As U.S.-Iran government relations intensify, communities in both countries are promoting the shared human story — to expose people to true Iranian culture and dispel myths.

By Carla Pineda

On a recent Saturday morning, the Pink Orchid is buzzing with a steady flow of customers in the heart of Tehrangeles — a nickname for the most prominent Iranian enclave outside of Iran, located in the Los Angeles neighborhood of Westwood. Some customers pop by to pick up Persian cream-filled donuts and shirini morabaii jam cookies for their parties, while others sit down to enjoy a slow lunch. Friends catch up on gossip over Persian tea and others crack open a book in the corner.

On the surface, Iranians appear to be leading normal lives amid escalating political tensions between the United States and Iran. But a skewed definition of “normal” is leaving its mark on the Iranian community in both countries.

In the U.S., sanctions have created hardship for Iranians with family living in Iran. They aren’t allowed to wire money to relatives. They worry that specialized medication is scarce in Iranian hospitals. And communication systems in Iran are unstable, as major U.S. tech companies have been ordered to cease operations in the country. The impact of tension and anti-immigrant sentiment trickles down to their everyday life in the U.S. as well, according to Persis Karim, director at the Center for Iranian Diaspora Studies at San Francisco State University.

“For Iranians, some of the most profound issues are family separation and a real, general anxiety about war,” Karim says. “Iranians in the U.S. … are afraid to travel outside the U.S. out of fear they won’t be allowed back.”

This fear extends across a wide spectrum of socioeconomic standings, including celebrities like popular Persian vocalist Googoosh. The singer lives in Los Angeles and is a green card holder, yet when the Muslim ban was implemented in 2017, she expressed concern about flying back home from London.

“I can say I had exactly the same feeling 37 years ago in 1980 when I traveled to Tehran from London, and I was expecting some unpleasant events,” Googoosh said in an interview with Euronews. “And my expectations became a reality.”

‘Living a War’

On the other side of the world, in Tehran (7,567 miles from Los Angeles), anthropologist Alex Shams and another 12 million-14 million Tehran residents also stop by bakeries, spend time with friends on weekends and lead a city life much in the same way as Tehrangelenos.

In Iran, however, people are feeling the brunt of an economy that is contracting quickly. People, particularly wealthy Iranians, still dine at restaurants but not as often as they would like due to economic pressure on both consumers and small-business owners. People still go to the bakery, but the price of bread and other staples has skyrocketed due to record-breaking inflation. People talk about the conflict brewing between the U.S. and Iran constantly because it touches every aspect of their lives.

“We’re already living a war,” Shams says. “When you have an economy engineered by another country to be destroyed — which is what sanctions are — that’s a form of silent warfare against an entire nation of 80 million people.”

Shams says sanctions disrupt the way people perform many everyday activities, such as purchasing plane tickets or downloading apps on their phones. As a U.S. citizen born in Los Angeles but now living in Iran doing research, he has a unique perspective on how U.S. sanctions have impacted the people of Iran for decades.

“Being in this country was both foreign and so familiar in so many ways,” he says. “I was accepted as part of a family, even though I wasn’t from there. Not only was this a foreign country — it was also public enemy number one.”

Shams recalls visiting his father’s family when he was a child and the concerns that he carried with him whenever he landed on U.S. soil.

“The amount of pistachios you could bring back was regulated by law,” he remembers. “The number of carpets you could bring back was regulated by law.”

As Shams grew older, his concerns grew as well. On a trip back to Iran, he packed cancer treatments in his luggage to supply Iranian hospitals that were all out. “It’s crazy to put [medication] in a duffel bag and carry it with you,” he says. “At one point they asked us to bring ibuprofen because they were having shortages of the most basic kinds of painkillers.”

While medicine is exempt from the current round of sanctions, the challenge hospitals encounter is the same obstacle that prevented Shams from wiring money to his grandmother when he was in the U.S. “If Iranians are banned from accessing the global banking system, including credit cards, they can’t buy anything online. They can’t pay for imports,” Shams explains. “So hospitals don’t have a legal way to pay for medications.”

