Failing to move to virtual court proceedings compound the impacts of poverty and COVID-19.

By: Alanna Wade

US Courts are continuing to put the most disadvantaged people needlessly at risk of contracting Covid-19 by requiring in-person proceedings. Several jurisdictions, including New York, have resumed this policy, even though the majority of appearances are for minor matters such as status updates and ordinance violations, which could easily be postponed to a later date without harming the parties. A federal judge in New York City recently denied requests for temporary restraining orders to pause in-court proceedings. Public defender organization argue that this will discriminate against the disabled. In addition, poor, elderly, and minority communities have been the worst-impacted groups since the beginning of the pandemic. They are also the most likely to be called into court and the least likely to have health insurance. The United States has the technological capability and much of the requisite infrastructure to conduct remote hearings, and although some jurisdictions quickly adopted this idea, most have not, and there seems to be no rational basis for these decisions.

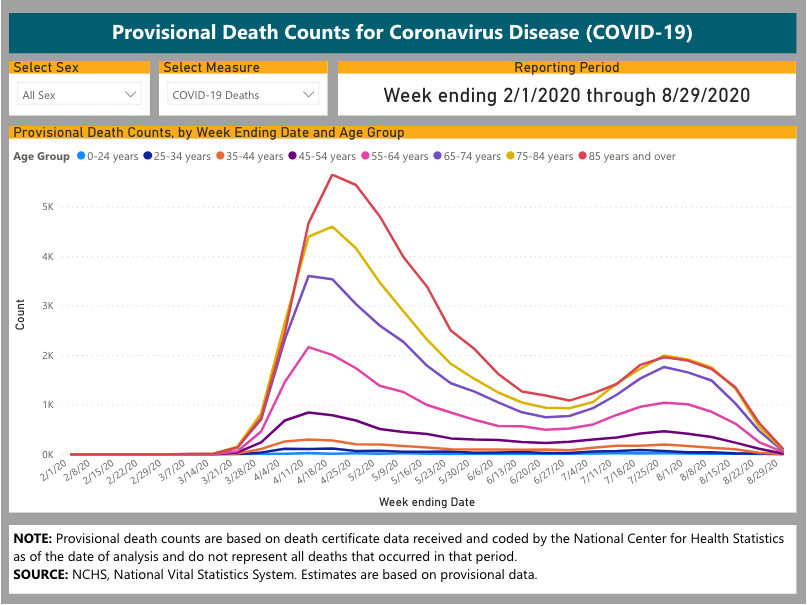

Low-income and minority communities have been horribly impacted by Covid-19, and it is no coincidence that the same individuals are seen most in the courts. Poverty and lack of financial resources are major factors both in the justice system and in one’s likelihood of contracting the virus. The risks are compounding. In the face of this pandemic, disadvantaged communities are often forced to continue working, having been deemed “essential,” often without proper personal protective equipment (“PPE”) or hazard pay. Many essential workers are at or below the poverty line and work for companies that do not provide health insurance. We find ourselves living in a world where, despite individuals being deemed essential, they are not worthy of even the smallest wage increase or healthcare coverage.

These same individuals are now being forced to enter physical courtrooms. In Tennessee, jury trials were still suspended until July 3, but each district will be allowed to resume other proceedings as long as they file a safety plan with the Supreme Court. States like Kentucky and Iowa are lifting the in-person restrictions, while judges in Georgia courts are testing positive for the virus. Those in poverty typically lack the financial resources to hire an attorney for simple requests like postponements of a court date. In addition, most people are unfamiliar with court procedures and how to request a continuance without assistance. These communities are unable to advocate for themselves during such a dangerous time. Even in instances where individuals find representation, some judges have declined to postpone their dates simply due to Covid-19. By doing this, judges have forced people into potentially life-threatening situations.

The United States has the technological capability and much of the requisite infrastructure to conduct remote hearings, and although some jurisdictions quickly adopted this idea, most have not, and there seems to be no rational basis for these decisions.

The pandemic has left many to make difficult choices, but for the individuals called into court, they do not have the choice to skip out. People are being forced to risk their lives at the behest of judges, many who do not see the gravity of the situation or claim there are constitutional issues present when postponing dates or using remote court. No one should be placed in a situation where they must risk their wellbeing for a legal requirement that could easily be satisfied virtually.

