There are over 37,000 homeless veterans in the United States, and about 600 of them live in Chicago. For those who want help and qualify, a new federal government program could knock down some past barriers to housing.

By Lee Holmes

Editor’s note: This story was produced in partnership with StreetWise, a street media paper in Chicago, and is part of “The Right to a Home,” a Community Based News Room (CBNR) series that examines homelessness issues across the United States. CBNR is a project of Law@the Margins, and the series is supported by a Solutions Journalism Network grant.

CHICAGO — The roughly 600 homeless veterans on Chicago’s official list is “just the tip of the iceberg,” says Marvin Gardner, vice commander of Veterans Strike Force (VSF), which he said is the only volunteer-led organization in a Veterans Administration hospital.

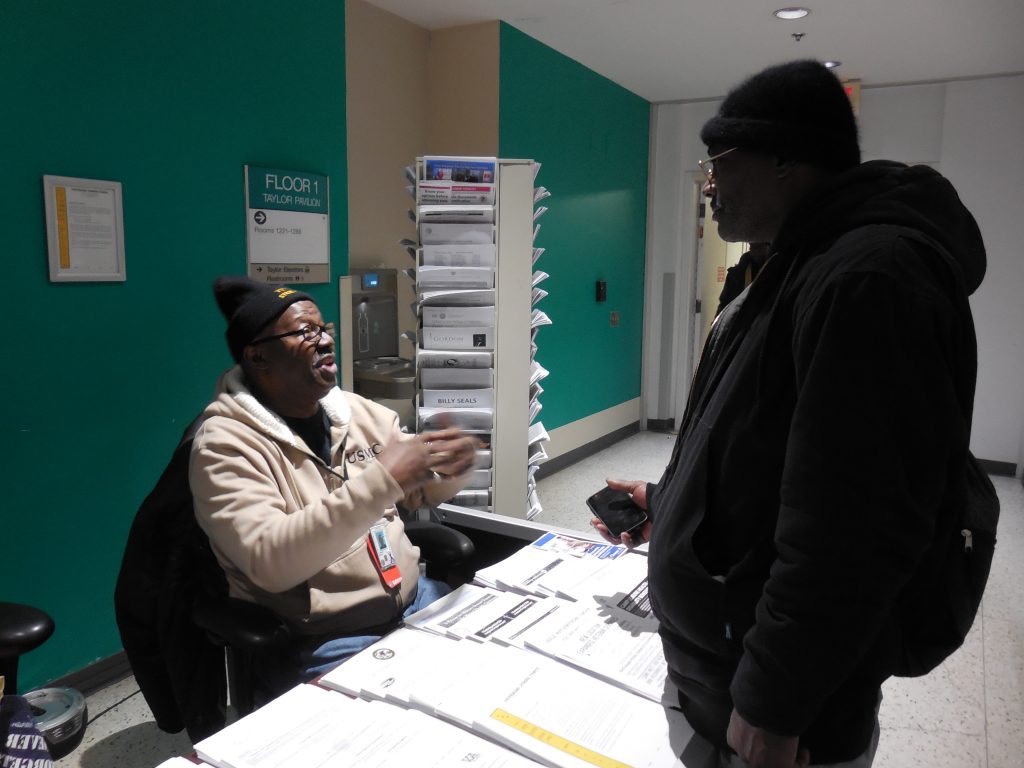

VSF, whose mission is “Vets Helping Vets” to become self-supporting, staffs a table at the end of a long, skylit corridor four mornings a week at Jesse Brown VA Medical Center, 820 S. Damen Ave. in Chicago. Vets from all branches of the military, from about age 20 to 66, stop by to talk and to pick up information on their Veterans Affairs (VA) benefits as well as city, county, state, federal and nonprofit agencies that help with emergency housing, employment, going back to school or even reentry for veterans who have been in prison. Showers are available at Jesse Brown VA, and VSF members often know homeless vets by name.

“A lot of guys coulda seen something in the military, had an experience, don’t want to come into the VA for help, just live off the land. Some don’t even want benefits. They just want to be left alone,” Gardner said, “because of how they were treated in the military, what they saw in active duty.

“A lot of them coming out of the military from Iraq and Afghanistan are coming out with screwy discharges. They went into combat, saw the damages of combat and wanted out so [the military] said, ‘You want out, we are going to give you a discharge but put ‘personality disorder’ on it so you can’t get benefits,’” Gardner said. “Really, the situation is, they ran into some kind of racial discrimination and didn’t do enough time in the military.”

PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder, is also a factor. Vets lock themselves in the basement, and their parents, who can’t deal with it, send them out onto the streets with no income and no benefits.

