By Kathleen Clark

I was a first-time felony offender, found guilty of robbery with a firearm, which was actually a flashlight. I was sentenced to 10 years in Florida State Prison, to be followed by 10 years of probation. I had never been involved in the criminal justice system and was totally unprepared for the “long, strange trip” on which I was about to embark.

I started my time at the Land O’ Lakes Jail in Pasco County, Florida. I was a 40-year-old woman who had no previous exposure to the jail or prison system, and now as I reflect, I realize that my life had been very sheltered.

Land O’ Lakes County Jail was a rough ride. I had never witnessed such vagrant acts of inhumanity, disrespect and just plain outright cruel behavior from one human being to another, as I had upon entering the life of the incarcerated, where you cease being a person, and you become just a number. If you have never been incarcerated, you can never even begin to imagine the humiliation and despair that comes with being told to strip naked, squat and cough for the first time. Then, you go through a long demoralizing process being booked in, placed in holding, and sent to a large pod.

The first time I heard the gates closed, I panicked and said, “Hey, I can’t breathe.” The officer said, “You’re talking, so you’re breathing,” and walked away. At that moment, my soul began to die, because I knew no one cared. I no longer counted as a person.

I spent almost 400 days in that county jail and witnessed such an abuse of power and hatefulness that I was slowly becoming numb. My sadness had turned to anger, the anger into hopelessness, and hopelessness into emptiness. That was the condition I was in upon arriving at Lowell Correctional Institution in Ocala, Fla. If I was to get into detail and tell the truth about that place, this story would never end.

I spent two weeks in R and O, which is reception and orientation, on the main compound of Lowell. It was a complete and total culture shock. Just a crazy, filthy place. A rat the size of a cat ran over my foot while I was standing in the chow line waiting to go to breakfast. This was my first morning in prison. When I opened my locker at 5 a.m. to get my clothes, I had roaches running up and down my arm. It was dark because lights didn’t go on until 7, and I have to tell you I was so freaked out. I had never been subjected to anything like this. All I could think about was 10 years of this? No way, man. I just wanted to die.

After two weeks, I was sent to the annex, which was an absolute zoo. Oh, my God, there was so much going on, so many people and rules and officers. It’s like way too much for anyone to even contemplate. Unless you have been there, and lived it, you will never get it. No movie, no reality show, no documentary, no articles, no writings, nothing, will ever fully encompass all the goings on and the insanity that comes with a prison the size of Lowell. Too many inmates, no programs, nothing positive going on ever, no one to lift you up or help you out. Staff is horrendous and predatory in most cases, to be quite honest. And if an inmate doesn’t mind their business and look the other way when an officer is doing something they shouldn’t, well, let’s just say an inmate needs to mind their own business, for their own sake. It’s easy for a female inmate to get lost, hurt, sick, or even dead out of nowhere at Lowell. So yes, every inmate needs to do their time very carefully. It’s known not to upset certain people.

When you first get to prison, you don’t know any of these things. In prison, it takes a certain mindset and a code of behavior to make it. The rules of prison society are different, obviously, than the rules for the outside world. The problem is, when you are sentenced to prison, no one tells you about these rules or how to survive inside. If you are not a quick study, your chances for survival diminish greatly. Those with street smarts have a better chance of making it, because that’s what it takes to make it on the inside.

I spent another two weeks at Lowell, before being transferred down south to Homestead Correctional Institution, a much smaller and aesthetically beautiful compound, full of the beautiful tropical flowers and shrubs that grow so well in South Florida. Homestead had an active recreation area when I was housed there, as well as a few other programs, more than Lowell, but that’s not saying much because Lowell really had no programs.

Homestead had the Ford program and a computer program, but I was told that since I had a 10-year sentence, I wasn’t eligible to take either program. They were geared toward inmates that had five years or less, which meant I was resolved to spending my time playing games at the rec center, perpetrating, a general term both inmates and staff used that refers to inmates doing anything other than what they should be doing. Prison is a large classroom that specializes in the art of criminal behavior and criminal thinking. When there is nothing constructive for people to do, you end up with inmates that spend their time sharing tales of the past—teaching criminal behavior, promoting criminal thinking. After 10 years in the penitentiary, I know more than I ever needed or wanted to know.