Though sanctions have intensified in recent years, conflict and economic instability are nothing new to Iranians, shares Alireza Hekmatshoar, program director at Radio Iran KIRN in Los Angeles.

“Everything now is 10 times more expensive,” Hekmatshoar says. “But it seems that life is going on.”

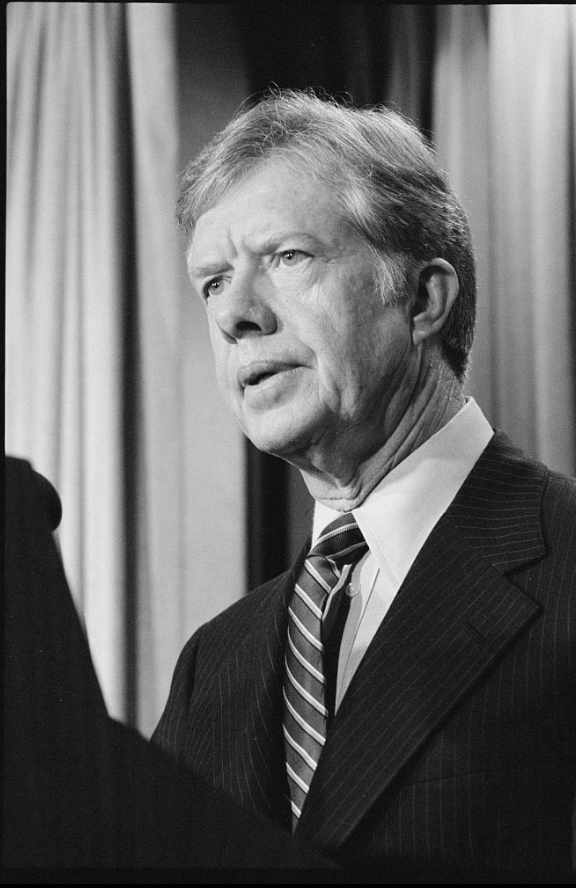

Iranians have lived under U.S. sanctions since Jimmy Carter first imposed them in 1980. What followed was decades of tumultuous relations between the two countries, and between Iran and U.S. allies. “So people got used to it,” Hekmatshoar says.

Sanctions reached their pre-Trump peak under President Barack Obama, shutting down nearly all trade with Iran, and “weakening the middle class and marginalizing the democratic voices,” according to Iranian-American filmmaker Beheshteh Farshneshani.

But Obama loosened restrictions when the two nations struck a nuclear deal in 2015. It was like a breath of fresh air, Shams recalls. The deal symbolized a shift in how the world perceived Iran and how Iran engaged with the world. The country’s economy was infused with optimism, young people started opening new businesses and tourism started booming.

“Suddenly, with the nuclear deal, it felt like there was actually hope for peace and engagement,” Shams says.

All signs of economic revitalization started unraveling quickly, however, when President Donald Trump took office in the U.S. A short seven days after his inauguration, he set the tone for the new administration’s approach toward immigrants by announcing the Muslim ban, prohibiting citizens of seven Muslim nations, including Iran, from entering the U.S.

A year later, he announced U.S. withdrawal from the 2015 nuclear deal. He reinstated existing sanctions and has imposed new ones since. In addition to petroleum, the U.S. bans the trade of many Iranian goods, including handwoven carpets, automobiles, caviar, and pistachios, designating any country trading with Iran an enemy of the state.

Uniting a Divided Community

Hekmatshoar sees a clear division within his audience when it comes to U.S.-Iran relations: conservative Iranians opposed to the existing regime in Iran, whom he dubs “Trumpicans,” and those opposed to sanctions.

“Trumpicans are Iranian conservatives that don’t accept any criticism about the president [Trump],” Hekmatshoar says. “Even if it’s obvious that he did wrong, they will not accept that.”

With a large majority of his listeners being conservative Iranians, one of his largest challenges at the radio station is maintaining balance in his programming.

“The people with the megaphones are the most reactionary and conservative people,” Shams says. “They are bitter about their experience, and they took all the wrong lessons.”

