There isn’t enough money to organize poor people. There never is enough money to organize anyone. If you put it on the basis of money you’re not going to succeed. So when we started organizing our union, we knew it had to depend on something other than money.” Cesar Chavez, On Organizing and Money (1971)

Janus v. AFSCME is about money. Money that Mark Janus, a child-support specialist in the Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services, does not want to pay for the employment benefits and job security he enjoys as a result of AFSCME (American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees) union organizing. It is about the money conservative donors have given to finance the legal attack on public sector unions, middle class families and communities of color. It is money that unions need to remain financially independent. While a decision against AFSCME and public sector unions will be a huge set-back, if we limit our conversation on the future of the labor movement around fair share fees and money, as Chavez’s quotes suggest, our movement will not succeed. We have to offer something more.

Background on Janus

On Monday, February 26, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Janus v. AFSCME where Mark Janus, who does not belong to the public sector union AFSCME, objected to paying an agency fee for collective bargaining activities on grounds that the fee violates his First Amendment rights. It is unclear from these arguments which direction the Court may decide but labor unions fears that the Court will decide in favor of Janus.

Under current law, every public employee may choose whether or not to join a union, but unions are required to negotiate on behalf of all workers, regardless of whether they join the union. Because public employee unions negotiate employee benefits and rights covering all employees, and must represent all workers in the bargaining unit, employees who decline membership have been legally required under Abood v. Detroit Board of Education to pay fees, sometimes called “fair share” or “agency” fees, that cover the union’s representation costs. This decision from 1977 has been affirmed over the years, and most recently, in Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association. In an earlier piece on Law@theMargins, Professor Ann Hodges shared some of the concerns of adopting the position by Janus, including that it will reduce unions’ power and effectiveness. She writes:

“A ruling in favor of the objecting teachers will allow them to benefit from the representation without paying for it, free riding on the union dues paid by other workers. The reduced funds will limit the money available to the union to represent workers….. Reducing the bargaining power and advocacy of unions will exacerbate the growing economic and social inequality in the United States. Although union membership has declined in recent years, unions remain one of the few organizations capable of limiting the power of corporations and extremely wealthy individuals. If the oppositional voices of unions fade, the influence of already powerful wealthy elites and corporations will increase. Democracy works only if there are multiple sources of power.”

Those same concerns exist under Janus. There is no question that if the Supreme Court permits individual workers not to pay their fair share fees for the costs of administering a collective bargaining agreement, then, it can weaken the union because it will reduce resources for organizing. Even the lawyer for Janus conceded as much during arguments: “Well, to the degree to which the union resources are diminished by individuals exercising their First Amendment right not to subsidize that union, I submit that’s a perfectly acceptable result.” For a longer discussion on the issues of fair share fees and the Janus case, see an Economic Policy Institute Report here.

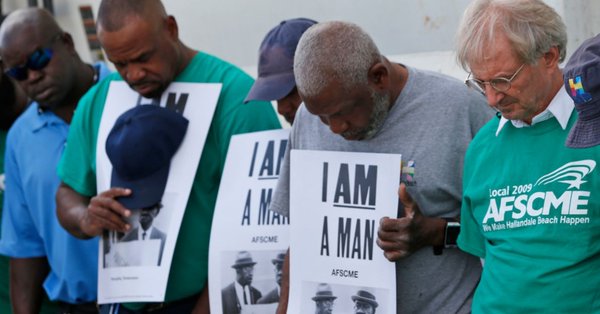

It should be noted that the attack on public sector unions such as AFSCME is also an attack on workers of color, especially black workers, and civil rights broadly. AFSCME is the nation’s largest and fastest growing public services employees union with more than 1.6 million working and retired members. In the 1960s, AFSCME struggles were linked to the struggles of the civil rights movement. This year is the 50th anniversary of the sanitation workers strike with the powerful slogan, “I Am A Man,” which resulted in the city of Memphis recognizing the AFSCME Local. Through steady organizing by public sector unions, all workers, especially black workers, were able to secure a middle class life through living wages, health insurance, and pensions. Black women, who make on average $17.92/hour in the public sector, and $13.08/hour in the private sector, are most benefitted from a strong public sector union, and will be most affected by Janus. Strong public sector unions help all families achieve a middle class life which is increasingly impossible. It is therefore no accident that conservative groups have deliberately set out to defund public sector unions, and the underlying racism of this approach is telling in their efforts to undermine the effectiveness of AFSCME.

