By Shahana Hanif, Associate Editor

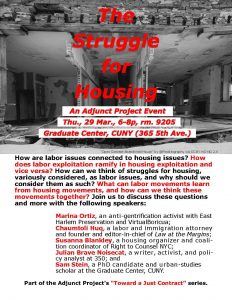

The Lenape ancestors were honored as a remembrance that we are on stolen Lenape land. Each speaker presented their work and visions in response to prompts that explored the ways in which labor exploitation ramifies in housing exploitation and vice versa, how struggles for housing require a labor perspective, and emergent strategies and lessons each movement can integrate for a more coalescent future. Law at the Margins Associate Editor Shahana Hanif, previously a tenant organizer at CAAAV: Organizing Asian Communities, was especially drawn to each activist’s insightful voice and commitment to reimagining futures that continue to center working-class communities and the power of organizing on both housing and labor fronts. Here are some of the encouraging lessons:

Samuel Stein, a geography PhD student at the CUNY Graduate Center and an Urban Studies instructor at Hunter College, opened the panel by acknowledging communities’ collective labor into making a neighborhood. This includes the labor of social reproduction, of physical maintenance, of advocacy and activism, of institution building, and more. All the more collective labor is required of working-class communities when their neighborhoods are disinvested and denied social benefits and public services. In fighting against gentrification, he stressed that communities are also fighting to retain the neighborhood markers which they produced. Alongside representing rising housing costs, displacement and replacement by investors and wealthier residents, gentrification reinforces the theft of collective labor and the alienation of people from the spatial product of their work.

Marina Ortiz, an anti-gentrification activist with East Harlem Preservation and VirtualBoricua, expanded on gentrification in her neighborhood and spoke truth to how 38% of East Harlem natives do not qualify for Department of City Planning’s (DCP) East Harlem rezoning plan, a proposal to expand opportunities for affordable housing. “We cannot afford these apartments. This plan provides nothing for East Harlem families. And further, does nothing to combat NYC’s homelessness.” As a result, East Harlem Preservation engaged over 3000 East Harlem residents in an effort to petition against the plan and its dire repercussions. Majority knew nothing about the rezoning efforts and upon learning more, refused to get behind it and adamantly pushed back.

Marina Ortiz, an anti-gentrification activist with East Harlem Preservation and VirtualBoricua, expanded on gentrification in her neighborhood and spoke truth to how 38% of East Harlem natives do not qualify for Department of City Planning’s (DCP) East Harlem rezoning plan, a proposal to expand opportunities for affordable housing. “We cannot afford these apartments. This plan provides nothing for East Harlem families. And further, does nothing to combat NYC’s homelessness.” As a result, East Harlem Preservation engaged over 3000 East Harlem residents in an effort to petition against the plan and its dire repercussions. Majority knew nothing about the rezoning efforts and upon learning more, refused to get behind it and adamantly pushed back.

Both Samuel and Marina discussed the tensions between labor unions and tenant organizers, because some unions see the housing developments as a source of jobs for their members. They underscored how important it was to look at these issues together. For example, a 32BJ SEIU member, also the last rent-controlled tenant in his building that is at risk of demolition, testified calling for better jobs and wages for affordability. He didn’t call on the need to protect rent-stabilized apartments and tenants. These are not separate talking points and should be presented in parallel. The battle continues for East Harlem residents.

In his presentation, Julian Brave NoiseCat, a writer, activist, and policy analyst at 350, centered the life of Joe Waukazoo, a 62 year old homeless Urban Native from the Fruitvale neighborhood in Oakland, California. Julian’s slideshow opened with a photo of Joe Waukazoo on 30th Avenue and International Boulevard paying homage to the Ghost Ship memorial. The Ghost Ship is a deadly face of the process of gentrification and unaffordability in the Bay Area. In 2016, the Ghost Ship, a warehouse that had been converted into an artist collective, caught on fire killing 36 people. During the same year, Joe was displaced from this Section 8 housing and is among the more than 5000 homeless people living under BART train tracks and empty lots. For Julian, displacement is not a story of the last ten years. Rather, for indigenous communities, the struggle for housing is an intergenerational tragedy. Native folks have been fighting dispossession in America for generations with little relief to reclaim home.

From his talk, attendees were left thinking critically about the ideas of housing, a quantifiable unit, versus home, which refers to one’s roots and being rooted in a place. For Julian, these two are not the same but reveal that for indigenous communities in particular, the solutions to undo displacement are unlikely. In the fight for housing and homes, indigenous communities continue to be under attack.

Building on Julian’s emphasis on housing crises in California, Chaumtoli Huq highlighted the transnational connections of her work in Bangladesh and New York contesting land, housing insecurity and precarious labor. She focused her presentation on issues in the US. She noted that labor laws often exclude domestic workers, farm workers, building supers, and many other live-in workers from its protections. This exclusion reinforces a false belief that live-in workers must be sufficient because they have access to stable housing but it makes them vulnerable to employers.

Chaumtoli also raised the challenges of campaigns like Fight for $15. Even if the minimum wage is raised to $15, workers will still be unable to rent affordable housing in the US. Work and tenancy go hand in hand in that, landlords look for “good tenants”. To be one requires a regular flow of income, employment history and credit history. “Bad” tenants are often precarious workers with no guaranteed income and inability to afford rent, thus resulting in housing conditions that permeate overcrowded living situations. Overcrowding in housing, especially rampant among NYC’s immigrant communities, must not be overlooked in conversations about public health, homelessness, and access to jobs.

Chaumtoli’s point resonates with Shahana’s organizing work in public housing and rent stabilized buildings across NYC and Kensington, Brooklyn with Bangladeshi tenants. The lack of affordable homes and the defunding of public housing, jobs that pay in accordance with the rising cost of living, legal immigration status, and other insecurities reinforce harmful, illegal living conditions. Among this is overcrowdedness, which is also how many families survive separation and the burden of homelessness. For working-class immigrants, the language access piece is crucial in tenant organizing and must include tenants whose languages are not English/Spanish. Read more about CAAAV’s push for language access in NYCHA and their multilingual tenant organizing.

Chaumtoli concluded her presentation with a call to especially protect precarious workers and those with criminal records. Doing so requires bringing back radical direct actions, referencing tea workers squatting on land in Bangladesh, and confrontation politics, tactics known in the histories of both movements.

Finally, Susanna Blankley, a housing organizer and coalition coordinator of Right to Counsel NYC, emphasized that historically the labor and housing movements were not disconnected. “Tenants’ issues are workers issues, workers’ issues are housing issues.” Reactivating the movements as one requires rejecting compromise. “People cut deals because we think we’re going to lose or tick off politicians. This happened in the Mandatory Inclusionary Housing and Jerome Avenue fights.” In bridging the movements, Susanna affirmed that we have to determine what solidarity looks like, eviction defenses, and ways to protect work and neighborhoods. It was especially encouraging to learn about NYC’s rent strikes in the 1800s when tenants who leased farmland where they lived, fought for fair housing and fair work. Their rent strike lasted 20 years! She also uplifted the radical labor movement organizing around the same time in which workers demanded an end to wage exploitation and questioned the existence of wages, which exist to extract profit.

The speakers in this discussion are pushing for reactivated housing and labor movements in which worker and tenant issues are not considered separately. As detailed by Samuel Stein, Marina Ortiz, Julian Brave NoiseCat, Chaumtoli Huq, and Susanna Blankley, the history of both movements have lessons that show radical solidarity. While there is hope for fair labor and fair housing rights to be achieved through organizing, intentional mobilizing, one that is language accessible, is needed for the most marginalized and vulnerable to work and housing displacement.