The U.S. Supreme Court’s recent decision in Janus v. AFSCME is only the latest attack on the right to organize in a country where that right is constantly in peril. In August of 2000, Human Rights Watch published a report titled “Unfair Advantage” that found “freedom of association is a right under severe, often buckling pressure when workers in the United States try to exercise it.” In 2002, the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Senate Committee of the U.S. Senate held a full committee hearing regarding the findings in that report. Not much had changed by the time Maina Kiai, United Nations Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association made an official visit to the United States in July of 2016. In discussing the labor situation in the U.S., he states that market fundamentalism “overwhelmingly favours the wellbeing of employers over workers.” He goes on to detail the many difficulties workers face in exercising their right to freedom of assembly. Some recent organizing may be changing this, however. He explains:

In law, workers are not prevented from forming unions. However, in practice the ability to form and join unions is impeded by a number of factors: the inordinate deference given to employers to undermine union formation; a so-called “neutral” stance on unions by authorities, when in fact international law requires that they facilitate unions; weak remedies and penalties for intimidation, coercion and undue influence by employers; and political interference and overt support for industry at the expense of workers. While employers can hold captive audience meetings and one-on-one meetings with supervisors to dissuade employees from unionizing, workers have no right to distribute union literature in the workplace, conduct meetings without management being present or engage in protest activity on the employer’s property. The pervasiveness of employer interference practices are vividly illustrated by the strength of the $4 billion dollar ‘union-busting’ industry.

Right to Work Laws Impede Organizing

One uniquely American obstacle to organizing is the existence of right-to-work laws. These laws, passed in 28 states including all of the South, prevent workers from negotiating clauses in their contracts that require every employee covered by the contract to pay their fair share in dues And the South in particular has proved especially difficult to organize. In addition to right-to-work laws, hostile employers there combine with reactionary government leaders and business advocacy groups to create what one organizer called “the anti-union trifecta.” While purported to be in the interest of freedom of association, right-to-work laws are in fact just a way to undermine workers’ rights, with workers in these states experiencing lower union density, lower wages and lower benefits. Janus has effectively made public sector jobs in all states right-to-work.

But right-to-work laws have not won. Massive teacher strikes in the spring of 2018 were predominantly in right-to-work states, beginning with West Virginia . In fact, not only is West Virginia a right-to-work state, but strikes by public employees there are illegal.