Every inmate has a school or job assignment, but after the work day, you do not do much. Every day is a hustle, just trying to get by in prison. It’s a constant routine of breaking rules, trying to get over any way you can. Inmates do whatever is necessary to make the prison system work for them, feeling out officers, sizing them up to see what officers can be worked. This means favors, contraband, sexual favors. And once an officer is marked, anyone that can get in, will get in. Inmates will hustle, con and manipulate. They do this, I believe, because they are bored with a lot of time to do and nothing constructive or positive to do with that time.

I went into the prison system broken, and every day seemed like it was never going to end. I was lonely, sad, beaten down, and I became angrier every day about the injustice of my sentence. So you have thousands of broken women, in a broken system, that receive inadequate medical and mental health treatment. The women in Florida prisons are being warehoused. No rehabilitation, no education, no programs, no help, no nothing. Yet 85 percent will be released back into society, and then what?

My Awakening

In 2006, I was fortunate and blessed to be transferred to Hillsborough Correctional Institution. This was the only faith-based prison in Florida for women. It was a hot commodity, and everyone wanted to go.

But I was not one of those people. I never put a request in to go. I had been incarcerated three years by this time. I had been granted an evidentiary hearing on a post-conviction relief motion and had lost. I knew the reality was there would be no early release. I was returned back to prison from the county jail, where I was facing seven more years of hell. At that time in my life, I had no intentions on doing that time. I made a decision. I wanted to die. I just could not even contemplate how I could do any more time. I felt my life was over. There was no future. I was full of hate, anger, resentments, sadness and a loneliness that I had never felt before, that just made every day seem endless and traumatic.

I had a plan of action to take my life. I felt that was my only relief. However, God had different plans for me. The next thing I knew, I was on the prison bus headed to Hillsborough.

When I stepped off the bus, I knew that something was different about this prison. First, the warden came to the bus and asked each woman if they wanted to be there, since Hillsborough was a voluntary program. If an inmate did not want to be at Hillsborough, they were sent back to the prison from where they came. I did not want to be there and stated that, but again, God had a different plan in mind for me, and I’m humbled and grateful for that, until this very day, 12 years later.

Hillsborough was classified as a faith-based prison, but no one was forced, nor required, to participate in any religious/spiritual-related programs, services or classes. To stay on the compound, though, every inmate was required to take a minimum of one betterment class per cycle, and the cycles of classes were typically six weeks.

That prison was an amazing place. Yes, it was a prison, but it was a place where we were treated with respect, love and even compassion. Not by all, but by many.

I was not a church kind of person. I had issues with a god that I felt allowed me to be sentenced so unjustly when he knew the truth, because, well, he is God.

The chaplain greeted all of us, to orient us to the chapel and what it had to offer. She was such a warm, kind, genuine, loving soul—an absolute rarity to find in prison. By the end of our orientation, all 15 women were crying.

I had been incarcerated for almost four years, and I was accustomed to being screamed at, called every name imaginable. The consensus among staff at the county jail, Lowell, and Homestead was that inmates were garbage, and that is how we were treated.

Chaplain Marchman spoke to us as a group, but the words she said and the message she sent to us was that we were all good people who made poor choices in our lives and ended up in prison. She told us she loved us all, and that she had an open-door policy. Again, this sentiment was unheard of. She made each and every one of us feel a small glimmer of hope, after being treated like a piece of dirt for the past four years. I will admit I was quite skeptical. In the end, Chaplain Marchman was exactly what she portrayed that first day: a wonderful, loving woman of God who fought for every one of us. She was our fiercest ally.

Chaplain Marchman was a hands-on, involved chaplain. She really cared about us and loved us, and she showed us that through her actions. Chap took me under her wing from Day 1. It was not what I wanted, but she was not taking no for an answer.