Amir, who requested his last name be withheld, is partial owner of a family-run Persian grocery store in Los Angeles. He identifies as Iranian-American. Despite expressing general humanitarian concern for the people of Iran, he hints at faint support for sanctions against Iran’s leadership, remembering the pain this government inflicted on his family 40 years ago.

His parents fled their country after the U.S. orchestrated a coup to overthrow Iran’s monarchy, leading to the 1979 Iranian Revolution. The Islamic Republic took over, suppressing women’s rights, enforcing strict dress codes and persecuting the Western-educated elite.

Facing violence, many Iranians fled to Los Angeles and other U.S. cities. But once there, they met the backlash of the Iran hostage crisis, in which Iranian students took 52 hostages at the U.S. embassy in Tehran for 444 days to protest American presence in the country. Many Iranians had trouble finding jobs and were discriminated against for years in the U.S.

“That really traumatized a generation of people, and it made them afraid of politics,” Shams says. “It made them afraid to speak their minds. It made them encourage their children to keep their heads down and not get involved.”

But this fear does not justify punishing the Iranian people today, he says.

“I find [this support for sanctions] completely unconscionable and so deeply offensive with every bone in my body, as someone whose family lives here [in Iran] and someone who understands that Iranians living in Iran are human just like the rest of us,” Shams says.

Shams is part of a wave of Iranian-Americans standing up against conflict.

“Whether it’s the Muslim ban targeting Iranians, or sanctions preventing Iranians from having relationships with their families in Iran … these are all things Iranian-Americans are waking up to,” Shams says.

With a glimmer of hope, Karim says the Iranian community in the U.S. is in a stage of transition, as they learn that keeping their head down has not made them invisible nor immune to anti-immigrant measures.

“The hostility toward all immigrants has not escaped Iranians,” Karim says. “It doesn’t matter how successful they are or how much money they have. We’re seeing that passing in this realm of whiteness doesn’t really exist.”

With second and third generations of Iranian-Americans representing an integrated culture, Iranian-Americans have a strong sense of belonging to the U.S. and are resisting against any policy intended to remove them.

“Their loyalty is not to Iran,” Karim explains. “Their loyalty is to this country, so they want to fight for their rights in this country.

When the Muslim ban was implemented, thousands of protesters flooded airports to demonstrate and aid travelers who were caught in the limbo of this policy. Attorney Elica Vafaie, president of the Northern California chapter of the Iranian American Bar Association, was one of them. She provided emergency legal services to families at San Francisco International Airport and worked on policy to fight the ban. In an interview with Karim, she said she initially decided to focus on immigration law and human rights when she saw thousands of people added to deportation lists under the “special registration” system simply due to their ethnicity, race and religion.

Seeing the Human Story

As Iranian-Americans fight on the legal front, organizing to influence national immigration policy, they also are placing a heavy emphasis on cultural preservation and exposing Americans to Iranian heritage. For example, Iranian visual artists have received well-deserved attention in major U.S. cities, such as New York City, Chicago and San Francisco, Karim says.

“Iranians care deeply about culture and art,” Karim says.” It’s sort of an anchor for who they are. It’s also their anchor for remembering themselves in this U.S. context.”

Karim teaches courses on Iranian film and literature, among many personal endeavors to promote cultural exchange. With the Center for Iranian Diaspora Studies, she work to offer a counternarrative, challenging anti-Middle Eastern and Islamophobic rhetoric with research, teaching and programming about the global Iranian experience.

Karim is currently co-directing “We Are Here,” a documentary telling personal stories of how Iranians have arrived and settled in the San Francisco Bay Area for generations. The ultimate goal of the film, partially funded by the Nasiri Foundation and co-produced by San Francisco State University’s Documentary Film Institute, is to convey the community’s resilience despite the political tension that has cast a shadow over Iranian-Americans for decades.

“Whenever the rhetoric stays at the tension between the governments, the human story is lost,” Karim says.

To preserve this humanity, the Center for Iranian Diaspora Studies is establishing a digital archive of photographs, oral histories and historical documents to catalog the growth and contributions of the Iranian-American community. The project is an urgent effort because it could serve as the only archive of the Iranian diaspora’s history. Many Iranians have not shared their stories due to fear of being targeted, and Karim hopes to collect as many of those stories before they are lost along with older generations.

