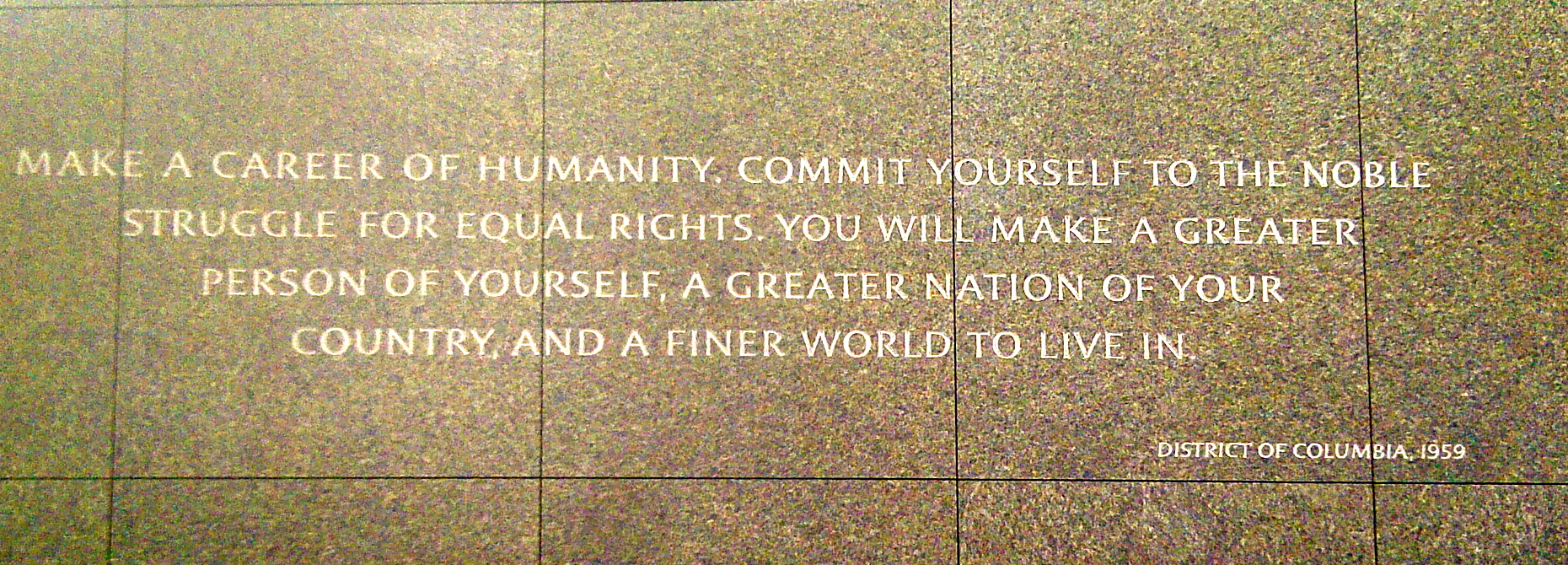

— Martin Luther King, Jr. , 18th April, 1959

Last year, in 2012, Chief Judge Lippman announced a new pro bono requirement for all applicants seeking admission to the New York State Bar to perform 50 hours of legal services under the supervision of an attorney. Pro bono service is defined generally as any law-related activity performed for low income or disadvantaged individuals. This new requirement was intended to address what he called the “access to justice gap” in our state for many low-income litigants who cannot afford an attorney. He states that this requirement would also help new attorneys “build valuable skills” and imbue in them the “ideal of working toward the greater good.”

http://www.nycourts.gov/attorneys/probono/baradmissionreqs.shtml

While there were criticisms of this requirement, namely that it would burden young law students, who are already saddled with debt to provide pro bono services, the new requirement was generally praised. The mechanics of how this requirement will work is being sorted out, but I agree that it is a positive step in the legal profession. It sends an institutional message that public service is an integral part of our professional identity such that pro bono requirement is a requirement to practice law in New York. Hopefully, attorneys will continue to provide pro bono services even after they are admitted. However, there is no such requirement for continued pro bono service after admission.

This new pro bono requirement should have an impact on how we teach students in law school. Because students will now work with populations that are in need, and could begin as early as their first year, law schools should integrate theory and skills that would be necessary for students to be successful in their pro bono service.

There are several ways first year faculty can incorporate social justice themes and skills into their curriculum. In the first year Legal Practice course that I teach, students research and write legal memos and participate in interviewing and counseling simulations. The fact patterns that I chose for students typically highlights a social justice issue. For example, last year, my students researched under New York law whether a person with a prior criminal conviction would be permitted to teach in an educational setting. Through simulations, students interviewed the client played by an actor. In those simulations, they learned to interview, build rapport, and through building interviewing skills, we discussed empathy. I provided excerpts of client testimonies on problem solving courts and supplementary readings on our criminal justice system to put “our client’s” case in context to other cases and within the law. Students grappled with their own understanding of the criminal justice system with their desire to help “our client” who was denied a job.

In other first year classes, faculty can provide historical context to some current social issues students may observe. For example, property or contracts professors can show how racial restrictive covenants bar African Americans from purchasing homes in certain areas, which lead to the neighborhood segregation that we see today. Or they can simply ask students about the public policy implication of the cases they are reading. We can make readings on cross-cultural lawyering mandatory in the first year. There are many more creative ways to integrate social justice themes into the first year so that when students are working on their pro bono matter they have the skills to represent clients, the emotional intelligence to understand their situation, and an understanding of the socio-historical context in which their client is experiencing the denial of justice for which they need the student’s assistance.

Law schools under the guidance of faculty should facilitate opportunities for students to engage in pro bono service. With faculty guidance, students cannot only gain practical legal skills in representing a client, but also can gain an enriched learning experience by reflecting on their experiences with faculty.

Integrating social justice themes in the first year will no doubt change the focus of the first year and I think law school education in general. This change will be for the better because it will tune students in early in their career to their ethical obligations as legal professionals.