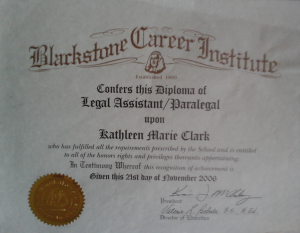

I was assigned to the law library as a law clerk trainee. I was so happy about this. I had developed a penchant for the law through researching my own case and had shared the information with my parents. They paid for me to take a paralegal correspondence course, which I completed, along with the Florida Department of Corrections law clerk training. After nine months of studying and exams, I became a certified law clerk, and my life as an inmate improved vastly.

I loved the challenge of winning a case. I loved helping the other women. And I had a vengeance for justice.

Chap slowly had managed to talk me into coming into the chapel, and I realized it truly was a place for me to just sit and ask God for the strength and the courage to just do this time, get out and live a good life. The programs and classes at Hillsborough were plentiful, and Chap added more classes, different classes, every cycle. She wanted to give all of us the opportunity to get as much as possible to help us learn to live our lives differently, to make choices to better our lives, not destroy them.

Almost 500 volunteers came to Hillsborough daily. We had creative writing classes, life skills, parenting, art class, wellness. We had volunteers that became mentors to anyone who wanted a mentor. I had a wonderful, amazing woman as my mentor for about two years. She would come to see me, and we would just talk. She offered me friendship, love, and acceptance, in addition to offering spiritual counseling, goal setting, and positive decision-making. I am grateful and thankful for that season in my life.

I remember calling my mother, crying, because I had joy. That was not something I had felt in the past four years of my incarceration, or even prior to my incarceration. Maggie taught me the difference between being happy and being joy filled. Happiness is a state of mind. Being joy filled is a state of mind, heart and soul. It is to have a true light beaming from the inside out, and I had it, in prison.

Becoming a certified law clerk. Having a mentor and other volunteers that looked at me with love and acceptance. Getting access to different programs, groups and activities. All of this made my entire life completely different. I was feeling validated, loved, needed, wanted and productive. This was another feeling I had not had in many years, even before prison.

In your “normal” prison setting, you go to work and then hang out on the “yard” just kicking around, wasting day after day, night after night. The existence of programs at the other women’s prison were few and far between. At Lowell, there are so many women that when they would call for church services, everyone wanted to go because there was nothing else to do. The problem was, the chapel couldn’t accommodate even a quarter of the inmates, so they would choose the first 10 women lined up in each dorm. Everyone else was not able to attend.

In the years prior to Hillsborough, I spent a lot of time in confinement. Too much time. I was angry at a system that would sentence a first-time felony offender to 20 years for a robbery with a flashlight that netted $63. I was 40 years old when I committed my crime. I had never had any problems with the law except for a DUI 20 year prior. I had a mental health history, with multiple hospitalizations, for 31 of my 40 years. I was told (incorrectly, I might add) that I wasn’t able to ask for a downward departure, even though I met almost all of the mitigating circumstances and a defendant only needed to meet one. But my charge of armed robbery carried a minimum mandatory of 10 years.

My attorney told me that a judge cannot depart on a minimum mandatory sentence. After becoming a law clerk, I found the statute referencing sentencing and minimum mandatory. It stated clearly that a judge may use his or her discretion when sentencing a defendant in a minimum mandatory situation. Now, in retrospect, I realize the time I received must have been the sentence God wanted for me. At Lowell, I learned the art of perpetrating, manipulating, criminal thinking and every other negative behavior, emotion or characteristic. I took those negatives, bad attitude, anger and depression with me to Homestead, where I learned even more negatives. I witnessed some ugly, hateful, frightening situations. I didn’t care if I lived or died when I first got locked up, so I did what I wanted and never cared about the consequences.

I spent 2 1/2 years at Hillsborough. In that time, strangers lifted me up, loved me, told me I was worthy. They believed in me and taught me to believe in myself. I took at least three different classes every six weeks, and Chap was always adding new ones. I believe there were over 115 different classes offered, all based on faith and character, all geared toward bringing out the best in each woman, and preparing every woman there for a successful free future.