Several disability rights activists and groups assert that judges forcing in-person appearances are actually breaking the law. Advocates and attorneys have requested that judges provide reasonable accommodations for their at-risk clients during the pandemic, only to be denied. This is likely in violation of Title I of the Americans with Disabilities Act which states that various entities, such as employers and public services, must make reasonable accommodations for their applicants and employees. During a pandemic, many disabled individuals are at a higher risk for contracting Covid-19, potentially suffering far-worse effects than the general population. Under the ADA, the courts have a duty to provide a “reasonable accommodation” to keep them safe from this new risk to their health. Most agree that a reasonable accommodation would be to relieve at-risk individuals of their duty to attend court in-person and institute remote court proceedings; unfortunately, many judges have not agreed.

The risks associated with contracting Covid-19 do not start and stop at living or dying

Social Security proceedings have been more prepared than many of the other courts to handle this situation. In March, the Social Security Administration announced that all participants in disability hearings would be appearing telephonically. Social Security had already been set up to do video hearings with attorneys and claimants appearing remotely, for years. Disability attorney, W. Christopher Freiberg, told Law@theMargins, “Before the pandemic, I had occasionally had cases where claimants were given permission to appear by telephone, but I had never done a hearing telephonically. I would say that overall telephone hearings are doable, but not ideal. Things work correctly 99% of the time, but there are some hearings where we just can’t get everyone connected or calls keep dropping. Judges have been pretty understanding about this though, and if clients really want an in-person hearing, they have an option to postpone their case until those are available, but as of right now, we don’t know when that will be. At one time, I was hearing we would go back to in-person hearings in October. Now, I’m hearing it will be next year. My guess is that we won’t be back to live hearings until Spring or Summer of 2021.”

Contracting an illness that may be life-threatening or present a lifetime of medical complications certainly seems to fall within the “undue burden” category. Some may wonder why social distancing in the courtroom might not fall within the realm of reasonable accommodation. Even when considering average, healthy individuals, the courts can hardly provide any sense of safety. This is because courtrooms are not built for social distancing. The court system and its antiquated rules are not prepared for mask-wearing witnesses. A New York Time article describes some of these complications: “Mr. Potter said he and his client had to confer so frequently that it was impractical to don masks, so they ended up getting much closer than health experts recommend. And there were other issues: Because the jury box could accommodate only three people, the rest of the jury was spread out behind Mr. Potter, where he could not see their reactions or be certain that they could see and hear the proceedings.” The bottom line is that many of the courts are demanding that the impoverished and other high-risk communities put themselves in harm’s way, yet again, but for what? Is it right to ask a witness to unmask themselves even when that presents a real risk to everyone within 8’ of them? Will people contract Covid-19 in court and end up on disability for the rest of their lives due to severe and permanent lung damage or stroke?

People are being forced to risk their lives at the behest of judges

Recent developments have shown that although the death rate may be lower than what was expected, definitions and depictions of “recovered patients” from Covid-19 are not accurate portrayals. The term “recovered” in most instances, simply means the individual did not die. What many do not realize is that those who “recovered” are often left with permanent lung damage, and will likely never return to their life as it was before they contracted the virus. In addition, many individuals who were otherwise unaffected may suffer from acute ischemic strokes and large vessel occlusions. Many victims of these types of strokes are the very young, which was almost unheard of prior to the Covid-19 pandemic. Coupled with the fact that so many Americans do not have health insurance, the big picture is absolutely devastating. The courts may cause individuals to become permanently impaired. Some of these injured people will likely have to rely on the state to support them. This is an effect that will be felt, not felt only by the injured party, but by all the taxpayers. Several victims of Covid-19 have amassed hospital bills amounting to over a million dollars, and that number does not include continuing care. The risks associated with contracting Covid-19 do not start and stop at living or dying, that is why it is so important to minimize exposure wherever possible, and the best way for the courts to do this is to institute remote court proceedings. The negative health effects can be felt for a lifetime and the cost will ultimately fall upon the American taxpayers when this is over.

There are a variety of valid concerns presented where remote court proceedings are considered. Constitutional issues may be brought; security and privacy are always a concern; there is a lack of control over the environment; many of the elderly and poor do not have access to internet or a computer and some cannot operate a computer or use zoom. Witness tampering and corruption are major considerations, and there is also the dehumanization factor. So far, dehumanization has not been mentioned in regard to remote court, however in the past, it has played a major role in other remote operations, like the use of UAVs (drones), and it has even been brought up in recent years as a major concern with pornography. Dehumanization of a defendant in a serious criminal trial could have potentially devastating effects, but what everyone seems to forget in these discussions is that not every court proceeding is a trial. Not every appearance is to testify for a murder. The majority of appearances are for minor matters such as status updates and ordinance violations that could easily be postponed to a later date without harming the parties. Is this what we are risking people’s lives for?