By Carrington Keys

Editor’s note: Carrington Keys was one of six black men known as the Dallas 6. They were inmates at the State Correctional Institution—Dallas (SCI Dallas) in Dallas, Pa., who blew the whistle on prison staff brutality and took nonviolent action to stop the abuse. After being incarcerated for over 19 years and spending a decade in solitary confinement, Keys was released from prison on May 15, 2018.

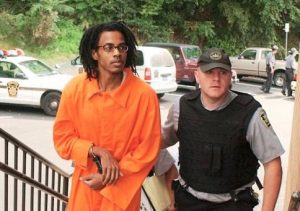

[dropcap]I[/dropcap] was arrested on March 23, 1999, in Pittsburgh after being accused of attempting to commit armed robbery against a bar full of patrons. After being arrested, I was charged with other robberies which occurred in the same week. This led to a 20-year conviction in April 2000.At the time of my arrest, I was a teenager with no sense of self. I did not know my purpose in life. However, in that dark place called prison, I found myself and decided to grow. Malcolm X said that prison is a wise man’s university and a fool’s playground. I chose to make it my university.

When I entered the prison system, I had to learn fast to come to terms with the harsh realities of prison life. I lacked any direction, identity and vision for myself and the future. With the help of my mother Shandre Delaney and a counselor named Don Shipley, I began to receive literature that helped me see where I fit in this world.

From there, I began my journey of self-knowledge and self-discovery. As my eyes started to open, I began to make the connections between the current prison system and the former system of chattel plantation slavery

The journey started at 19 after I was placed into the state penal system of Pennsylvania. I was taken to Western Penitentiary in Pittsburgh, and as I entered the prison, it looked and felt like I was walking into a slave plantation. It appeared to be nothing more than a slave plantation with a fence around it.

Days later, I was transported to a different prison, Camp Hill. During transport, the officer talked to me and other imprisoned men like we were less than human. I spoke up to let him know that although I am incarcerated, I still am a human being worthy of respect. This speech was to no avail, and the prison guard believed that I was supposed to tolerate his disrespect as a natural virtue of my incarceration.

After I arrived at the next prison, I was mistaken for a juvenile (17 years old or younger) and thrown into a juvenile holding cell. I was later pulled out of the juvenile holding cell and threatened by a female secretary. The woman told me that this was not a juvenile facility and that they knew how to deal with people like me at Camp Hill. I never forgot the woman’s face. Years later, she became a warden at State Correctional Institution-Rockview (SCI Rockview), a prison near Penn State University.

On the same day of my arrival, a Hispanic officer gave me a tour of the prison. He introduced me to a prisoner who had the same sentence as me. The prisoner told me that he was maxing out his 20-year sentence the next day and that he had been at Camp Hill before the riots on Oct. 25, 1989. Maxing out is when you serve your entire sentence behind bars. The prisoner warned me not to stay at Camp Hill because I would max out if I did.

After this tour, I was walked into a hallway that (I did not know at the time) led to the hole, or the restricted housing unit, solitary confinement. A door opened, and a lead officer and two giant officers with sticks were waiting for me. The lead officer told me to get against the wall and not make a move, or they would bust my head open. (He is now a high-ranking officer at SCI Forest.) I was then taken to a cage and stripped naked and examined like a slave on an auction block. After being inspected like an article of property, the officer gave me a black-and-white-striped uniform like the ones in the old prison movies.

Solitary confinement at Camp Hill, also known as Camp Hell, was horrendous. The block was infested with mice and huge flying cockroaches. At night, the mice would crawl out of the vents under the sink looking for crumbs. I witnessed officers run a prisoner through the cell block butt naked in handcuffs as a form of psychological abuse and humiliation. That was my first lesson. There are serious consequences for prisoners who speak their minds.

I later learned to study a big handbook of prison policies and prisoner’s rights, which gave instructions on how to file grievances and the limitations placed upon the prison administration by the courts and legislators. I learned that grievances are the best means of defense against officers and their supervisors. Direct confrontation or verbal engagement only leads to trouble.

I learned that prison administrators have a code of ethics and professional responsibility that sounds good in theory but is not practiced. After repeatedly being placed in solitary confinement, I decided to study law to defend myself against the reprisals I faced for being outspoken.

I also learned not to be a reactionary and did not respond to every disrespectful and demeaning remark.

