Editor’s note: This article is part of “We the Immigrants,” a Community Based News Room (CBNR) series that examines how immigrant communities across the United States are responding to immigration policies. The five-part series is supported by a Solutions Journalism Network Renewing Democracy grant.

By Paul Street and Chaumtoli Huq

“You have to leave the country now that Trump is president.” That’s what Latinx children heard from some white schoolmates in the small southeastern Iowa town of Mount Pleasant in the days after Donald Trump was elected.

“You have to leave the country now that Trump is president.” That’s what Latinx children heard from some white schoolmates in the small southeastern Iowa town of Mount Pleasant in the days after Donald Trump was elected.

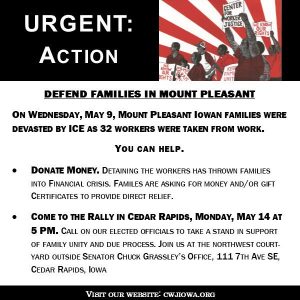

Eighteen months later, the threat of deportation seemed much more real than a schoolyard taunt. On May 9, Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents detained 32 men—22 from Guatemala and the rest from Mexico, El Salvador and Honduras—at Mount Pleasant’s Midwest Precast Concrete (MPC) plant. A concrete mixing plant that started up more than a decade ago, MPC owes its building and success largely to migrant Latino labor, including that of some highly valued supervisors who were swept up.

The raid came out of nowhere, without warning. “They had a canine unit and a helicopter,” arrested MPC worker Nelson Lopez Sanchez told a reporter through a translator. “Some people got beat up. As they were trying to get away, officers used force. Agents were very impolite, making racist comments.” Sanchez came to the United States 14 year ago, fleeing corruption and violence in his native Guatemala.

When college student Juana Barrios learned about the detention of her father, an MPC worker who had worked in the United States for 17 years, it was like living a nightmare. “Scary … the worst feeling I’d ever experienced in my life,” Barrios told an Iowa Public Radio (IPR) interviewer nine days after the raid. “[My father] was our rock, our everything. We need him.”

Other families hit by the raid also were traumatized. Many became afraid to leave their homes. For two days after the raid, 90 children stayed out of school. Three of the detained men were married to U.S. citizens and in the process of becoming citizens themselves. Each of them nonetheless had to put up a $10,000 bond and pay hundreds of dollars for a work permit if they wanted to resume legal employment.

Others among the detained group were asylum seekers fleeing rampant drug violence and government corruption in Guatemala. It’s not illegal to seek asylum in the U.S, and you have to be on U.S. soil in order to apply for asylum here.

Grassroots Emergency Responses Activated

Latinx immigrants together with local and regional allies, responded immediately to defend and support detained workers and their families—to raise bond money and help them “find a way out of this.” Local churches and schools have provided critical caring, sanctuary and sustenance while regional activists have arrived to provide critical legal, counseling and organizing assistance.

Before the raid, Mount Pleasant was home to a local chapter of the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), an immigrant-led organization. LULAC leader David Suarez, a respected community outreach officer for a local bank and journalist, first alerted Mount Pleasant activists of the raid after a fellow Latino community member called him and informed him of a helicopter above and state police on the industrial perimeter.