New Modes to Build Worker Power

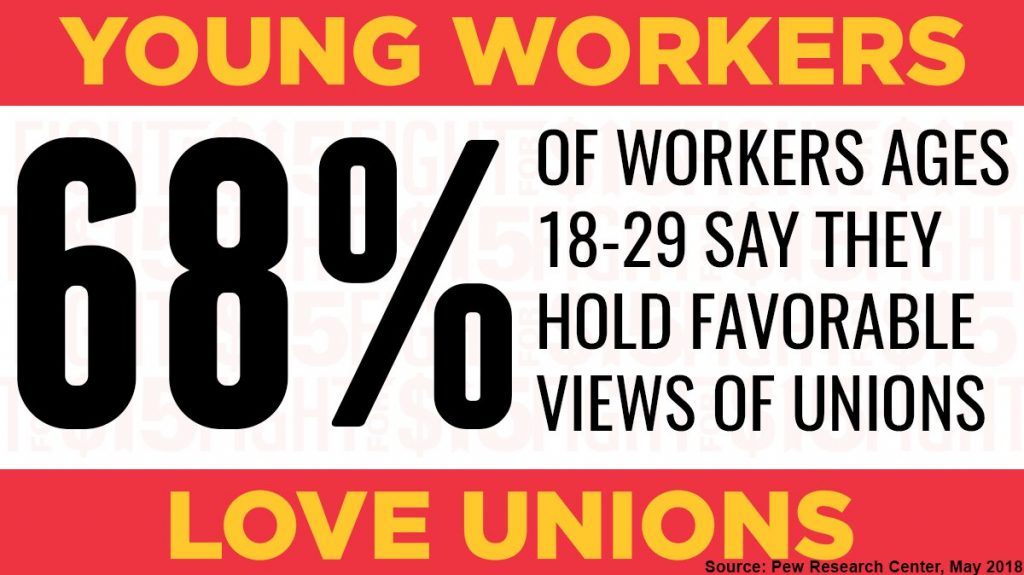

[dropcap]L[/dropcap]abor organizers are exploring new ideas for building worker power, from reaching out to millennials to looking to Europe for ideas. Millennials have proven to be solidly pro-union, realizing that unions are key to ensuring living wages, safe working conditions and justice on the job.Some ideas are as old as labor organizing itself. Hotel workers in Stamford, Connecticut experienced an inspiring organizing victory by focusing on building democratic control of the union from the grassroots level. The solidarity built by these workers was also seen in the organizing victory at the only Lipton Tea plant in the U.S., in Suffolk, Virginia, where workers stood together across racial lines in facing racist attacks.

A very promising development is the recent defeat of a right-to-work law in Missouri, making it only 27 states that have right-to-work laws. Passed last year by a Republican legislature and signed into law by a Republican governor, implementation of Missouri’s law was delayed and a referendum forced by unions and their allies. Given the chance to weigh in on the right-to-work legislation, voters rejected it and the shackles it puts on their right to organize.

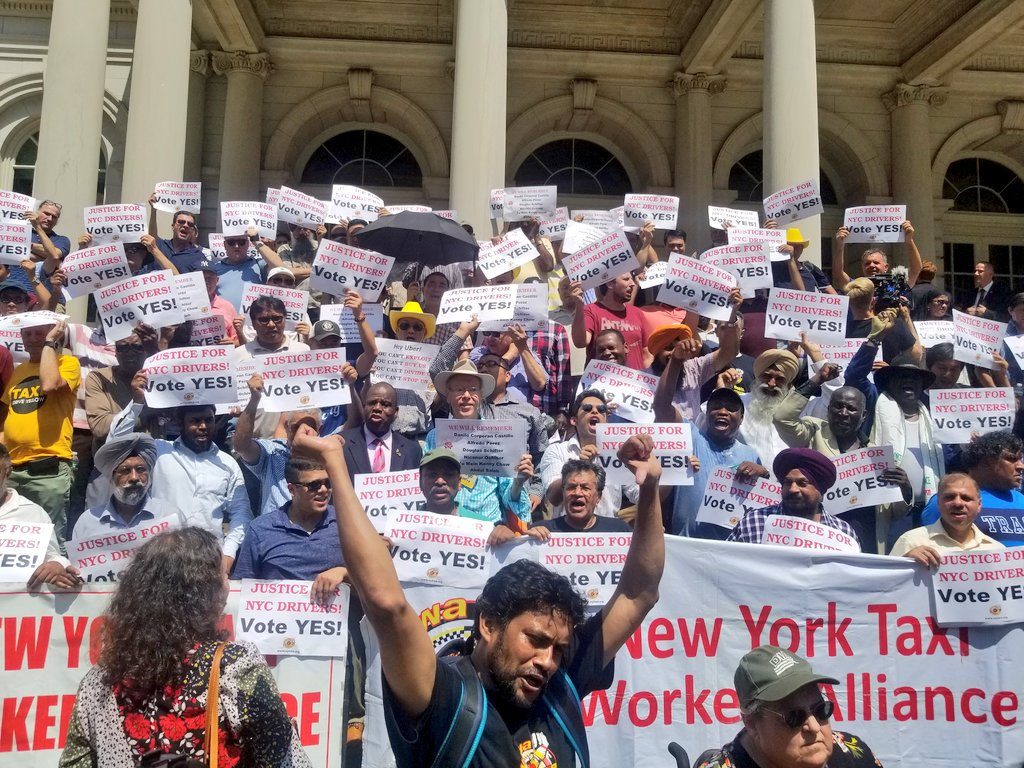

New York Council also passed the first every municipal legislation to address the working conditions of New York City drivers. The set of bills will cap the number of for-hire vehicles for a year while the city studies the booming industry. The bills also allow New York to set a minimum pay rate for drivers.

We should be encouraged by these developments which underscore the importance of organizing to ensure worker power.