“A lot do have PTSD,” Gardner said. “I was undiagnosed for at least 20 years. I didn’t even know I had suffered from it. I couldn’t fit into mainstream society. I couldn’t hold down a decent job, couldn’t provide for my family. I couldn’t sleep because I had dreams of what happened to me in the military.”

Because he contemplated suicide, he went to Jesse Brown VA from 7 a.m. until he went to work at 3 p.m. “Just to feel safe and nobody hassling me. Luckily, I ran into these guys,” he said of VSF.

Gardner served in the Marine Corps from 1972 to 1975 during the Vietnam era, in Thailand and off the coast of Cambodia. They were doing exercises and were on standby for the rescue of civilians during the fall of Saigon in 1974.

Unlike Vietnam, which was fought in the jungle, the Iraq War was guerrilla warfare in a city with streets and houses, he said.

Soon after the Iraq War started, one young Marine Corps returnee was real shaky. “He left a hostile urban environment [in Iraq] and came back to one. Now he’s real leery about riding past dumpsters, riding down the street, period.”

In the United States, there are 37,085 veterans who are experiencing homelessness, according to “Point-in-Count” estimates for January 2019, a 2.1 percent decrease since 2018.

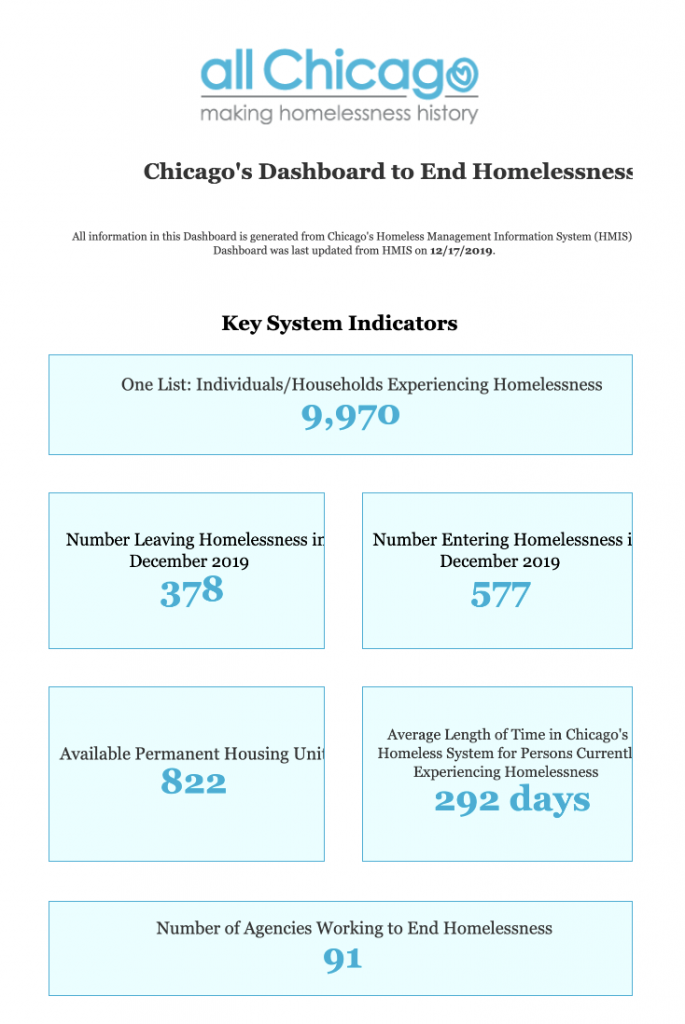

Among the roughly 600 veterans who are homeless in Chicago (as of Dec. 17), the largest number (232) is age 56-65, followed by 121 who are age 46 to 55 and 103 who are at least age 66 — old enough to qualify for full Social Security and Medicare benefits.

The remaining homeless include 18 veterans who are age 18 to 25, 75 who are age 26 to 35, and 64 who are age 36 to 45. The numbers come from Chicago’s Dashboard to End Homelessness, which is updated every Monday by All Chicago Making Homelessness History, which coordinates the 91 agencies receiving federal funding toward that goal.

Among the homeless vets, the largest number — 294 (48.4 percent) are matched with services and awaiting housing. Another 106 (17.4 percent) have been assessed but not yet matched, while 98 (16.1 percent) have not yet been assessed; 88 (14.5 percent) had been matched once and needed a rematch; and 22 (3.6 percent) were unable to be matched.

Every Veteran Doesn’t Want Help

Chicago’s veteran homelessness is not for lack of money, said Abraham House-El, program coordinator at Featherfist, which has five veterans programs in Chicago.

