its work at the monthly Homeless Experience Legal Protection (HELP) pro bono hours with people at Room In The Inn, an organization that organizes shelter for and offers educational services to those living on the streets. This new homeless court will have a specific docket and meeting time that only deals with charges like criminal trespassing, possession, public urination and public intoxication, says Christopher Douse, chair of the Nashville Pro Bono Committee and coordinator of HELP for three years.

In April of 2016, Nashville activists rallied on Public Square and marched through downtown to the Fort Negley homeless encampment in an attempt to prevent the imminent arrest or evictions of the residents. (Alvine)

“It’s serving a need,” Douse says. “We’re providing an avenue for what are typically these minor criminal issues that disproportionately affect the homeless population to come forward and be on a streamlined docket with a court that is understanding the population that’s coming before them, and working to clear those off with dedicated time from public defenders and the [district attorney] to work on it. Otherwise, they get lost in the mix of everything else that’s going on.”

Nashville would join Los Angeles, New Orleans, Chicago, Boston and Houston, and a number of other cities in having a homeless court. The Nashville court is looking at best practices for a homeless court in New Orleans, where the HELP program also began.

Katie Dysart, coordinator for the homeless court in New Orleans, says a best practice is to organize a community of contacts, from local housing and employment resources, to the local bar — it’s about adding value to the homeless community. She adds that the homeless court has lightened the general sessions court docket and gotten fines and fees traded for things like community service or maintaining employment for a certain period of time for people experiencing homelessness.

“Many homeless individuals are barred from housing, employment, or other basic daily activities given outstanding warrants that carry fines that they cannot pay.” Dysart said via email. “The Homeless Court has been able to get these folks into housing, employment, and satisfy fines without monetary contribution.”

Crisis Treatment Centers: Alternative Holding Spaces to Jail

Mental Health Cooperative, an organization that offers mental health services to low-income Nashville residents, created a facility that seeks to keep people out of the criminal justice system to begin with. The newly built crisis treatment center serves mainly people on TennCare or without insurance, and offers an alternative to jail, where police officers can bring people having a mental health crisis, when they have become a danger to themselves or others. One of the drivers to building this center was to streamline the process for police, where they could get back on the street as quickly as possible.

“Homelessness in and of itself, you could call crisis,” says Jacob Henry, supervisor of emergency psychiatric services at Mental Health Co-Op. “There’s just a lot of stressors that come with that — how am I going to care for myself? Where am I going to spend the night? Especially as we approach the winter. But looking at it from our standpoint, [we serve those who have] a psychiatric crisis. Sometimes, the crisis of homelessness can lead to a psychiatric crisis, or vice versa. There’s a connection there, and I think that’s why you see high rates of people with mental health issues that are homeless.”

The Crisis Treatment Center allows for expedited police drop offs for people experiencing a mental crisis. (Mental Health Co-op)

Davidson County Sheriff Daron Hall, says the reality of society is that the police are often called on to address mental health and homelessness. And it’s not always as severe as the threat of suicide or homicide, which is what the Crisis Treatment Center covers. When the sheriff’s department started looking into why people were repeatedly being put in jail, a couple of the top reasons were failing to do things the criminal justice system asked them to do, such as attending a court date or meeting with a probation officer. When you fail to do those things, a warrant for your arrest is issued. If a police officer comes into contact with a person with a warrant, they have to arrest them, even if the charges end up getting dismissed in court later — the Crisis Treatment Center isn’t an option at that point. But the Behavioral Care Center, which is slated to open in March 2020 and also staffed by Mental Health Co-Op professionals, will be.

“I believe there’s going to be a need for our beds in this system, unfortunately, because the criminal justice system is asked to solve the mental health problems a lot of times,” Hall says. “It’s not a great thing, but that’s where we are.”

With the Behavioral Care Center, the booking room — the first step for someone taken into custody — will have a jail staff member and a mental health staff member. The people who qualify to be moved directly to the Behavioral Care Center would be charged with a misdemeanor, which is what 80 percent of charges are, and diagnosed mentally ill by the mental health professional. Court, jail time, probation and all the fees that go along with it could be waived if a person voluntarily goes into treatment. Part of the plan is also to have a support system waiting when they get out, be that inpatient or outpatient care.

“A lot of homeless people are arrested more than one time in a year, and more than one time in a month even,” Hall says. “Those are the candidates that we’re looking for. People who aren’t being served well at all by the criminal justice system… It keeps happening because you’re doing nothing to help what’s driving the issue.”

In these proposed solutions, the police are still called on to make decisions to defer to other service providers, or not. There’s still some interaction between the police and people who are homeless, often in an area outside of police specialty.

Lindsey Krinks, an advocate for people experiencing homelessness and co-founder of Open Table Nashville, a homeless outreach and education organization, says proposed solutions to criminalization of homelessness such as the Behavioral Care Center should prompt a larger conversation about the policing system in Nashville. She sees a need for including groups like North Nashville’s Gideon’s Army, which serves as violence interrupters and comes to the scene of shootings.

“When there’s a shooting, they’re on the scene, and the police are too. But they’re able to mediate in a way that the police are not,” Krinks says. “We need the same thing for the mental health system, for situations of homlessness and poverty. Homelessness is not a criminal justice issue. It is an economic issue. Mental health issues are not a criminal justice issue. They are mental health issues. Public intoxication is not a criminal justice issue. It’s a public health issue.”

She says a win for the community is the Nashville Outreach Team for Encampments, which came out of the encampment task force she was part of after the city closed Fort Negley, a longstanding homeless encampment in Nashville. This team can serve as first responders, alongside or instead of the police.

“When people see an encampment, they call the police, and instead of having the police be the first responders when there’s no instances of breaking the law other than trespass, [there could be a more effective response],” Krinks says. “We said it’s a best-practice in other cities to have a homeless outreach team respond.”

Krinks added, “I would like to see Nashville — and there’s a number of people talking about this and working toward this now — have a different kind of first responder that doesn’t just include law enforcement but also includes trained professionals, for certain calls. Certainly police are going to be needed in situations where violence is involved or weapons are involved.”

While many of these solutions are in their infancy, Nashville is about to have more options than ever when it comes to helping to decriminalize homelessness.

But it’s up to the police and the community to use these resources thoughtfully — to change what justice looks like for those experiencing homelessness.

Hannah Herner is a writer and media manager for The Contributor. Originally from Ohio, Hannah graduated from Ohio State University and served an Americorps service year in East Nashville before working for The Contributor full time.

Vicky Batcher is a 56-year-old mother of twin boys, vendor and writer for The Contributor. She was homeless for seven years and recently got into government housing. She now enjoys the benefits of having her own housing.

Community Based News Room publishes the stories of people impacted by injustice and aspiring for change. Do you have a story to tell? Please contact us at CBNR. To support our Community Based News Room, please donate here.