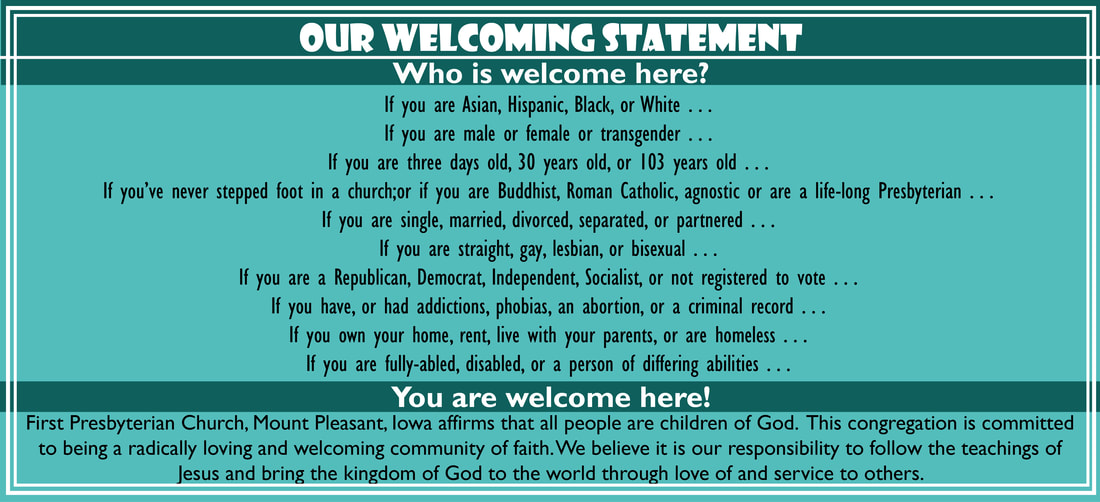

On the day of the raid, LULAC hosted a meeting for families who were impacted, but because they were a brand-new organization, Suarez immediately reached out to First Presbyterian Church (FPC) and IowaWINS (Iowa Welcomes Its Immigrant Neighbors) for support and space. By nightfall after the morning raid, the church was packed with people ready to help.

The Rev. Trey Hegar, the pastor at FPC and a Marine veteran, opposes what he calls “nationalistic politics and theology.” He counters the nativism of local Republicans by quoting Leviticus: “The stranger who resides with you shall … love … as yourself, for you were aliens in the land of Egypt. After Trump was elected, Hegar agreed to make the church an immigrant sanctuary when and if “la migra” (as Latinx immigrants call ICE) arrived. The church would soon become the place where the coalition work coalesced.

ICE actions have a history in Iowa. In 2008, a raid devastated the community of Postsville—which is just 176 miles from Mount Pleasant—sweeping up 20 percent of the town’s population (389 people) and costing the local economy $5 million, according to The Intercept. Grassroots allies already were in place before ICE came to Mount Pleasant. They were prepared.

‘Fighting Back with Solidarity’

FPC is also home to IowaWINS, formed three years ago to support Syrian refugees. After the 2016 elections, the organization shifted its focus to defending local immigrants from Mexico and Central America.

IowaWINS raised $120,000 to pay for rent, groceries, utilities and legal expenses for impacted families. It distributes food and household goods from a pantry at the back of the church. One IowaWINS leader has become the legal guardian of a teenager who lost his sole parent during the raid. Another is a teacher who sees all her students, including the children of immigrants, as “like my own children.” She reports that many of the detained workers’ children are “DACA recipients,” or “Dreamers,” brought to the U.S. “illegally” and residing here on renewable two-year certificates of deferred action.

While support from white allies has been critical, immigrant and Latinx self-defense has been essential. Another early partner was Iowa City’s immigrant-led Center for Worker Justice (CWJ), whose former president, Mazahir Saleh, became the first Sudanese-American to hold an elective office when she won an Iowa City Council race in 2016. CWJ president Rafael Morataya and volunteers came to Mount Pleasant immediately after the raid, contributing translation, organizing experience and ally networks.

“Our success and survival,” the CWJ says, “depends on each other, regardless of where we are born, or what language we grew up speaking. In the face of attacks on immigrant communities, we are fighting back with solidarity. We’ve seen firsthand the destruction that comes from criminalizing immigrant workers. It terrorizes families, gives unscrupulous employers enormous power to intimidate workers, and weakens our entire community. It doesn’t have to be this way.”

Since Trump’s election, the CWJ has trained hundreds of “rapid response,” “family support” and “legal team” volunteers. It will be on hand when ICE conducts another raid in the region. (Hegar reports that ICE agents recently visited the personnel office of a local meatpacking plant in search of undocumented workers.)

In reflecting on the coalition work in an interview with us, Suarez stressed the importance of “working in partnerships. That was key he said in Mount Pleasant. “Individual effort is important, but a unified effort is better.”

Bonding Out As a First Line of Defense

In time, other allies also have stepped up. Volunteers arrived from the University of Iowa (UI) Labor Center, a labor education program that has long advised and advocated for the state’s highly exploited Latinx farm workers. UI law professor Bram Elias brought law students to visit the detainees in jail and to advise the men and their families. Joining the resistance were the American Friends Service Committee, Iowa’s progressive teamsters local, United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW), the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), the Catholic Diocese of Davenport (Iowa), and the Eastern Iowa Community Bond Project (EICBP), which raises funds to get detainees out of jail and into the federal immigration court system before they can be deported.