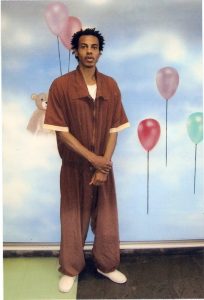

The restricted housing unit is a gruesome environment. I spent over 10 years in solitary confinement, and my experience was crucial in shaping me into the person that I am now.

What was solitary confinement like day by day?

I was living a nightmare, which I am sure devious minds designed. First, upon entering the restrictive housing unit, every inmate is stripped naked and told to lift their private parts, bend over and cough. This process is often repeated more than once, abused and used excessively.

During my three-year stint at Camp Hill’s Special Management Unit, I was subject to many forms of abuse. For one whole year, I refused to respond verbally to the constant harassment and deprivation. The officers did everything to break my spirit—from food deprivations, denial of yard, and showers off and on sometimes for months at a time. They even destroyed family photographs and other personal belongings.

When I refused to react violently, they resorted to abusing the stripping process. Every time that prisoners leave their cell, they are told to strip. Every time a prisoner leaves and returns from law library, he or she is forced to strip for humiliation purposes. Because I had court orders for law library, the officers couldn’t deprive me of it. They resorted to other means—telling me to strip over and over—to discourage me from coming out of the cell for library.

At that point, I just about lost it and told them all about themselves. I refused any further search, and the officers went and got a gang of other officers. They were bent on attacking me physically by holding me down and restraining me. I knew how that would end, so I used my head and complied for the strip search. They wanted the opportunity to pepper spray and beat me down, but they were denied. I was then given misconduct reports for refusing to obey an order.

In the restricted housing unit, or RHU, prisoners are let out of the cell once a day for one hour and placed into a dog cage outside for exercise. The cage is not much bigger than the cell, which is about the size of a McDonald’s bathroom. The cages are like the ones you see at an animal shelter or zoo. In the yard, you can be caged next to anyone, just as in the hole itself. A large number of mental patients scream and make noise all night. Most of my 10 years in the hole had no access to televisions or radios.

When I first entered the system nearly two decades ago, inmates in lockup weren’t allowed access to personal books or magazines, only the Bible and Quran. The day consisted of few activities. In the morning was yard time for one hour, followed by a 10-minute shower. In between was meal time, and mail got passed out at night.

Prisoners in the hole were only allowed to retain 10 pictures, and any books or additional pictures would go to your property. Books and other belongings were stored in a property room. After years of jailhouse lawyers challenging the policies as arbitrary and unreasonable, the book and magazine policies were changed.

Still, in the hole, prison guards control an inmate’s every activity—his or her entire livelihood. Guards regulate every move. They decide if you will eat, exercise, shower, and receive mail. Prison guards can make your mail disappear to the trash can, or they can starve you for weeks, mark it as a refusal, and act as if it never happened.

Prisoners are forced to band together to survive. If you are on a housing unit with experienced and resourceful prisoners, your chances for surviving mentally, spiritually and physically are good. This is how the Dallas 6 took a stand despite knowing the consequences of our actions.

I survived by exercising every day, and through studying useful subjects in body and mind disciplines such as tai chi chuan. I also fasted and practiced meditation. Good dialogue with critical thinkers and mail from family helped me to stay grounded. I wrote books about motivational thinking. I began taking a course for paralegal studies. However the prison restricted me from completing this degree, which required a school official to proctor my semester exams.

The prison officials only gave me respect after fighting them in court and refusing to give up or allow them to break my spirit. Prison officials hate being pulled into court for questioning before a judge or jury, and they will think twice after you show them how far you are willing to go. From teenager to adulthood—spending all my twenties and most of my thirties behind the walls of Pennsylvania’s most harsh dungeons—I’ve learned to channel my energies into positive, productive work.

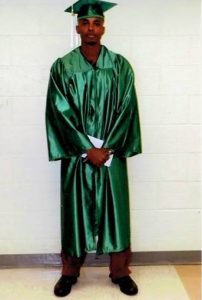

Over the years, I wrote books about correcting criminal thinking and using street smarts to prosper legitimately in the world of business. While in solitary confinement, I took college courses for paralegal training, and classes for banking and financial management. After leaving solitary confinement, I received certifications in fiber optics, HVAC, electricity and masonry.

I made a decision. Although I was being held captive against my will, I would make sure that I returned to society as an asset to my community and not a liability.

I plan to start a program for at-risk youth to help them discover their passions and push them to think outside the box, so they can get to know who they really are as individuals and not what society tells them they are. After speaking with many young men in prison, I realized that we all have something in common. The public school system does not teach us positive ideas about people of color, and this creates a lack of self-esteem and self-worth.