I took advantage of every program Hillsborough offered and felt a renewed hope for my future. I felt alive, and I was joy filled. I became the art room administrator, which brought much more responsibility than I ever was accustomed to having. It felt good to be acknowledged for the growth that was happening in my life. I was involved in everything they had to offer at Hillsborough. I was so busy in the evenings—attending programs, taking betterment classes, church functions, meeting with my mentor—that I often neglected to call home. When my mother asked one time why I had not called in a few days, she was thrilled to hear me say, “Well, Momma, I have a life, too.”

I ended up being shipped back to Lowell due to receiving a disciplinary infraction for smoking. Of course, I was devastated, as were my family, my friends, my mentor, my Chap. I felt like I had let everyone down, including myself.

I wasn’t a model inmate upon returning to Lowell, but I was a certified law clerk and was assigned to the law library, where I was busy and productive every day. My time at Lowell was different this time around. One, I was now a “seasoned inmate.” I knew the rules. Not FDOC rules. But the rules of incarceration. And that is very important.

Two, I was different. Hillsborough had helped me become a woman with a heart and a soul, a woman who had the ability to feel again, a woman who believed in herself and looked forward to a future.

I still had 3 1/2 years to go, but the positive vibe, the reconstruction of my life began at Hillsborough Correctional—through programs, classes, love and acceptance from all the volunteers, being surrounded, for the most part, by positive women that were happy to be rebuilding their lives. I took all that goodness inside of me when I was shipped, and my time spent at Hillsborough carried me through the next four years of my incarceration.

I knew how to feel again, how to love, and how to be loved. I felt like a human being again, and no matter how many times the officers at Lowell called me a stupid ho, a white trash scum, or any other variation of the lovely names they got off on calling us, I never believed it or bought their abusiveness. I had been restored by God, strangers, unconditional love. Being told I was worthy, and feeling as though my life had purpose, my future was not bleak.

I have been free for six years. I was released on 10 years’ probation, which I had terminated after 2 1/2 years, as a pro se litigant, thanks to the incredible experience of being a “jailhouse lawyer.”

I haven’t had any legal issues at all. I held the same job for almost three years until my father passed away, and I moved back to Philadelphia.

Now, I am my mother’s full-time caretaker. She is 85 and has dementia. We moved back to Florida, and I am easing my way back into the workforce and life, while caring for my mother.

I still have issues related to my incarceration and some of the horrific things I witnessed during my time, but I do my best to look at the bright side of life and love and respect every free breath I take. I left a lot of women behind that I love. That was one of the hardest days of my life: to say goodbye to women I respected, loved and considered family, because so many of them will never be on this side, even though they deserve a second chance.

I read about the conditions my girls are living in. It’s so bad. It always was, but now it’s 10 times worse. With the budget cuts and doing away with vocation and betterment programs that they barely had anyway, it’s heart-wrenching.

Inmates are human beings that made mistakes, so they are punished by being sent to prison. That does not mean that they should be treated like animals, denied access to anything that could better their lives, offer them hope, bring them joy, keep them productive, engage their minds, hearts and souls.

I am forever grateful for the time I had at Hillsborough, for all the awesome classes and programs and friendships and opportunities that I was afforded. I question what may have become of my life if I had not been given that opportunity. It is because I spent 2 1/2 years in a faith- and character-based institution that my life was restored, and I have a chance out here. People believed in me and loved me, when I was not able to do either one.

Read how Kathy Carlin, Sadie’s mom and a Florida-based activist, is keeping hope alive during her daughter’s incarceration and how Jan Shelly, a retired attorney, is working with Kathy to fight for prison reform.

Our Community Based News Room (CBNR) publishes the stories of people impacted by law and policy. Do you have a story to share? Please contact us at CBNR here.

Indeed, one should look for the bright side of life. This is very inspiring story and requires a true gut to pass. Everyone deserves a second chance no matter what. Bashar H. Malkawi