“What we need to do [first and foremost],” LULAC director Maria Bribesco told Our Quad Cities one day after the raid, “is … pay the bond … so they’re not deported immediately.”

Under the leadership of its co-founder, Natalia Espina, a Chilean-American Iowa City activist and LULAC member, the bond group has played a pivotal role. Paying bonds for the detained workers before they can be removed from the country puts them into a federal immigration court system that is backed up for as long as five years in many cases. This turns folks who were undocumented and living in the shadows into people who are legally safe for as much as half a decade.

The bonds—ranging from $3,500 to $10,000, depending on the immigration violations detainees are charged with—must be paid in person at the regional ICE administrative office in Omaha, Neb., a five-hour drive.

Early legal intervention is imperative, CWJ member Joe Marron reports. In the great majority of cases where detained workers receive rapid legal assistance and bond support, release is achieved.

At this moment, 26 of the 32 MPC workers seized last May have been released on bond. Four have been deported. Two remain behind bars.

Top-Down Raids vs. Bottom-Up Organizing

In Mount Pleasant as in other small towns across the American heartland in 2018, the story has started the same way—literally from the top down—as the Trump administration has re-initiated the high-profile, military-style workplace immigration raids that last occurred under George W. Bush.

The existence of immigrant leaders like Suarez and allies like FPC, Iowa Wins and CWJ were instrumental to the release of the detainees. In other towns, like in O’Neill, Neb., the Aug. 8 raids were a new experience for the community. The topic of immigration had not been discussed among neighbors, which caused the town to be split on the issue.

High school teacher and wrestling coach Bryan Corkle, father of four and a longtime resident of O’Neil, grew up on Rush Limbaugh conservative media. He experienced his own shift on immigration after seeing his immigrant students work hard, get a high school diploma, and unable to find work or continue to college.

“It started with my kids,” Corkle explains. “I fell back on my faith. I was a voice of one, but moving forward, it is changing. Do unto them, as we would want for our ancestors.”

Pastor Brian Loy, who leads the First United Methodist Church in O’Neill and helps run a food bank every week, reported to us that he had lost old high school friends of 30-40 years over his support of laborers.

“Fifty percent of what I knew about immigration was wrong. I was learning as the raid was unfolding.” That’s why he says “we need to educate, educate, educate our communities on immigration.”

The grassroots infrastructure that existed in Mount Pleasant was not yet developed in O’Neil. “We did not have experience responding to raids at the moment, but we relied on statewide groups like Nebraska Appleseed and Center for Rural Affairs,” said Corkle.

Corkle views the faith community as playing a leadership role in protecting immigrants in O’Neill and building support and financial systems for immigrants and their families. This was also true in Mount Pleasant.

In O’Neill, Pastor Loy is working with his church leadership to create an emergency response plan, which he hopes will be distributed to the 1,000-plus Methodist churches in the Kansas and Nebraska areas. This, he hopes, will better prepare other small towns where their churches are located to respond to raids and protect their immigrant congregants. He also is creating an immigration council comprised of impacted families to ensure they are part of the process of coordinating any assistance.

Both Loy and Corkle acknowledge the importance of involving the immigrant communities in humanitarian work and developing their leadership. This approach seems to be key in Mount Pleasant where Suarez and other immigrant leaders have helped bridge the divides between the town. Even there, Suarez shares, they did not have support of 50 percent of the town, but they were successful because they were unified among the remaining 50 percent.

Corkle finds future hope for such leadership in his immigrant students like Stephanie Gonzalez. Stephanie’s mom was among the immigrants detained in the raids in O’Neill and, to this day, remains in detention, leaving Stephanie, 17, a high school senior, and her two younger brothers (elementary school aged and 1 year old, respectively) in the care of her high school friend’s parents.

“I’m scared about my future,” says Stephanie, but “I’m determined to go to college because my mom came here to give me a better life. I want her to be proud of me. When I get my dreams, she will also get hers.”

For now, she is worrying about how to pay for nursing school, in which she has already gained admission and hopes to create an organization after completing her studies that would help families like hers.