I plan to be involved in programs that counter the poison systemically infecting the minds of the youth, disadvantaged, poor and people of color. Everyone wants to feel like they matter. We live in a society that teaches subconscious, subliminal and subtle racism. It’s one thing to tell America and the rest of the world that “all Americans are equal, hence all lives matter.” However, it’s another thing to show us every day in court, in school, in shopping malls and in the streets that the lives of people of color “don’t matter.”

One group is favored over every other group at every level of society. It does not matter if the Pledge of Allegiance says “one nation under God.” The people do not see this so-called “oneness.” Subconscious and subliminal racism is more dangerous than blatant and open racism. Every child exposed to this quiet weapon suffers. Constant exposure to an unequal educational and political system—conveying “all Americans are equal” in one breath, but “some Americans are more equal than others” in another—does unquestionable harm.

All year round, the school system teaches about the great accomplishments of European discoverers while minimizing the contributions of all other people. For one short month, certain people are mentioned and given bare-minimum recognition. Such teachings place the seeds in every child’s mind that white is great and everyone else is an underachiever. This type of indoctrination is unhealthy and dangerous. For me, when I finally learned some real history about achievements of people of color, a light bulb turned on in my mind. But I was already behind the walls of the colony.

When I’m free, I plan to speak at colleges and universities about my experiences inside the system. I’m also working on getting one of my books about my life published. It contains essays about the Dallas 6 case and my experiences in solitary confinement.

I have learned a lot about justice, standing up for human rights, the power of people, protest and resistance. For the poor and disadvantaged of society, justice is not automatic. The system is set up in a way to do the exact opposite of what it professes to do. Justice is just for those powerful enough to receive it and those rich enough to afford to pay for it. You will either pay for it in money, sweat, labor or blood—but justice will come at a price. The truth is the sword of justice that cuts through the lies of corrupt prosecutors and bad-apple police officers.

Standing up for human rights is something everyone should do because human rights apply to everyone. If one person’s human rights are in jeopardy, everyone’s human rights are in jeopardy. If everyone viewed an attack on others human rights as an attack on their own human rights, we would see more compassion in this world.

I’ve learned that peaceful protest and resistance can have far-reaching impact, much farther than the moment itself. I’ve learned that protest and resistance may be the only thing that prevents another’s death.

Sometimes, one has to commit a lesser offense in order to prevent an even greater offense. Sometimes, you have to stand up even if it means breaking your leg in the process.

In America, dissent is our right. People have died in order for me to express the right to dissent under the First Amendment of the United States Constitution. One of my comrades likes to say, “Freedom of speech ain’t shit if you’re not talking about anything.” In other words, when you have a voice, why not use it to say something meaningful?

It takes courage to stand up to injustice, but unity is more powerful than all the bombs in the world. An old African proverb says unity is strength and division is weakness.

The Dallas 6 trial of April 4, 2016, is proof of the strength of unity. We stuck to our guns in unity and overcame riot charges. In the face of decades of more prison time, we stood together and crushed the lies of a powerful state prosecutor.

I would encourage others to use their voice in every available platform—whether it is politics, social media or protest in the streets—to bring about the change that you want to see in the world. It will be not be easy, but one way to get started is to search for commonalities amongst people and not differences. Learn from others who have different experiences than your own and share their experiences to form that bond of strength.

On May 15, 2018, I was released from prison after serving 19 years, one month, and 23 days.

The first day out was a dream. The second day was a little better.

But the persecution did not stop. The parole officer doubled back on calls to the landlord and spooked him concerning my background. Although the parole man knows nothing about me other than some offense from 19 years ago, he forewarned the landlord that I would be trouble for him. For that reason, I was forced to go to a halfway house until a new home plan is approved.

I have approximately 10 more months to serve on my sentence. I have been offered a job by the Abolitionist Law Center, a public interest law firm in Pittsburgh operated by activist lawyers.

I feel better now that I have been home for a few days, but I’m in no rush to piece everything together.

I’m taking it one day at a time and appreciating the partial freedom that I have because some of the people that I left behind are sentenced to death by incarceration.

Our Community Based News Room (CBNR) publishes the stories of people impacted by law and policy. Do you have a story to share? Please contact us at CBNR here.

To support our Community Based News Room, make a donation here.

thanks

[…] Law at the Margins published a piece by Carrington Keys, one of the Dallas 6 group of incarcerated men who were charged with rioting […]