The nonprofit organization Diaspora Arts Connection is also committed to opening a window to different cultures in the U.S. The group’s annual performance “Let Her Sing” is dedicated to celebrating the female voice, which is suppressed and censored in parts of the world, including Iran. The event provides a safe space and captive audience for women who are forbidden from performing in front of a live and mixed-gender audience in their own countries.

In a more accessible form, the Instagram page “This Iranian American Life,” highlights everyday moments of Iranian-Americans. The page is open to submissions, giving people the opportunity for self-representation.

Hekmatshoar tries to create a safe haven for Iranian culture over his airwaves. By participating in cultural events, such as an annual celebration of Norouz (Persian New Year), and encouraging his audience to engage in civic activities, including the upcoming census, his team strives to distribute unbiased information and share cultural knowledge with younger Iranian-Americans.

“At this station, we are working hard to keep the community together, to keep the culture [and] to keep the language alive,” he says.

Similarly, Shams was drawn to anthropology to understand people and see the world through their eyes. In his quest to produce knowledge about Iran and dispel stereotypes about its people, he hopes to help Americans appreciate the many similarities they have with Iranians.

“There’s always more commonalities than there are differences,” Shams recognizes. “It just takes having a conversation.”

Food also offers a great bridge for Iranian Americans to both immerse themselves in their culture and share it with others. Hanif Sadr, owner of a northern Iranian kitchen/catering company called Komaaj, hosts a pop-up kitchen and serves his food at a cafe in North Berkeley. Sadr is sharing his heritage with Americans, andalso fellow Iranians, who are not familiar with northern Iranian food. He came to the U.S. seeking to study engineering and quickly realized how much he loved cooking.

Sadr represents a cultural response to anti-Iranian sentiment, but he also portrays the impact of the Muslim ban and of sanctions. He is currently separated from his fiancee, who has not been able to obtain a visa to join Sadr in the U.S.

While culture is an invaluable resource and is the only thing that can change people’s hearts, its effectiveness in combatting negative news media and racist policy is weak, admits Karim.

“I wish I could say culture is winning, but it’s not,” she says.

For example, the production of cultural programming becomes increasingly difficult as Iranians around the world face unprecedented obstacles in obtaining U.S. visas. Access to Iranian cinema is diminishing as the Iranian government cuts arts funding and sanctions make it difficult to distribute films abroad. Cuts to arts funding in the U.S. don’t help either. This restriction, what Karim calls a chokehold of culture, is sometimes created by design, she says.

“Culture is always under siege in time of conflict,” Karim says. “When people see with their own eyes, or experience through their own taste buds, or hear evocative music, or see films from Iran… they see the human side.”

Dialogue and cultural responses alone will not change policy or end sanctions. But they are steps in that direction.

“We have to hang on to [culture] as one really invaluable opportunity for people to walk in the shoes of fellow humans,” Karim says. “But it’s not an easy thing to do when the airwaves are controlled by a different narrative.”

Karim shares an anecdote that is reminiscent of a Saturday at the Pink Orchid in Los Angeles. During an interview for the documentary “We Are Here,” her co-director Soumyaa K. Behrens mused at the tea and the beautiful fruit and pastry spread assembled by their hosts.

“They always feed you,” Behrens said.

Unsurprised, Karim explained this is simply part of a deep Iranian culture of hospitality.

“I think that’s the stuff that never gets seen, the everyday stories of people’s lives, the resilience, their generosity, their ability to reinvent themselves,” Karim says. “But also their ability to share things about their culture that are deeply important to them.”

All of the stuff that makes us human.

Carla Pineda is a digital producer at KCET and PBS SoCal in Southern California.

Community Based News Room publishes the stories of people impacted by injustice and aspiring for change. Do you have a story to tell? Please contact us at CBNR. To support our Community Based News Room, please donate here.

[…] Carla Pineda This story was produced by Community Based News Room, a project of Law of […]