“One of the hardest things I do here at Featherfist is spend the money given to us by the VA,” House-El said. “Everyone that’s in need of help doesn’t necessarily want it. Chronically homeless veterans that are sleeping around on the streets in tent cities, when our Featherfist folks approach them, they want nothing to do with our people. Sometimes we have three or four conversations before we even get a name. Sometimes doing an assessment is next to impossible. There’s also a number of veterans that have mental health challenges that make it impossible on their own to get to organizations.”

That’s where a system navigator, or social worker, would help find these people.

Military Sexual Trauma (MST) is another issue VSF hears about. Women volunteers will walk a female vet down the hall to hear her story, Gardner said.

But MST doesn’t just affect women, said Reginald Lee, 58, who chanced upon the VSF desk during our interview. Lee served in the Navy from 1980 to 1983 after the fall of the shah of Iran.

“I was on a ship, and I went out with officers,” he said. “I had been warned, but I thought it was a joke. They were married. They said, ‘I want to have sex with you.’ It was a macho thing, before ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,’” which allowed gays to serve in the military, even though it forced them into secrecy.

Lee said he was forced to sign papers that he was gay, which was labeled “a personality disorder” on his discharge that affected his benefits.

There’s a lot of talk nowadays about “resilience,” about building up people’s strengths. Did Lee think people entered the military already damaged, after difficult childhoods?

“Yes, a lot,” he said. In his case, he enlisted to escape gangs in Chicago. After his attack, he didn’t seek VA help until he read a GQ magazine article on MST among men in September 2014.

Lee receives $771 in Supplemental Security Income, a federal benefit given to disabled adults and children. He’s lived the last seven months in a transitional housing program with Thresholds, which provides services to people with mental health conditions. He was unsure if he was on the Chicago Dashboard list of homeless veterans, but he knew he was on a Chicago Housing Authority list.

VA Tests a New Subsidy in High-Rent Cities

The VA has shifted its focus to housing veterans with barriers such as insufficient income, unemployability, recent evictions, bad credit, mental or physical health challenges, or just inability to pay market rent. This is a population that is receiving VA or Social Security benefits and not likely to see increased income anytime soon, House-El said. They’re rent-challenged, a population in their 50s and 60s — like more than half the veterans on Chicago’s Homeless Dashboard. The VA formerly emphasized chronically homeless veterans, but vouchers have brought those numbers down, and the VA has found it difficult to process large enough numbers of them.

A new VA Shallow Subsidy that began Oct. 1 helps veterans who can’t get Section 8 vouchers in high-cost cities like Chicago, Honolulu, Seattle, New York City, Washington, D.C. and five cities in California. In Chicago the program pays 35 percent of the fair market rent, and the veteran pays the rest, House-El said.

Around the far Northwest Side ZIP code of 60631, for example, the Shallow Subsidy will pay $339 toward rent, he said. On Apartments.com in December, there was a listing for one $835 one-bedroom apartment and one $900 studio, which would mean a cost to the veteran of $496 or $561, respectively.

In the Near North Side ZIP codes of 60610 and 60611, and the Lakeview ZIP code of 60657, the Shallow Subsidy would be $479. Near North Side rents started at $1,000 on Apartments.com, but only $729 in Lakeview, so that the cost to a vet would be $521 and $250, respectively.

Reginald Lee, for example, gets $771 in SSI, so if an apartment were $729 and the subsidy paid $479, the remaining rent would be $250. Theoretically, he could afford that rent, because it would be roughly 30 percent of his $771 SSI benefit. “A $750 unit today probably went for $425 at one time,” House-El said regarding the effect of gentrification on rents.

“Now that person with $750 a month in income can afford that studio on the North Side,” House-El said. “My hope is that landlords on the North Side will consider the Shallow Subsidy since 35 percent of their rent is being covered by us.

The subsidy is only in place for 24 months right now and may be just a test, but if this experiment proves successful in getting more veterans housed, it has lasting potential.

“If the data suggest it’s one of the best things we could have done, that more veterans are staying housed, it’s a factor in eliminating veteran homelessness, it won’t go away,’ House-El said

More people can be served with the Shallow Subsidy than with vouchers, he added, especially in a gentrifying city, because the subsidy covers only 35 percent of housing rather than 80 percent. But the subsidy covers only the cost of “light touch” case management, so it would not be appropriate for veterans who need more aggressive case management.

The point is, the VA is subsidizing the people it can find, and those people are low-income and older, which is the major part of the Chicago list.

While this initiative won’t end veteran homelessness, it’s a start.

Lee Holmes lives in Chicago and has experienced homelessness.

Suzanne Hanney, the editor of StreetWise magazine, contributed reporting.

Community Based News Room publishes the stories of people impacted by injustice and aspiring for change. Do you have a story to tell? Please contact us at CBNR. To support our Community Based News Room, please donate here.