Labor Unions Remain Viable Institution for Working Class

Despite its challenges, and critiques, labor unions remain the institution that have challenged the conservatism in politics. It is why corporate funders have identified public sector unions as their target, as they see unions as foundations for progressive organizing. Since the 1990s, corporate donors like the Bradley Foundation have given $30.5 million to 24 conservative groups that have supported the legal assaults against public sector unions. The two sponsors of the Janus case, the National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation and the Illinois Policy Institute’s Liberty Justice Center, have between them received $1.6 million in Bradley donations since 2003.

While a favorable decision for Janus will be a huge set back to unions, which should be fought vigorously, and should not be minimized, we must remember that a favorable decision for Janus is not a defeat to organizing. Already, we have seen the labor movement respond in unity, with the leaders of the four largest public sector unions comment on the Janus case. As indicated from the Chavez quote above, the labor movement must offer something more than financial resources to build worker power. Even in an ideal situation where every member is paying dues, unless we are offering a labor movement that is engaged with each and every one of its members, and we create a culture that is supportive of labor organizing, we will be at a disadvantage to the billionaire corporate donors.

Worker Centers Like NYTWA Offer A Labor Organizing Model Regardless of Janus Decision

One of the reasons unions have been able to retain a certain level of independence and autonomy, and as a result political power, is because they rely on their own members for resources through dues. However, much of the relationship between unions and their members have been reduced to this transactional fee for service relationship, and as the earlier quote by Chavez mentions, it is not money alone that will build worker power.

We can learn from low income and communities of color that have been engaged in labor organizing for the last three decades into workers centers without the benefits of a union structure and dues system. It is not without its challenges, as most of these organizations are under resourced. However, unions can look at the organizing success of New York Taxi Workers Alliance, where their driver members are regulated by city agency Taxi Limousine Commission, but are excluded from forming a union because they are classified as independent contractors. They can look at their successful and confrontational organizing against Uber called #DeleteUber which led its CEO to step down from Trump’s Business Advisory Board; months later, the entire Board was disbanded. In New York, they have sued Uber for wage theft. They obtained a successful administrative labor decision to deem Uber driver employees under state unemployment insurance law.

NYTWA has been organizing drivers in New York City since the mid-1990s, and has prioritized an organizational structure where they are supported by membership dues from drivers for their political campaigns and advocacy. As of 2018, Bhairavi Desai, Executive Director of NYTWA, notes that 87% of their revenue is supported by driver funds. It is not surprising that NYTWA is the first worker center given a charter by AFL-CIO and the only worker center that serves on it Executive Committee.

The AFL-CIO calls the NYTWA an organizing committee similar to nascent unions spawned by the CIO in the 1930s that figured out how to bring collective power to industrial workplaces. They organize drivers who many said were not organizable. By focusing its organizational resources on building its membership, encouraging payment of dues, cultivating the culture of a vibrant labor movement, NYTWA has managed to avoid some of the pitfalls of worker centers that are reliant on funders. For a good discussion on this challenge, see Whose Movement Is It? Strategic Philanthropy and Worker Centers. NYTWA has been able to critique efforts by unions that seek sweetheart deals with corporate employers like Machinists and Uber. In this cruel gig economy that has led to the tragic suicide of driver Douglas Schifter who shot himself in front of City Hall, we are going to need to do more than limit our movement to the issue of agency fees for collective bargaining agreement. We have to move away from fighting for the declining members under union territorial battles compromising union solidarity over expediency.

Another model trade union we can learn from is the New York City Worker Federation Freedom Cities campaign, which takes a multi-sector approach to labor organizing and makes demands that go beyond the workplace. In addition, the New York Worker Center Federation includes worker centers organizing street vendors, domestic workers, laundry workers, and other sectors to build frontline worker leadership through a training institute.

Historically, we also know that the farmworker movement began because Cesar Chavez and Delores Huerta committed to creating the social culture where volunatarily workers pay for their union. Chavez recounted stories of some farmworkers who are the least paid, who still sacrifice a portion of their income to build their union. This culture of wanting to build and support one’s union without regard to legal constraints echoes back to the radicalism of the International Workers of the World (IWW). This union rejected business unionism, in which unions are merely administrators of contracts, in favor of solidarity unionism, where all workers are seen to be in solidarity with each other.

Whatever the outcome of Janus, public sector trade unions should not—and cannot—revert back to union “business as usual.” Instead, they should look towards historical models of labor organizations that were forced to organize under legal conditions that did not allow for any dues, and yet were able to forge successful models of labor organizing that energized all members. They should learn from labor organizations like NYTWA. Janus is a wake up call to us to heed lessons from solidarity unionism of IWW and learn from NYTWA today.

Thanks to labor and employment lawyer Jonathan Harris for his feedback on this article.