Catch-22: Freedom Isn’t Free

There are real limits to what local and regional immigrant rights first responders have been able to achieve for those targeted by ICE. Getting bonded out of detention is one thing. Being able to work legally is another. The 26 “liberated” Mount Pleasant detainees are “stuck in a catch-22,” Hegar admits. Without the right to be gainfully employed in the U.S., many are tempted to “voluntarily self-deport” back to their original home countries. But “if they leave the country prior to receiving an immigration hearing,” Hegar says, “the men forfeit their right to return and risk never being able to see their families again.”

It’s a dark twist on the bumper sticker maxim one commonly sees on the back of pickup trucks in the rural heartland: “Freedom Isn’t Free.”

Hegar sees some of the released detainees’ “heads hanging” as they come into the church’s food pantry. “These guys aren’t takers. They’re workers,” Hegar observes. “The men don’t like relying on charity, their spouses and their older children,” some of whom have had to defer education and careers to take low-paid jobs.

O’Neill has the same urgent need for resources, Pastor Loy says, to help families with rent, food, so that they can stay in the community.

Volunteer psychology students from the university are counseling some of the men in Mount Pleasant on how to process the great blow to their pride and their traditional role as breadwinners.

Some of those detained and released are thinking seriously about returning to the terrible conditions they fled in Central America and Mexico.

“That’s the point of the raids,” Hegar concedes. “To deter immigration.”

Morataya from CWJ wonders “who benefits” from a federal immigration policy that spends millions of taxpayer dollars on terrorizing and devastating families and stripping employers of a highly valued labor supplies. Suarez echoes this point.

“Mount Pleasant is a growing rural economy and needs immigrants,” explains Suarez. “The evidence is in the open jobs that are not being filled.” Suarez reports that Latinx workers perform difficult, dangerous and dirty work tasks (such as animal slaughtering and meatpacking) that white and a growing number of documented African (chiefly Sudanese and Congolese) immigrant workers tend to reject in Iowa—a state that is home, the EICBP reports, to 40,000 undocumented immigrants.

This is not uncommon in other parts of rural America. Corkle, for instance, says that unemployment in O’Neill is 2 percent due to the booming agro-business. “Places like Mount Pleasant and O’Neill are part of a Midwestern regional hub of rural economies, where if you want a job, you can get a job, and so there are no economic reasons to prevent immigration.”

The support detained workers and their families have received in Mount Pleasant and other heartland communities subjected to ICE raids has granted them needed space and time to make deliberate and informed decisions on how best to move forward.

Still, Hegar, Suarez and Morataya say that the nation’s immigration system is “fundamentally broken.” It is in dire need of a “comprehensive reform” that provides a clear and reasonable path to citizenship and removes the constant fear, stigma and insecurity experienced by millions of immigrant workers on whom the nation depends for its economic vitality.

“We need immigration reform as soon as possible” says Suarez. In the meantime, LULAC will continue to help detainees because the immigration process can take a long time. Suarez knows this firsthand: “I am a first-generation immigrant. It took me 10 years and $20,000 to become a U.S. citizen. I know what the families who have no resources are going through.”

Corkle knows what is needed for O’Neill. “I want to see proactive immigration reform to stop this endless cycle of raids.” He believes that a majority of rural Americans agree that the immigration system needs to be fixed, but disagree on how to fix it.

Stephanie see immigration reform as the only solution to unite her family separated by the raids.

Still, Corkle says, “Rural America gets a bad rap as not being welcoming. “What I find lost in the national conversation is that on the far right, they are trying to build the wall, and to the far left, they want to abolish ICE. The oxygen is being taken out for a reasonable position on immigration reform.”

Hegar also worries about the nation’s political silence on the United States’ role in creating the miserable conditions that so many workers and farmer are trying to escape in Mexico and Central America.

Direct service and solidarity are important, but there’s no “way out of this” without effective advocacy for sweeping systemic and policy change.

Detained families in Mount Pleasant, Iowa and ONeill, Nebraska need financial support. To donate to Mount Pleasant families, donate here. To contribute to O’Neill families, donate here.

Paul Street is an independent journalist based in Iowa City, Iowa. Chaumtoli Huq is the Editor of Law@theMargins.

Our Community Based News Room publishes the stories of people impacted by law and policy. Do you have a story to tell? Please contact us at CBNR. To support our Community Based News Room, please donate here.

[…] Paul Street and Chaumtoli Huq Law at the Margins […]